Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, I may receive compensation at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support.

I’ve picked up and set down the cookbook The Joy of Cooking (JoC) by Irma S. Rombauer many times. Why? I was on the hunt for a copy someone used, loved, and cooked from. I wanted to see a few splattered pages and maybe notes jotted in the sidebar.

That didn’t happen.

But, while rummaging through the “bins” of Goodwill in St. Louis, I found one — a 1943 copy of The Joy of Cooking.

While my life wasn’t forever changed, I understand why some people consider certain versions a great resource for classic recipes.

What Is The Joy of Cooking?

The Joy of Cooking is a cookbook compiled by Irma S. Rombauer (October 30, 1877 – October 14, 1962). Published in 1931, The Joy of Cooking: A Compilation of Reliable Recipes with a Casual Culinary Chat became a go-to resource for a variety of dishes.

It [Joy of Cooking] has been said to be one of the three most important cookbooks of the middle 20th century, representing to the rest of the country what “The Settlement House” cookbook was to Central European immigrants and “The Boston Cooking School Cookbook” was to New England cooks.

Many revisions and editions later, The Joy of Cooking remains relevant and popular. You’ll find it in many an American kitchen — and beyond.

Who is Irma S. Rombauer?

Let’s head to St. Louis, Missouri, an interesting, diverse, and unique Midwestern city. St. Louis was the home of the von Starkloff family, a German family who lived in the German part of town. Irma lived with her parents and a sister. She briefly dated Newton Booth Tarkington and had an education befitting the period. In other words, it was with her place in society in mind and not so much a career.

If you haven’t visited St. Louis before, it’s an unusual city because each neighborhood has a different feel to it (for the most part). If you are in Soulard, the first established neighborhood of St. Louis, for example, you’ll discover French-influenced 19th-century architecture.

Walk through the Compton Heights neighborhood. The big, beautiful homes point to 1880s to 1890s construction. You get the idea.

These aren’t locally-used names, either. The neighborhoods plaster their name on signs and paint them over crosswalks. There are 79 neighborhoods in total, according to the City of St. Louis. But on my trip to St. Louis, the Shaw neighborhood was the one I didn’t want to miss — it was the home of Irma S. Rombauer.

Irma S. Rombauer was a woman who not only wrote The Joy of Cooking, but also self-published the first edition of her 135-page cookbook for $3,000. She was self-publishing before it was hip.

If only I’d realized it sooner, I would have tried to seek out the rest of their former family homes.

Why Did Irma S. Rombauer Write The Joy of Cooking?

“There was something in her presence to tell the most discouraged beginner why cooking and joy deserved to be mentioned in the same breath.”

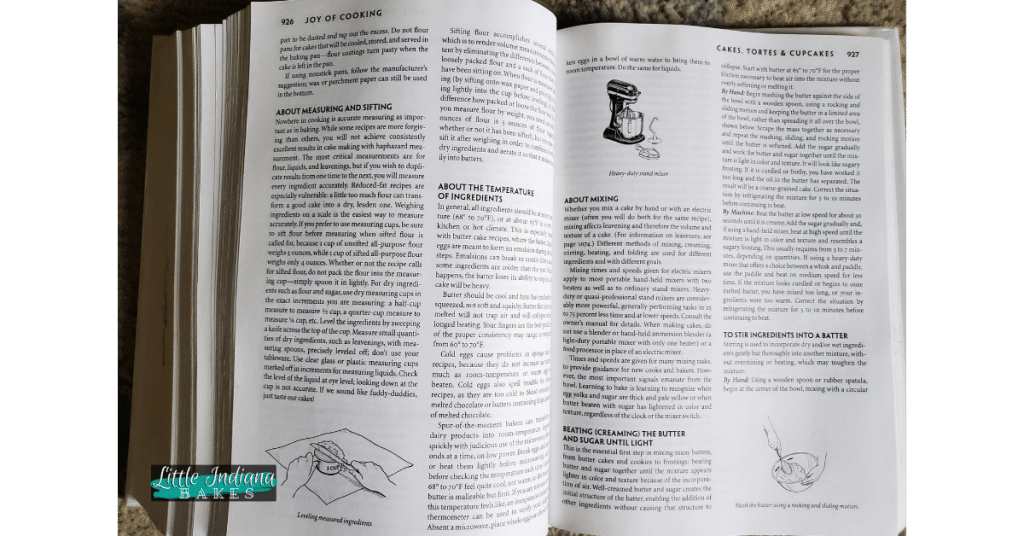

Crack open a copy of Irma’s cookbook, and the interior may mention why Irma started compiling The Joy of Cooking.

The first “Joy,” a modest volume, was published privately in 1931. It was written at the request of my children, who, on leaving home, asked for a record of “what mother used to cook.”

In 1936, The Bobbs-Merrill Company brought out an enlarged and revised edition of my timidly launched maiden effort and this was followed by a second enlarged and revised edition in 1943. A new edition is now before you.

“My roots are Victorian but I have been modernized by life and my children. My book reflects my life and, as you may see by its timely contents, I have not stood still.

Irma wasn’t even a cook.

She had a cook, but she didn’t do the cooking. Her brother Max’s household said it was the “Worst idea I ever heard,” and “Irma’s a TERRIBLE cook,” as shared in Mendelson’s book (page 84, from an interview with Patrician Egan in March 1987).

The idea of Irma S. Rombauer writing a cookbook wasn’t the best in the eyes of her friends and family.

Now, let’s see what Marion, Irma’s daughter, had to say about the creation of JoC.

By 1929 my brother had left home and I was planning to be married and live away, too. My father’s death in early 1930 left Mother, ten years his junior, with the realization that she would soon be entirely without the companionship of an immediate family.

My brother and I had often urged her to put into systematic order the underlying directives of a personal cuisine which had long since excited far more than a neighborhood appreciation. It was at this juncture, partly to comply, chiefly to distract her keen unhappiness, that she decided to spend another summer in Michigan, taking with her, needless to say, the mimeographed sheaf of recipes she had compiled, some eight years before, for the Women’s Alliance.

She knew she needed salvation in work, and that to work she must manage to avoid people, much as she loved and attracted them. And so, on this very different kind of Michigan trip, she went not to Bay View, which she never again revisited, but to a small inn near Charlevoix, where she was a complete stranger.

She had no inkling, of course, that she was carrying with her into Johnny Appleseed country an acorn of even more promising potential, or what world-wide companionship its growth would bring her, what years of absorbing activity.

On her return to St. Louis, Mother persuaded Charlie Maguire’s niece, my father’s former secretary and a friend to all of us, to help her by typing out and commenting critically on her expanding text. By the second summer I was in New York, where manuscript pages from St. Louis arrived regularly.

After painting in the mornings, I tested recipes in the afternoon against the arrival of John, his sister and her fiancé for dinner. The following winter, while I directed the art department at the John Burroughs School in St. Louis, I worked weekends on the chapter headings and the production of the book.

Go back a little more for something closer to the truth:

“At the request of my children, who were leaving home, I began a record of “what Mother used to make.” They thought, correctly, that the work involved would help me tide over a period of loneliness.”

But that’s not the whole truth. It wasn’t only a “period of loneliness.” It was grief.

What Was the Real Reason Irma Wrote The Joy of Cooking?

Edgar Rombauer pursued Irma for a year before proposing marriage. He once told their kids (Marion and Put) what drew him to Irma. The man who described “her beauty, her vivaciousness, and her frankness” and “essentially sunny” disposition, according to Mendelson in “Stand Facing the Stove” (page 39), killed himself and left her with little way to support herself.

On Monday, February 3, 1930, Irma left to go shopping in downtown St. Louis. Edgar loaded one barrel of a Purdey double-barrel shotgun, sat in a chair by an open window, tied a string around his right foot, tied the other end to the trigger, and ended his life.

Although the housekeeper heard the sound, she shrugged it off as a car backfiring. The downstairs neighbors rang when they saw dripping blood from the ceiling.

It wasn’t Edgar’s first bout of depression. He had long had depressive episodes, withdrawing from the world, unable to work or join in the usual social activities of his day. As weeks or months passed, he’d sit in his room and complete crossword puzzles or scrapbooks of world events as family life carried on in the background.

Edgar’s bouts of extreme energy, followed by anxiety and withdrawal, point to manic depression, suggested Mendelson (page 38).

With $6,000 in her bank account, Irma S. Rombauer had to do something.

But what could a woman with few marketable skills and a certain societal position do to help make ends meet? Not much. So, why not compile a cookbook? Irma was one of many women of her time (and status) to try her hand at cookbook writing.

Irma Starts Putting Together The Joy of Cooking

Look at one of Irma’s local competitors, Choice Menus for Luncheons and Dinners, published for a charitable cause by Gladys Taussig Lane. Irma had little regard for the 135-page book, according to Mendelson. It was not for a home cook.

Mr. Rombauer, still a practicing lawyer in Seattle, recalled that ”The Joy of Cooking” was at least partly inspired by annoyance at ”la-di-da” ideas of food.

One day in 1930, his mother called him to complain about a charity cookbook of fancy menus that had just been published by another noted St. Louis hostess, a Mrs. Lang, and was selling for a hefty $5 a copy. Mrs. Rombauer, recently widowed, did not find these meals suitable to Depression-era pocketbooks.

It occurred to her that there might be a market for a cookbook more geared to the ”Zeitgeist,” as she put it, and she had enough faith in the idea to have her collections of recipes published at her own expense.

Irma sourced her recipes in St. Louis and beyond. The granddaughter of one such source remembered the following:

One day, Irma came by to visit, and she said she was writing a cookbook and would Grandma Merkel (Mary Mueller Merkel, a boardinghouse operator and restauranteur with first-hand experience of what it took to survive widowhood) please give her some favorite recipes.

Grandma and Irma talked. Grandma called in Aunt Clara and the three of them talked about what family recipes Irma might find useful.

This was the Depression and people were trying desperately to make enough money to survive. Writing and publishing a book could be costly. One did not dare fail and lose what little assets she had.

When Irma came again, some of the family recipes were ready for her, written out in Aunt Clara’s careful Spencerian hand, in ink, on sheets of paper

. . . .

At the end of the planning, Grandma, despite her encouragement, said, “But, Irma, who will buy your book? All our friends have those those recipes.”

It’s a great story, isn’t it? Marion, however, expressed embarrassment over her mother’s unbridled enthusiasm, writing, “Mother’s hobby is beginning to embarrass me, she carries it to such lengths,” Mendelson’s book shared.

It was a basic cookbook with nutritional suggestions and a unique approach to listing recipes. Irma tried something different — and that experiment paid off.

This was a moment in American history when women were moving far away from their families of origin, following their husbands into growing cities for jobs; the oral tradition of sharing recipes from mother-to-daughter was breaking down, and what had taken over were newspaper columns by home economists and advertisements from food purveyors like meat-packing firms who offered recipes to their readers in impersonal, formulaic ways.

Rombauer’s style represented a major departure from the home economics-driven recipes that looked like nothing more than math problems; her recipes became teaching tools, and following them felt to users as if there was a good friend standing right at their elbow guiding them along in words as well as numbers.

That usability is what made Joy great. From beginning to end — including the index, this book considered its audience.

I think we’ve all experienced the frustration of a shoddy index. That’s not the case with The Joy of Cooking. In fact, it’s something JoC has long prided itself on, thanks to the work of Mary Whyte Hartrich.

Who Was Mary Whyte Hartrich?

All previous editions of “The Joy of Cooking” have been dedicated to my friend Mary Whyte Hartrich, and so is this one.

It is she who from the beginning volunteered to help me with my undertaking and who compiled the admirable index for each edition so well that my readers say, “You can really find what you are looking for!”

In addition she has been an excellent balance wheel for my flights of fancy, advising frequently against too much exuberance and adding a great deal that is valuable to my books.

Who was Mary and how did she get roped into helping out with the cookbook?

However, The Joy of Cooking might never have come to fruition if not for the assistance of Edgar Rombauer’s secretary, Mary (“Maizie”) Whyte Hartrich. Maizie was the niece of one of Edgar’s best friends, and when Maizie’s father died leaving his family’s finances in a wreck, Edgar paid to have Maizie trained as a legal secretary and brought her into his law practice.

After Edgar’s death, Maize volunteered to help Irma with the cookbook project, without pay, and it was Maizie’s series of hand-typed notebooks of The Joy of Cooking that were provided to the A.C. Clayton Company in 1931.

Maize continued to assist with various editions of Joy through 1951, as well as with Irma’s other two cookbooks: Streamlined Cooking (1939) and A Cookbook for Girls and Boys (1946).

A Cookbook for Girls and Boys grew out of a series of articles written for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and even though the book never approached the bestseller status of The Joy of Cooking, it was a respectable entry into the limited field of cookbooks written for children.

It was designed to be a serious instruction manual, not merely a collection of recipes, and is notable for its emphasis on a balanced diet and nutrition. For example, the chapter on vegetables advises that they should be cooked as soon as possible after they are picked, and Irma counsels against over-salting.

The book includes chapters for virtually every category of food, from souffles and timbales, to ice creams and sherbets, as well as providing instructions for how to filet a fish and how to pluck a chicken!

The two-column format of the book is elegant, and features large San-serif type, a simple but helpful use of bold type for the ingredients list, and wide margins, all of which are enhanced by artful chapter heading illustrations from Irma’s daughter, Marion Rombauer Becker.

It was, and is, a family affair.

Is The Joy of Cooking Considered a Good Cookbook?

You either love it or you hate it. Strong opinions accompany mentions of this cookbook in all corners of the internet.

Sometimes I worry a little bit about how the Joy will make itself indispensable in this decluttered new world. Does the Joy…spark joy? I don’t have the patience to polish silver or have an eye for tomato-shaped salt and pepper shakers.

But the Joy of Cooking carries more weight than those things (not just because it’s extremely heavy). It’s not a tchotchke on a shelf but an explosion of knowledge in a tidy container. It’s the ultimate desert island cookbook.

Tidy me to hell, what other cookbook contains both a chocolate mousse recipe, a mezcal explainer, and shredded cheese conversion chart???

And if you’re lucky enough to have one that’s been handed down, then you know it contains much more.

What do I think? I get why it’s a staple in so many kitchens. There’s a smattering of this and a sprinkle of that. The staples are here. But — it’s fun to flip through. Vintage copies contain unique recipes you’ll chuckle over.

What Recipes in The Joy of Cooking Were the Authors’ Favorites?

Write a cookbook and I am guessing it’s guaranteed every interviewer and reader will ask for your favorites. I assume it’s not much different than when interviewers used to ask about my favorite small town.

As you may recall, Nell B. Nichols of Farm Journal cookbooks responded to a question from her granddaughter with a “well, all of them!”

I understand that sentiment. If you’re editing a cookbook, you’re only including your favorites. But there are favorite, favorites too, right? In regards to my small town rambles, I’d respond, “It depends what you’re looking for.” Food-wise?

Well, I love my brownie recipes (or I wouldn’t share them with you), but I love my cakey and frosting-covered brownie recipe just a little bit more.

Fortunately, the authors of JoC made it simple to determine their family favorite recipes.

. . . Finally, in response to many requests from users of “The Joy” who ask, “What are your favorites?” we have added to some of our recipes the word “Cockaigne,” which signified in medieval times “a mythical land of peace and plenty,” and also happens to be the name of our country home.

I wanted to know more about this Cockaigne. Here’s the deal:

While there have been many different versions of Cockaigne appearing in literature throughout the ages, in general, the Land of Cockaigne was a medieval dream world where the regular order things was flipped on its head. In Cockaigne, the poor would be rich, food and sex were freely available, and sloth was treasured and respected above all else.

It was often portrayed as the perfect daydream of the common peasant, a place where the drudgery and struggle of medieval life was nowhere to be seen.

So, what are examples of The Joy of Cooking family favorite recipes?

But her daughter, Marion brought a new perspective to the Joy of Cooking series. She added the term “Cockaigne” to any recipe that was one that the family made in their own home.

Items like Chocolate Chip Cookies Cockaigne and even Cincinnati Chili Cockaigne (which proliferated the myth of chocolate in Cincinnati Chili), started showing up in editions up to 1976, when Marion passed away and passed the biz along to her son Ethan.

What did Irma enjoy doing the most? Her great-grandson John Becker shared that according to his father, Irma’s favorite things to make by far were cookies and cake. Here’s what John had to say about the family’s favorite Joy of Cooking recipes:

First, the “Rombauer Special,” a chocolate cake topped with fluffy white icing. That’s been in the book from the first edition onward.

Irma’s grandmother passed along perhaps the most delicious apple dessert I’ve ever had, “Sour Cream Apple Soufflé Cake Cockaigne.” It’s the quintessential Joy recipe, at least from the family’s perspective—it made the trip from Germany, after all.

“Molasses Thins,” a delicious icebox cookie recipe, is thought to be the last one Irma penned. We find it special for that reason.

Baking cookies and cake? I think we’d get along great.

What Did Reddit Users Cite As Their Favorite Recipes?

If you’re unfamiliar with The Joy of Cooking cookbook, it might help to get an idea of the types of recipes other people consider their favorites. I combed over Reddit posts (and went off on more than one side quest). From banana bread Cockaigne to Irma’s chocolate chip cookies,

But the result is a diverse list of favorite Joy of Cooking reliable recipes.

- The Joy of Cooking Brownies

- Falafel

- Pancakes (and Lemon Pancakes)

- Basil Pesto

- Rich Roll Cookies

- Red Pepper Pasta Sauce

- Sour Cream Muffins

- Butter Cookies

- Sweet and Sour Pork

- hunters chicken / chicken cacciatore (the one with white wine and mushrooms)

- Gazpacho

- Cottage Pie/Shepard’s Pie

- Pasta with Egg & Bacon

- Paprika Chicken

- Coq au vin

- Banana Bread

- Ginger Cake (housewarming 1973)

- Split Pea Soup

- Pecan Pie

- Cloverleaf Rolls

- Chocolate Chip Cookies

Yes, you have your work cut out for you. Pick a recipe. Any recipe. Then get cookin’. Don’t forget to write in your cookbook. List your thoughts, your tweaks, and substitutions.

What Joy of Cooking Edition is Right for You?

There are eight editions that mark genuine stages of the books history, according to Mendelson (xiii preface). These include:

- the original privately-published book (1931)

- the first Bobbs-Merrill edition (1936)

- the best-selling wartime edition (1943)

- the first post-war edition printed from the 1943 plates with minimal changes (1946)

- the first Rombauer-Becker edition (1951)

- the first unauthorized edition (1962)

- the first authorized edition prepared by Marion Becker (1963)

- Marion’s last edition (1975)

Cookbook authors don’t often span generations. But in the case of JoC, it became a family project, handed down from Irma S. Rombauer to her daughter, Marion Rombauer Becker and her husband, John. It then passed to the Becker’s son, Ethan Becker, and then to Ethan’s son, John Becker, and his wife, Megan Scott.

After the first trade edition, published in 1936, there has been a new edition roughly every decade as the family attempted to account for the changing world of available ingredients, kitchen appliances, food safety, and trends.

The 1936 edition, for example, is the only one that devotes a chapter to soufflés and advises on the correct size pan for each cake recipe.

The 1943 edition gave space for wartime rationing.

In 1951, new appliances like blenders and freezers came into the picture and therefore, into the book.

. . .

The fifth edition, first published in 1962 without Marion Rombauer Becker’s permission, had “so many corrections by Marion that the type had to be reset.” It was cleaned up and reissued, and then became the first to be published in paperback as well as to include pâté and Bolognese sauce. It was around this time that “the” in The Joy of Cooking was dropped from the copyright, making it just Joy of Cooking.

Don’t feel overwhelmed by the number of recipes. That’s part of the fun.

The vast number of recipes is the point. It’s the reference book in a collection.

It’s the book you turn to when you need to remember the temperature at which to roast Brussel’s sprouts, or need to whip up a pie for Thanksgiving tomorrow, or just ran over a mountain goat and are wondering if you can eat it.

Pick something you like to eat, and there’s probably a recipe for it in JoC.

Marion took a different track than her mother, Irma. Marion enjoyed nutrition. After decades of dealing with undiagnosed food allergies, Marion found the concept of nutrition intriguing and reflected this interested in her JoC versions.

Having served as the first professional director of the Cincinnati Modern Art Society, Marion brought a modern design perspective to the books that shunned photography and used only line drawings to demonstrate methods.

She also added new recipes utilizing whole grains and introduced Americans to new foods like tofu, jicama, and kiwi.

That’s not all. Marion later had help from her husband, John.

And many don’t know it’s Cincinnati connection and its connection to Bauhaus architecture. When Irma’s daughter Marion Becker took over the cookbook from her mother in 1963, she was living in Cincinnati at her Bauhaus estate in Anderson Township, which the family referred to as Cockaigne, named after a medieval fantasy land.

Her husband, John William Becker, was the foremost Bauhaus architect in Cincinnati, and had built Cockaigne from his designs in 1940. Germany, where the Bauhaus style originated, is celebrating 100 years of Bauhaus design this year.

Becker is also famous for the Rauh-Pulitzer house in Woodlawn that the Cincinnati Preservation Society recently restored back to life.

I had the opportunity to tour it with the CPA shortly after its restoration and can attest that it’s a masterpiece of modern design. Although more known for his architecture, and wild 70s Trumpian combover, Becker also contributed to the Joy cookbook series with his wit and humor.

It began as a self-published work, a way to hopefully earn a little money, and turned into something far more.

The Joy of Cooking was no longer a book by amateur home cooks. It now had a culinary pedigree, though throughout the subsequent years, facsimiles and reprint editions have worked to honor or revisit what made Joy such a gift.

The 2006 75th anniversary edition was based on the book’s most popular 1973 edition and remains popular and beloved today.

Then there’s Marion Rombauer Becker’s last edited book.

The 6th edition was published in 1975 and was the last to be edited by Marion Rombauer Becker, the book’s original illustrator and daughter of its original author, Irma Rombauer. The 6th edition is the bestselling edition of all time.

The “Know Your Ingredients” section was a godsend to those of us who starting cooking in the days before the internet.

The 1997 version, however, is often listed among the least popular versions of the cookbook.

The newest revision has the name of Rombauer scion Ethan Becker on the cover, joining that of his grandmother and his mother, Marion Rombauer Becker, who had nurtured revisions of the book about every 10 years until their deaths in 1962 and 1976, respectively.

But there’s no escaping the fact that for the first time “Joy” belongs not to the Rombauer Becker family but to an outsider, editor Maria Guarnaschelli of Simon & Schuster’s Scribner imprint.

Widely acknowledged to be among the best cookbook editors in America, she is also considered demanding, abusive and so pushy that she pulled Becker aside for an editorial conference on his wedding night.

“Yeah, well, why not?” she says, breaking into hysterical laughter. “Hey, look, this revision waits for no man.”

. . .

“Mom would have liked this book. Mother was not much in the entertainment business, but was more in the knowledge business.

“And while there are a tremendous number of very good personal books out there now–personal and friendly in same sense as Granny–Mother felt the real value was in being an encyclopedic book. She always saw the ‘Joy’s’ place as being more of an American ‘Larousse Gastronomique,’ though a much friendlier version.”

Actually, it will probably have to be both. To sell the number of books Scribner needs to sell (the first printing is 500,000 copies—astronomical for a cookbook), mere information may not be enough. Judging by “Joy’s’ ” history, all of the furor will mean little outside the small world of cookbook writers.

It isn’t as though they changed every recipe. Around 50 recipes were changed. But in the eyes of many … it lost a certain something-something.

Ms. Guarnaschelli’s “All New All Purpose Joy of Cooking,” published in 1997, shrugged off the cozy Midwestern charm of the original work, but it was met with criticism and didn’t sell as well as the original.

. . .

The new version was praised as comprehensive and functional, but it was also called “joyless” by one critic and “corporate” by Molly O’Neill in The Times, and failed to reproduce the sales figures of the original.

The Becker family soon disavowed the book; in 2006, after Ms. Guarnaschelli had moved on to W.W. Norton, Scribner published another revision that restored much of the 1975 edition.

As a former Midwesterner, I can say it’s true — we are big on charm. To cut it out … well, it’s what makes JoC, JoC. Luckily, this cookbook did not end with the 1997 version.

In 2019, Irma S. Rombauer’s great-grandson, John Becker, and his wife, Megan Scott, published an edition of Joy of Cooking, adding over 600 new dishes alongside deep-rooted favorites.

In the process, they began weeding out recipes, like shrimp wiggle, that no longer seemed applicable and adding new ones, like Kao soi gai, that reflect what people eat now. (And there you have 90 years of American culinary history.)

They added recipes from Megan’s family and recipes they had invented themselves. They made sure not to get rid of undisputed classics, like Marion’s banana bread. They revived recipes, like lemony butter wafers, that had been dropped between editions. They also consulted Ethan to make sure they weren’t committing any unforgivable desecrations.

The one they remember especially was Irma’s sauerbraten recipe. “He had memories of it,” Megan says. “We wanted to make it better.” One thing they thought would improve it was including crushed gingersnaps as an optional ingredient, something Irma had been vehemently against. But Ethan was supportive.

“I can’t remember if he ever put his foot down about something,” John says. “If he did, it ended up being not a big deal.”

Think about it though. You have a deadline. You also have a lot of recipes ahead of you. How do you decide what stays and what goes in a book people have Very Strong Opinions About?

JB: . . . We would be testing recipes out of the 2006 edition. We’d make huge weekly grocery trips, all-day affairs, and spend the rest of the time testing 30 to 40 recipes per week.

BP: That’s a long time because what do you have? What is it, 4,600 recipes? I know you use a few freelance testers.

JB: We got to the point where we were a little behind in our testing. A lot of the recipes just needed to have the tires given a good kick, and those we had tested by some friends, including a professional pastry chef, Nora—she even has a chocolate-chip cookie recipe named for her in this edition.

But for the most part it was Ethan and us, often in our Portland kitchen, which is not super-duper tricked out. No Wolf range there!

This time, the family testers were careful about what stayed in the cookbook — and what was safe to remove.

“If we were trying to make room for new stuff, and there was a recipe I had any doubts about, like maybe this was Irma’s favourite? I’d be on the phone to my father to make sure I wasn’t desecrating the family legacy,” says Becker.

Some recipes—like chocolate chip cookies and Irma’s brownies—are standards that people love and have been kept as is. But both are also offered with an update, a fudgier version of the brownie and thicker, chewier version of the cookie.

Expect to see your old favorites and 600 new recipes reflecting the way people cook today.

Do You Want a Copy of The Joy of Cooking with the Squirrel?

Of course, there is one other factor to consider when choosing your Joy of Cooking cookbook: the Squirrel.

Look inside certain editions of JoC and you’ll discover quite the illustration. It’s the skinning process. Back in the late 1990s, my high school boyfriend reached into his basement fridge and thrust a frozen, skinned squirrel in my face. I am still grossed out by the mental image.

But, I can say the illustration of the process in JoC is far less traumatizing (thanks, Adam!). It’s one time I am glad the Rombauer family were against including images.

Do you want the squirrel illustration or not? Here’s how to decide where to begin:

Over the years, in expanding my cookbook collection, I gathered up the other editions I have.

Now, here is where the mystery lies: squirrel is included in 1946 (reprint of the 1943 edition), 1963 (reprint of 1962 with corrections), 1964 (more corrections), 1971, 1975 (fifth revision) and 2006, the 75th Anniversary edition.

But, dear readers, it is not included in the 1997 edition, now titled “The All New All Purpose Joy of Cooking.”

. . .

As Alice said in “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”, it becomes curiouser and curiouser. Sometime between 1997 and 2006, the little squirrel reappears. He is included in the 75th Anniversary edition, published in 2006.

A 1998 publication was a facsimile of the original 1931 edition, so squirrel would have been mentioned in that edition. But, where or where was the little fellow between the 1997 and 2006 editions?

Squirrel? No squirrel? It’s one more decision to weigh when choosing which copy of JoC is the best fit for you.

Why Was The Joy of Cooking a Bestseller?

The books of the day weren’t always so big on personality (except for The Good Earth <3). Have you ever looked at books for kids back then? Not quite the same.

JoC hit the scene in 1931, two years into the Great Depression. What else happened in 1931?

It’s the year TWA Flight 599 crashes and kills University of Notre Dame head football coach Knute Rockne, the Empire State Building is dedicated in New York City, Al Capone is convicted of income tax evasion and sentenced to 11 years in prison, and the Star Spangled Banner became the national anthem.

Other books Americans were buying in 1931 include The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck, Dash Hammett’s The Glass Key and Faulkner’s Sanctuary. The memoir of the Russian Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna, granddaughter of Tsar Alexander II, was also a bestseller.

In other words, books that were popular in 1931 feel very 1931.

The Good Earth is one of my favorite books of all time. Not only do I reread it often (as does my oldest son), but I own (and love) many of Pearl’s other books. But, it does have a certain feel to it. When you consider the rest of the books on that list, it’s true: they are of a different time.

Flip through cookbooks of the day and you notice one thing: they are not big on personality. They lean towards the technical and were not created with regular people in mind. Not always, mind you. But enough so that when a book like Irma’s hit the scene, the mix of useful recipes and delightful commentary set it apart.

I think Irma, with the help of her wonderful biographer Anne Mendelson, will always be remembered as a Lebenskünstler, or “life artist.” What does that mean exactly?

Full of life, precocious, extroverted, the life (or hostess) of the party, an agile mind with a cheerful temperament, strong opinions, fine tastes, and an inability to stay at rest for long.

My father, Ethan, remembers visiting “Granny Rom” at her apartment in St. Louis’s West End, where he was showered with affection, cookies, and cakes—which were by far Irma’s favorite thing to cook . . .

Irma’s gung-ho promotion and lively personality didn’t hurt. Hand-delivered copies made their way into St. Louisans hands and appeared in local shops.

The Indescribable Joy of a Used Joy of Cooking

Found a handwritten letter from Irma Rombauer in a 1943 edition of The Joy of Cooking today…

This find is the stuff dreams are made of:

Wednesday Dear Mrs. Lopez,

For weeks I have been at work with my new cookbook (which is the old “Joy” with a few new frills added.) This took so much of my eye-sight and nervous strength that I could not answer my correspondence.

Thank you so much for your letter about the Texas-fried-chicken. When it came the book was already in page-proof and I could not add it to my collection. It sounds like a wonderful way of preparing chicken and as soon as I have a chance I am going to try it out. Meanwhile many thanks for the recipe and for your interest.

I am so glad you use and like my “Joy”. I love my work but at times it is hard to stick to it as closely as I must. That is when it is wonderful to hear that what I have done is affirmed by others. I hope you are being spared our severe middle-west heat. Today is humid and very close.

All good wishes to you from yours.

Most cordially, Irma S. Rombauer

Now, settle in for a heap of interesting commentary on real people’s JoC thoughts:

And here all my Joy of Cooking (not the 1943 one) book says, written on the inside cover, is a message from my Grandmother.

“If this book is in your house YOU STOLE IT”

stabbytastical,

From The Kitchn readers:

esyl

5 March, 2013

My mom and I both have copies of the ’46 edition. When my mom was living in Algeria in the ’70s, she needed a cookbook whose recipes didn’t include any convenience items, so her mother sent it to her, and it’s the version I grew up with. I still use it all the time and find it full of useful tidbits. What other cookbook will show you how to butcher a squirrel?

I have my mom’s copy of the 1964 edition (although a 1972 printing). It has her notes, as well as mine. I love it both for the recipes I use (peanut butter cookies) and the ones I don’t (boudin noir, possum). I love it most of all because of the stains on so many pages from the early years of parents marriage.

The Kitchen Imp

5 March, 2013

lonisue

5 March, 2013

I have two: 1963 and 1975. The former was a wedding gift in 1964; the latter came with the second husband. 🙂 Still use them as references. And for my coveted hazelnut “toffee,” actually JoC’s “Nut Crunch,” and the oh-so-delicious Vanilla Cream Caramels.

wozlig

5 March, 2013

I cherish my mom’s 1975 copy. The binding is falling apart, so I don’t use it too much for reference anymore, but I always turn to it for certain recipes. It wouldn’t be Christmas without turning to the recipe for Rich Roll Cookies and seeing annotations in my mom’s handwriting. I also have the 7th edition (meh) and the 8th edition (my go-to for basic techniques, etc.)

fumisme

6 March, 2013

I was given a 6th edition (1975) as a high school graduation gift and I have my mom’s 4th edition (1951) which she was given when she married. I cook from the 6th edition but when I want to pick up a cook book just to read, it’s always Joy from 1951!

That list may not help you narrow it down, but it does help you better understand the appeal of this vintage cookbook series.

Where Can You Buy The Joy of Cooking?

Everywhere. Anywhere. Nowhere.

It depends on what you want.

Are you looking for a first edition of The Joy of Cooking, the one Irma published on her own? You and me both. Also, good luck.

In the meantime, you can browse The Joy of Cooking versions for sale below:

Joy of Cooking (1951) by Irma S. Rombauer and Marion Rombauer Becker (Amazon) (eBay)

Joy of Cooking (1952) by Irma S. Rombauer and Marion Rombauer Becker (Amazon) (eBay)

Leave a Reply