Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, I may receive compensation at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support.

In a time when knowing everything about a person is an Internet click away, when every cookbook author has a TV show or “influential” social media status, it’s an odd feeling to realize you know absolutely diddly squat about someone — especially when that someone is as prolific a cookbook editor and author as Nell Beaubien Nichols.

When reading a Farm Journal cookbook recently (they make such good reads), I wondered (yet again) about the Farm Journal Field Food Editor, Nell B. Nichols.

Her name appears in all my vintage Farm Journal cookbooks, yet I didn’t know a thing about her. No author bio appeared at the back of my book, no editor introduction at the front. I decided to dig in and see what I could find about Nell.

She…freelanced stories for magazines based in Chicago and New York City. Over the years, she wrote hundreds of articles for magazines including Ladies Home Journal, Farm and Fireside, The Delineator, Woman’s Home Companion, and Capper’s Farmer.

Her stories came from many sources including university home economics departments, state agricultural extension offices, and food producers’ development labs – but her best sources for insight and flavor were always housewives from farms and cities.

She traveled the nation to sit down in their kitchens and simply shared stories with them. The family recipes and secret tips these women revealed were “worth their weight in prime ribs of beef,” as she put it.

Short version: What an interesting woman. Long story, well, for the long story, you’ll have to stick around awhile.

- Finding Nell Nichols

- Nell Nichol's Early Years

- High School, then a Bachelor's Degree

- Nell B. Nichols Chose Among Master's Programs

- The University of Wisconsin Master's Degree

- Honing her Craft

- Nell's Career Grows

- The Farm Cook and Rule Book

- Woman's Home Companion

- Good Home Cooking Across the USA

- The Farm Journal Magazine

- Cookbooks Become Popular

- Nell Beaubien Nichols Legacy

- Nell B Nichols Cookbooks

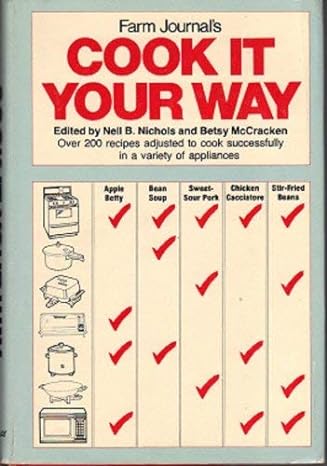

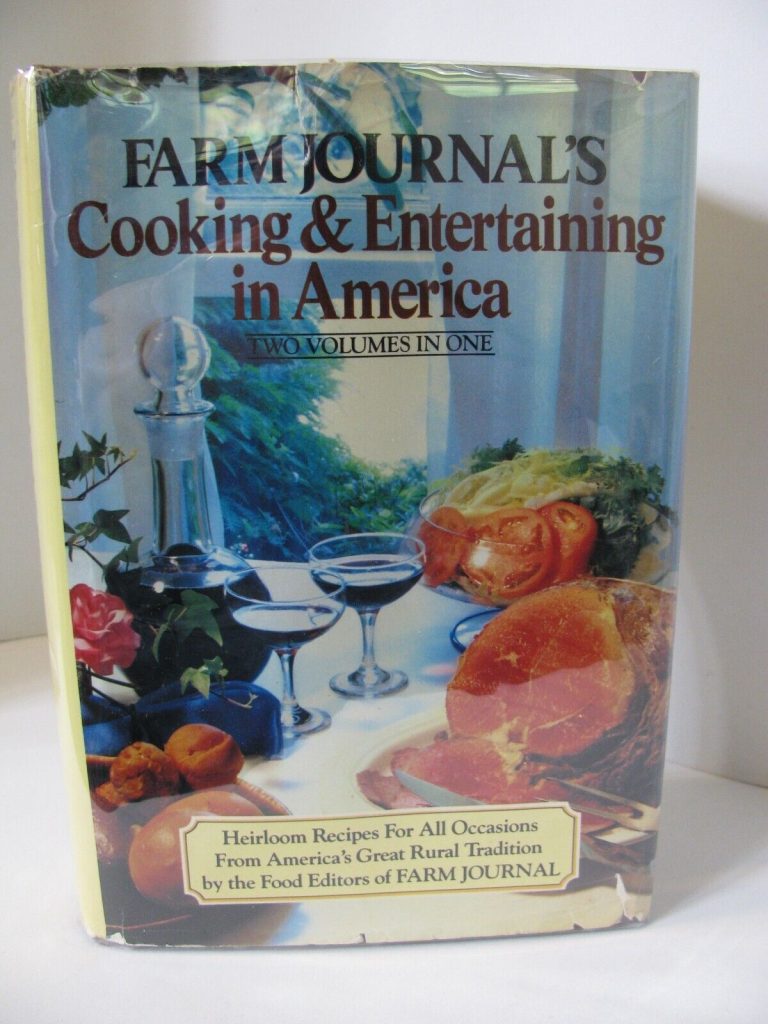

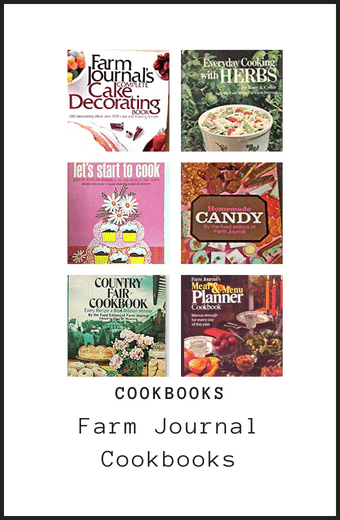

- Farm Journal Cookbooks Edited by Nell B. Nichols

- Related Resources:

Finding Nell Nichols

It wasn’t easy. Hunting for information related to Nell Beaubien Nichols was hard work. For all the wonderful things this wonderful woman was involved in, very little exists about her life. After all, she passed away in 1984, decades before the Internet.

Many of the publications she contributed to have flickered out. Sure, you can find a little info here and there in one of her many cookbook blurbs. But it wasn’t enough.

I wanted to know who Nell Beaubien Nichols was and why her name appeared as “Food Editor” and later as “Food Field Reporter” in so many Farm Journal cookbooks.

Fortunately, I found an interview with Nell when she was 82 years old. It took place in 1978: The University of Wisconsin-Madison Archives Oral History Project, the name of the interviewer is unknown, which is unfortunate, as she did a great job.

The interview is an hour and a half long. I’ve listened, rewound, listened again, repeat, repeat, repeat, and have spent days making sure I got it right.

Now I know. After finding a few other sources online, as referenced and linked appropriately below, as well as combing through vintage magazines, I’m happy to share it with all of you.

Note that unless linked otherwise, common info is all taken from Nell’s voice-recorded 1978 interview since I deem her own words as top authority. I like to think Nell would be tickled.

Nell Nichol’s Early Years

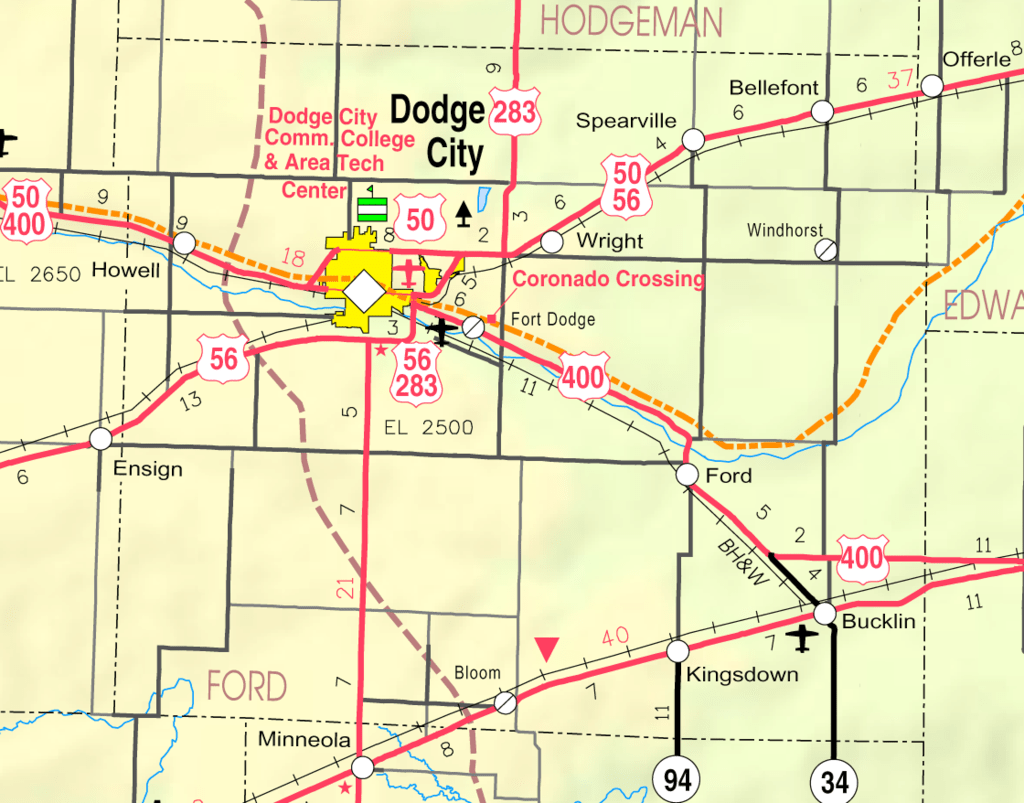

Edith Nell Beaubien Nichols was born in 1895. Nell grew up in Dodge City, Kansas (western Kansas), a cow town, and lived on a ranch.

Nell Beaubien is the granddaughter of Mary C. (Blanchette) Beaubien and was born on the Beaubien Farm south of Maple Hill to Hector F. and Rachel (Curtis) Beaubien. Hector was the son of Edmund A. and Mary C. (Blanchette) Beaubien. Both the Beaubien and Curtis Families were among the earliest arrivals after the opening of land in Maple Hill Township which had previously been a part of the Potawatomi Indian Reservation.

Both families arrived in 1871. Edmund Beaubien had moved west from Illinois in poor health, hoping that the change in climates would prove helpful, but it didn’t. He died in 1874, leaving a large farm to his wife Mary and their two children, Hector and Florence.

The Beaubiens purchased their farm from the family of Jude Bourassa, who was of French and Pottawatomi ancestry and had settled there when his family was removed from Indiana in the early 1840s. The Beaubiens were French and English, but had no Native American ancestry.

They bought the Bourassa’s large log house, but according to Nell Beaubien’s diary, that house burned in the 1880s, and was replaced by a frame house.

The frame house later became the home of the Frank McClelland family and even later their children Don and Hattie (McClelland) Wilson. Mary C. Beaubien moved from the farm into Maple Hill, the year the town was founded (1887) and built a fine hotel directly across the street from the Maple Hill Depot. The lots were contributed to her by the railroad and the Maple Hill Town Company. She lived in and operated the hotel from that time until shortly before her death in 1929.

In Maple Hill News Items, it was reported that railroaders and locals enjoyed fine meals and cooking at the Beaubien Hotel, for the reasonable cost of twenty-five cents in 1887.

In 1911, it noted that Mrs. Beaubien was charging $1.00 per day for meals while caring for two county indigents but the food was still very good and reasonable…Nell Beaubien spent much of her time with her Grandmother Beaubien and eventually helped her at the hotel…

All that time cooking by her mother’s and grandmother’s side wasn’t a chore. It was fun and interesting. But cooking wasn’t necessarily a career choice.

High School, then a Bachelor’s Degree

Nell entered high school where home economics wasn’t an option. It wasn’t offered. Maybe that didn’t matter. Eight-year-old Nell had already decided she wanted to be a newspaper reporter, thanks to a cousin in newspapers in Topeka, Kansas.

So, she took the courses offered, including four years of Latin and three years of German, stating that “geometry was just about my downfall.”

Getting to high school at that time meant riding in a horse and buggy to school five miles away with her two brothers. She saw her first car while in high school. Nell was active and played basketball, wearing black bloomers and a white midi blouse, the standard basketball uniform of the time. There were twelve in her high school graduating class.

Next: College. While college wasn’t an option for women in some families at the time, heading to college was an easy choice for Nell. Her mother had graduated from a normal school, or what they called a teaching-training college back then.

Nell headed to Kansas State College in 1912 where she studied home economics and wanted to minor in journalism. She wasn’t able to get the electives she needed for her journalism minor. She couldn’t even get into a journalism-related class until her senior year, when she snagged two general news writing classes.

This was long before laptops were a common sight. Nell used to rent a typewriter for a dollar a month and peck at it to get her papers done. She was fast, but not accurate, Nell joked in an interview.

Given the distance between Kansas State and her family, and the rigors of travel in the early 1900s, Nell could only head home for Christmas. Thanksgiving was typically spent with the family of a nearby friend.

Nell B. Nichols Chose Among Master’s Programs

Nell graduated from Kansas State College in 1916, engaged at the time to a Topeka man who was influential in guiding her to carry on with home economics. Her teachers were encouraging as well, but her family left her to decide her next step.

She decided to go after a Master’s degree and found herself briefly torn between two schools. She wanted a school with a good reputation in home economics, with an emphasis on nutrition, and journalism. Nell looked to the University of Wisconsin and, to a lesser-extent, the University of Minnesota.

Which one should she choose?

Thanks to a Great Aunt who had visited the ranch when she was a child, she’d heard about “the beauties of Wisconsin, the leaves in the fall, and lake country, and the farming with cranberry bogs.”

With so much research going on with vitamins in the University of Wisconsin labs, it felt like an exciting place.

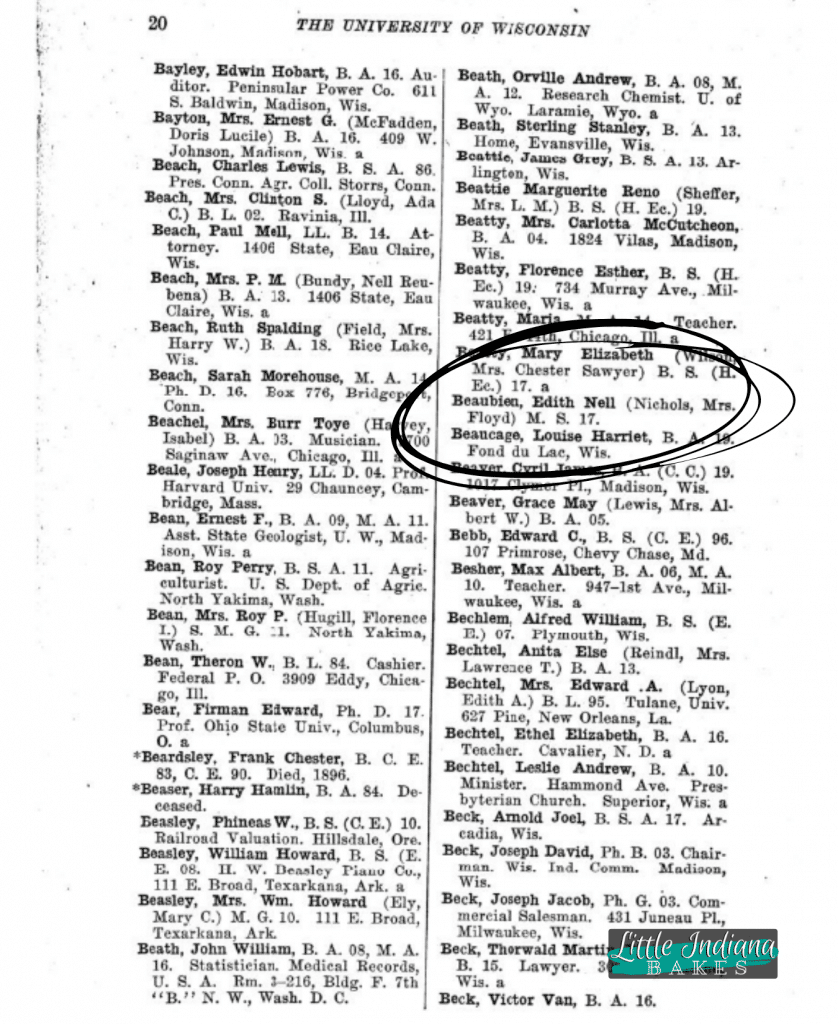

Back then, you couldn’t make a college visit like we do today. Nell had to commit to the school site unseen. Nell was, as she said, “A complete stranger to Wisconsin.” She entered the University of Wisconsin in September of 1916 and majored in nutrition.

The University of Wisconsin Master’s Degree

Girls who studied home economics were not supposed to be interested in writing, mostly in teaching and being a dietician, or getting married and managing their homes. And then journalism, they, the girls, just thought that [journalism] and home economics were pretty dull, because we were interested in science.

Nell B. Nichols, The University of Wisconsin-Madison Archives Oral History Project, 1978.

Making soap was one of the first topics in Nell’s home economics courses. Nell and the other students in her classes worked on an ongoing project to create a book of wartime-friendly recipes. The students developed meatless, wheatless, and sugarless meals to help the war effort.

The recipes, like Steamed Barley Pudding and Corn Muffins, were published by the Women’s Student War Work Council in December 1917.

She raved about her wonderful teachers at the University of Wisconsin, especially Dr. Amy Daniels, Miss Abby Marlatt (director of the department of home economics from 1909 until 1939), Mr. Andrew Hopkins, and Mr. Willard Bleyer, who all guided her along.

As part of Nell’s thesis research, Nell took on the study of soybeans in relation to their potential nutrition for babies — by feeding rats.

Writing her soybean nutrition thesis proved difficult. Nell called her writing “stilted,” as it was such a different style than what she was used to writing. If you’re familiar with Farm Journal cookbooks, you know that Nell’s natural voice is more conversational.

Nell was so stressed about finishing that Dr. Daniels told her to go and sit on the hill overlooking Lake Mendoza to calm down. Nell did. Her thesis was published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry in 1917.

To pass journalism, however, you had to sell a story. “How to Plan Your Meals,” sold to Successful Farming. Then, Nell pointed out, there were seven food groups. Her second story sold to the Milwaukee Journal and dealt with a pedometer and keeping track of steps in terms of common housework.

Who knew that step-tracking was a thing even back then?

Nell graduated and married Floyd Bruce Nichols June 21, 1917 in Lamar, Colorado. He also enlisted in June of 1917. Can you imagine?

Her former professor, Mr. Hopkins, found out and offered Nell a journalism department position to begin August 1 the same year. After Nell’s husband headed off to war, Nell stayed with her family in Colorado, and then returned to Madison, where she had many friends.

She interviewed and wrote about people in the College of Agriculture, and sometimes outside experiment stations, which were then sent to Wisconsin newspapers.

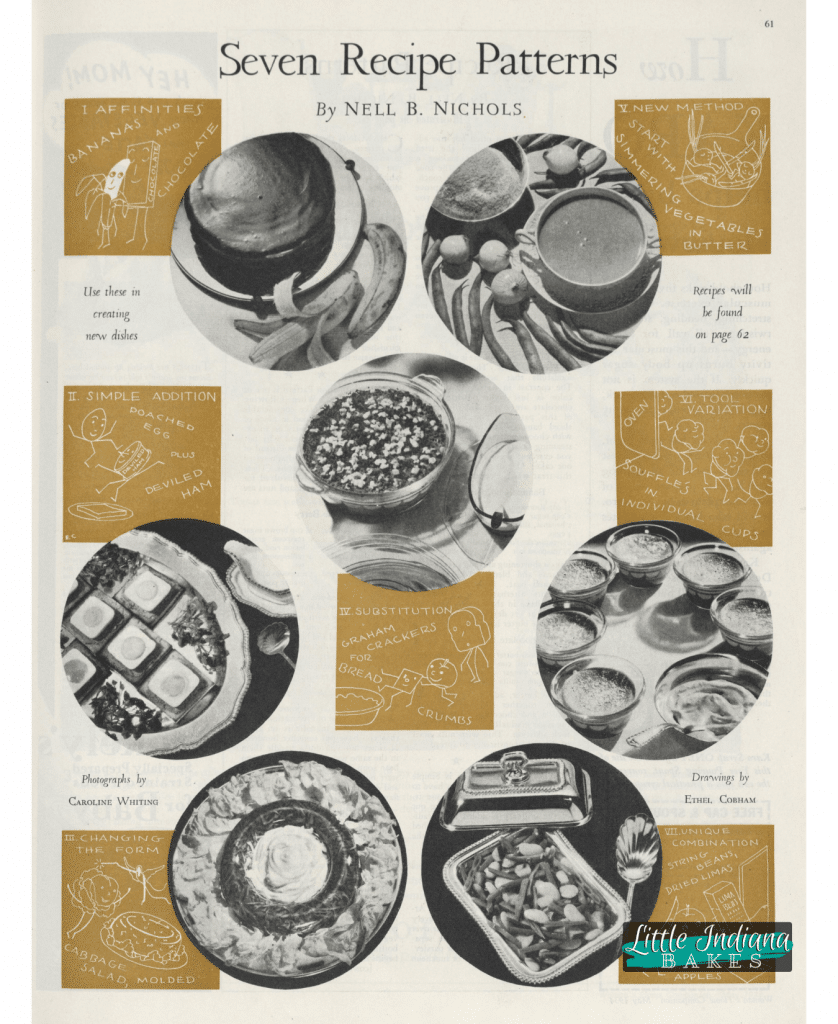

Mr. Hopkins encouraged her to develop a sideline. Whenever she had a little free time, she sent stories to magazines. The editor of The Farm Journal reached out, asking her to make a study of their women’s department.

Little did she know, they would contact her years later, for something much bigger.

Honing her Craft

Nell made $100 a month working for the college. But, she says she made quite a bit more than that since she was selling food stories for $10, $15, or $25 dollars as a freelancer. Nell believed foods didn’t “come into their own” until World War I when nutritional knowledge hit the mainstream.

It was the perfect time to become a food writer, as housewives were clamoring for food information.

So, Nell spent a year working for the college, working from August to August. World War I ended in November 11, 1918, but he was with the army of occupation and didn’t return until September 1919. Her husband headed back to Topeka to see if he could get his former job back.

Floyd had been working for Capper Farm Press since 1913, and “ended up walking into a better one than what he had left,” reminisced Nell. Floyd became a manager and an editor (Illustriana Kansas (1933), by Sara Mullin Baldwin and Robert Morton Baldwin, Page 870).

I didn’t have much idea then that I would ever be writing in magazines, national magazines, but I wanted to.

Nell B. Nichols, The University of Wisconsin-Madison Archives Oral History Project, 1978.

Nell chuckled about how every magazine had some peculiarity of style, but Nell followed what the Home Economic Association set as a standard. She gives the example of “catsup,” as opposed to the correct form, “ketchup.”

Of course, differing layouts meant different types of recipe styling.

Nell preferred listing ingredients first, as it made it easier to “rundown the list.” But, space constrictions sometimes forced paragraph-form recipe styling. Listing the ingredients first makes it easier to “rundown the list,” but space constrictions sometimes forced paragraph-form recipe styling.

Nell’s Career Grows

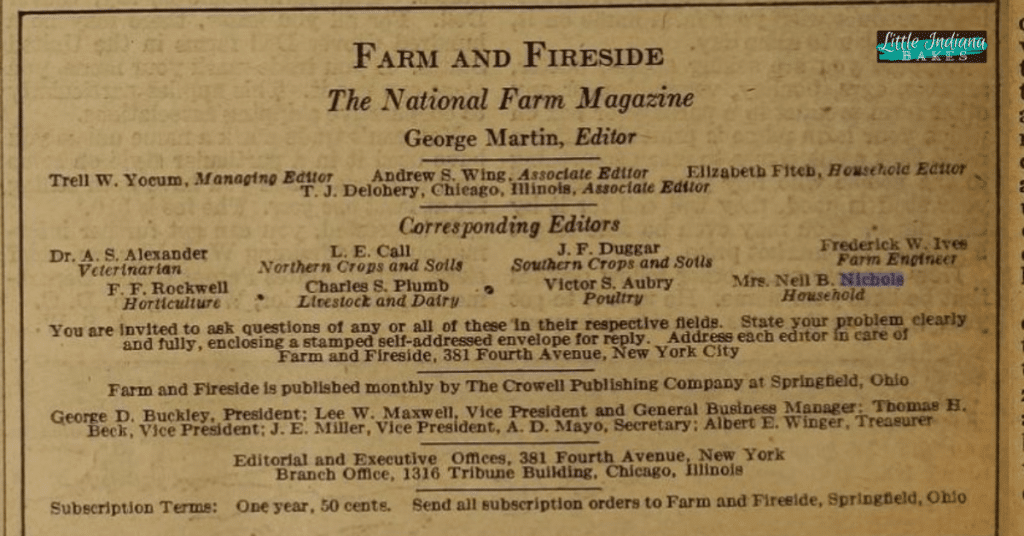

After returning to Topeka, Nell continued freelancing, selling her first story to Ladies’ Home Journal in 1919. It was an article related to the testing of milk for safe human consumption. Farm and Fireside, a national publication, hunted for field editors by reaching out to colleges for recommendations (usually professors).

The University of Wisconsin recommended Nell, so she headed to Chicago to meet the editor, and received the job. Though it didn’t take much time and didn’t particularly excite her, Nell worked from home, writing a mere four food stories a year, at the start, it wasn’t long before she wrote more than that. Plus, it was steady and another clip to add to her growing collection.

Nell’s friend had a job as food editor of The Delineator in 1920, so Nell did several stories for her. In January, 1921, Nell headed to New York, pitching editors for stories.

Many had ties to Wisconsin, which worked out in Nell’s favor. Magazines were searching for new foods and something about them, and wanted people trained in foods — just like Nell.

She wasn’t writing about nutrition, because the magazine editors believed that women weren’t interested in nutrition as a whole. Their thoughts were that women were more concerned with whether something tasted good, than whether or not it was good for them or their families.

But Nell disagreed, sneaking in nutritional information whenever she could.

Nell became a frequent contributor to Midwest magazine Capper Farm Press too, “…a monthly journal circulated widely in the region from Ohio to North Dakota to Texas, and five state farm serving the states of Kansas, Missouri, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Michigan. Collectively they were known as Capper Farm Press,” shares Homer E. Socolofsky in the journal article “The Development of the Capper Farm Press” (Vol. 31, No. 4 (October, 1957), Page 34).

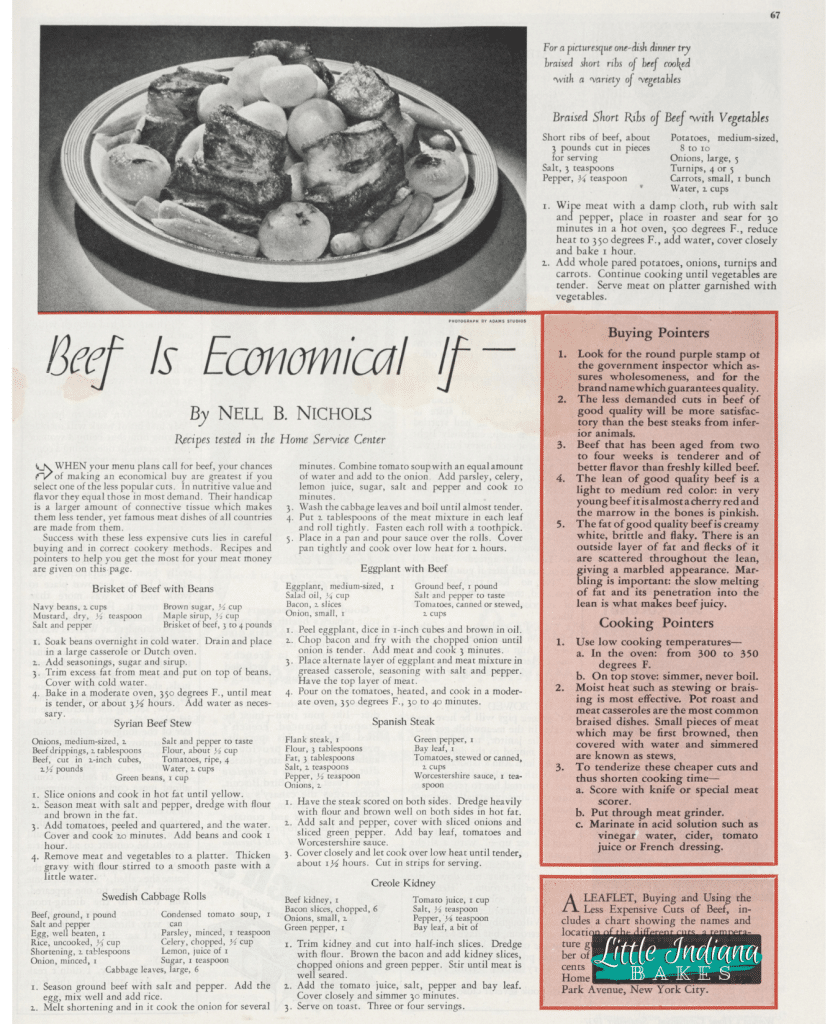

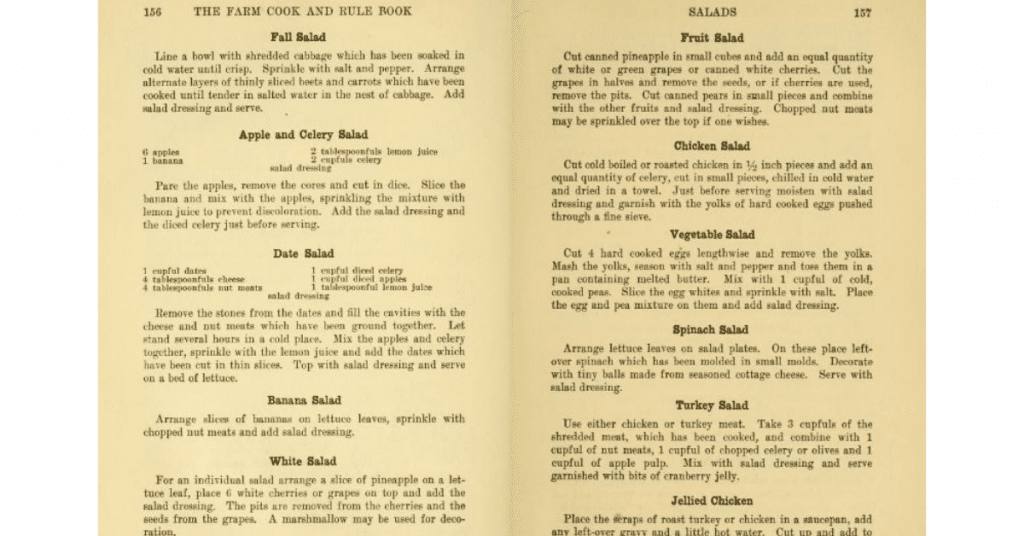

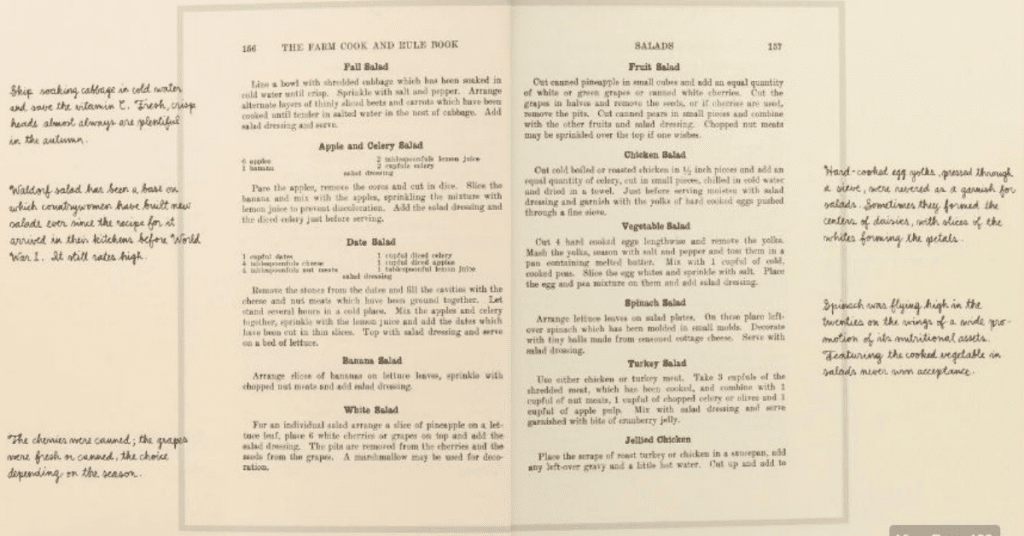

The Farm Cook and Rule Book

While working for Farm and Fireside as well as Capper Farm Press, Nell decided to write a book in 1922. She had already been gathering recipes from farm women in Kansas. She still headed to Wisconsin sometimes, as well as other states, and sometimes received recipes through letters.

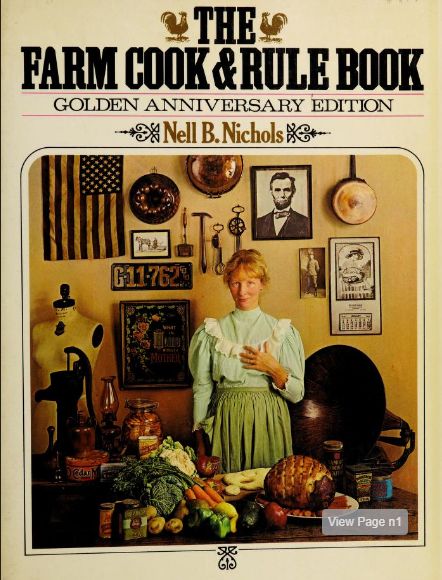

Nell didn’t know where to send her book, The Farm Cook and Rule Book (1923), but she sent it to Macmillan where it was immediately accepted.

Why call it The Farm Cook and Rule Book? “Ninety percent of people were working on a farm,” said Nell’s interviewer (name unknown. Nell definitely had the right target audience and her farming background didn’t hurt.

Nell shared that some people considered the recipes “rules.” She created this cookbook with farm women in mind, since that is who Nell was in contact with.

Nell’s first book remained in print until 1930-1931, however Nell chuckled that the book fast went out of date, due to all the “terrific advances” in food and even things like baking temperatures, appliances, and new products.

Then, there was only butter or lard, so if a recipe called for shortening, the recipe actually meant butter or lard, and usually intended the person to use butter — except in pastry.

Well, now I know to look at old recipes in a different light. They don’t mean shortening shortening at all.

Part 1 of Nell’s first book contains food recipes, while Part 2 is devoted to household recipes, such as starching clothes and laundry soap.

Nell’s grandmothers’ influence appears containing recipes for Grandmother’s Lemonade, Grandmother’s Succotash (a lime bean and corn side dish), Grandma’s Mince Meat, Grandmother’s Eggnog, Grandma’s Floating Island, and Grandmother’s Complexion Clearer (a concoction including fig, raisin, and senna leaf).

Canning and drying food became big during the war, so Nell included instructions for those things too. Nell’s section on “Beauty Secrets,” were the result of interviewing women who were the age Nell was at the time of her interview, included tips for dealing with blackheads and teeth whitening (strawberries are the “secret” here).

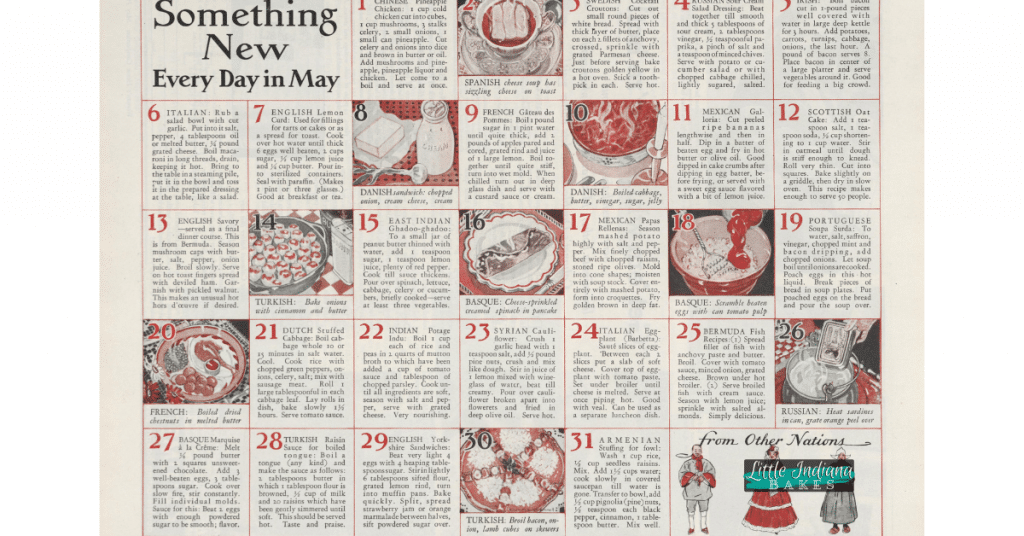

Living in Wisconsin had another benefit: Exposure to ethnic foods. Chinese, Swiss, German, Italian, and French restaurants had opened after a wave of immigration. Nell would drive around Wisconsin and try these different foods — something unavailable in Kansas.

Woman’s Home Companion

In January 1924, Nell wrote a story on laundry, for the Woman’s Home Companion and they received 10,000 inquiries about it. The editor of Farm and Fireside encouraged Nell to reach out to the Woman’s Home Companion to contribute content in 1929.

Nell’s visit didn’t go well.

She stepped in around noon, and spoke with a fashion editor who didn’t have interest in food, so Nell just about stepped right out again. Later, her editor asked how it went. Upon hearing the news, he made a call to Miss Lane (the editor-in-chief), and a receptionist was sent out to get Nell.

Miss Lane questioned Nell about her article ideas. Nell got to around ten when Miss Lane stopped her, and told her she could write for them, from home, as a food field editor.

Although they tried to get her to move to New York, Nell wasn’t having it. Her husband’s job was in Kansas and she didn’t want to live apart from him or her daughter (Mary Jane McCracken “Betsy” born February 25, 1927).

That staff position limited her ability to write for other outlets. Nell had more frequent trips to New York. At first it was once every three months, and then it became closer to monthly visits. These visits planned out her future content.

Nell’s job meant talking to people about what they were doing so she visited often with the University of Madison’s Home Economics department. Nell created lengthy reports sharing what was going on, enabling the magazine to use her report to better plan the magazine content.

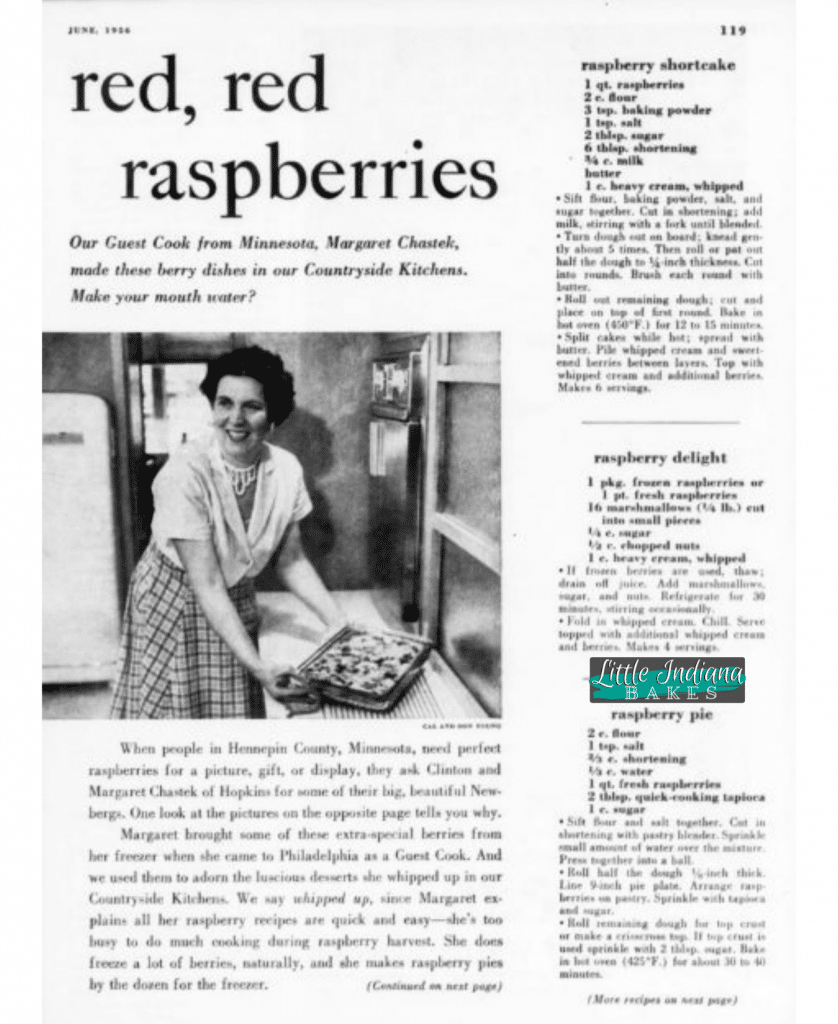

After World War II, Nell was sent around to speak with small groups of homemakers. She would head to a city and have twelve young wives out for lunch. At the lunch, Nell would listen as they spoke of their lives: The shopping, the cooking, their children. She was fascinated.

Nell compiled what she learned. Each month, the magazine published little booklets for home economists in business and for advertisers — just not the general public. These became “The Nell Nichols Report.”

Over three years, Nell traveled to all 49 states (including Hawaii, as Alaska was not yet a state).

Good Home Cooking Across the USA

Nell had far more information than she could possibly use, so wrote another cookbook: Good Home Cooking Across the USA (1952). This book featured foods found at the turn of the half century. It’s a direct result of Nell’s recipe collecting from her travels with Woman’s Home Companion.

While searching for the “best-tasting, most distinctive dishes in the U.S.A.,” Nell divvied the country into parts, thus the regional theme of this cookbook.

I suppose everyone who reaches for Good Home Cooking Across the USA will turn first to the chapter in which the foods of his native state appear. This is a frightening thought. Perhaps some of the delicacies are left out! It may be an oversight.

Certainly no one individual in a lifetime can cover all the communities in this broad land. Nor does everyone in a family or town agree on what tastes good.

Next door neighbors, mothers and daughters, and fathers and sons frequently dispute about which dishes qualify for honors. I have tried to spotlight the ones most praised by hundreds of men and women from Coast to Coast. Indeed, a descriptive title for this report is What People Said.

After a long and successful run, Woman’s Home Companion (1873 to 1957) closed in the beginning of 1957. Based on Nell’s interview, I assume she was let go six months prior to the last issue.

Nell stated that it took six months to find a new job, but that she did in the Spring of 1956 when she joined the staff of The Farm Journal as the Food Editor. The job change meant a move to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

At that time, her daughter, Betsy, had long since graduated from college as a Home Economist herself (1948) and married. Nell’s husband, Floyd, was retired, and he promised to join her there part of the time. Nell wasn’t planning to stay in Philadelphia for too long.

The Farm Journal Magazine

First published in 1877, The Farm Journal magazine began as a one-man show by Quaker Wilmer Atkinson (1840-1920).

“Wilmer Atkinson, a journalist, farmer and Quaker, created the journal as a way to communicate to others who farmed within a day’s journey from Philadelphia. Atkinson was considered a very practical and ethical man, and he was soon labeled a source of solid farming information. As the journal’s reputation spread under Atkinson’s ambitious eye, so also did it’s reach. During Atkinson’s lifetime and in the early 20th century, the magazine achieved national circulation,” according to AgriMarketing.

As a Quaker, Wilmer believed in equal rights and was active in women’s suffrage. Wilmer employed female editors for the more female-specific portions of the magazine. Hey, it was the late 1800s, early 1900s.

Women were the recipe readers and the food fixers, so the magazine spoke directly to them.

“In a time in history that viewed women as less than equal, especially on the farm, Atkinson worked to ensure that they were recognized for their hard work. Even the first issue of Farm Journal, printed in 1877, included a section specifically for women.”

“This issue of Farm Journal asked the women of rural Pennsylvania to send in their favorite recipes and to send in topics that they wished to read about.”

“In a time and place where women likely did not feel important, Farm Journal gave them the chance to feel like a part of something bigger.”

It “…started with Atkinson delivering the publication to farms within a day’s ride of Philadelphia. By 1915 it had more than 1 million subscribers nationwide and by the mid-1950’s topped out near 6 million. As a farm and rural consumer magazine, it included recipes, ag education and rural lifestyle articles. In 1958, Farm Journal shifted its focus back to the farm and to the business of agriculture,” writes Clinton Griffiths in Farm Journal Ag Web.

Nell stayed for four years, making trips across the country for The Farm Journal. At the end of the four year period, Nell was ready to retire.

Farm Journal wasn’t ready to let her go. They wanted her to stay on in a new role as field reporter.

The Farm Journal had a staff called “the family test group,” who were scattered over a good portion of the US. These people would fill out questionnaires. If they discovered something interesting, they would reach out.

Nell also worked with the home economists. She said it was easier then since she had been flying since the 1940s, and it took so much less time. Nell would meet with whomever was scheduled. They’d sit and talk, exchange recipes, and Nell would walk away with a story. Always.

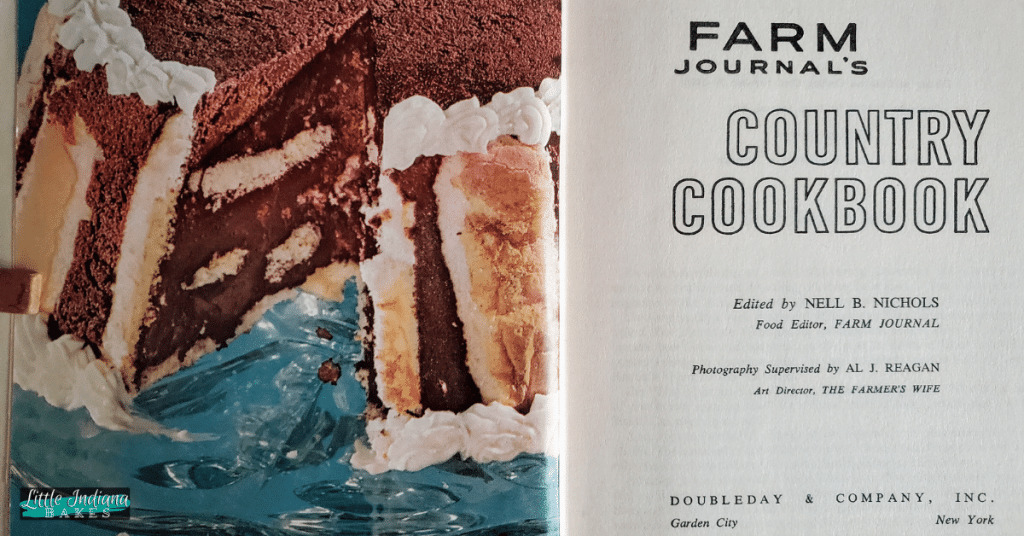

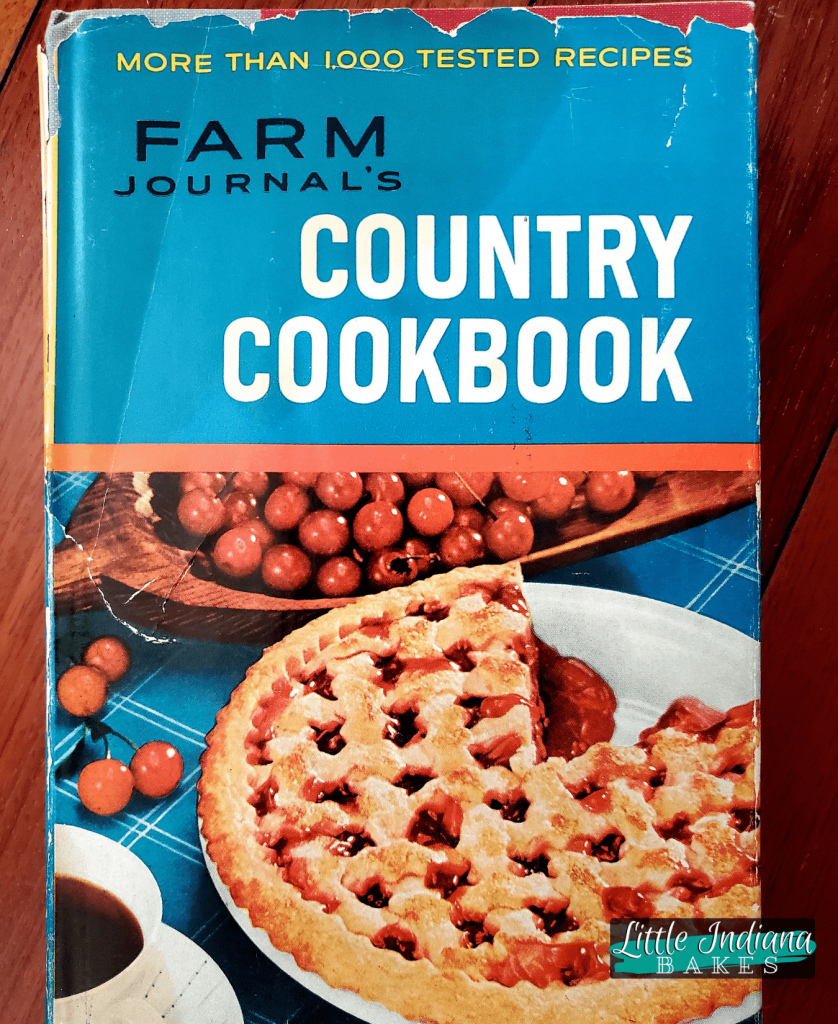

While Nell was at FJ, cookbooks became popular. She edited a cookbook, The Farm Journal’s Country Cookbook that became “very popular.” Nell recalled hearing the news of book sales reaching 100,000 and how she “thought it was very wonderful.”

The book underwent multiple reprints. It is STILL a great cookbook today. The successful book sales kick-started The Farm Journal cookbook business. While Nell did some stories for awhile, her role morphed exclusively into cookbooks.

Cookbooks Become Popular

After time passed, they decided to revise the Country Cookbook. Adding new recipes, subtracting a few older recipes, they created an even larger, more valuable cookbook. Nell’s daughter, the home economist, worked with Nell on multiple cookbook projects.

Mother really was the test kitchen for Farm Journal’s Complete Pie Cookbook and many of the other Farm Journal cookbooks written in the 1960s and ’70s. Grandmother and Mother collaborated for years to find recipes and critically assess them. Mother then tested each recipe and Grandmother wrote them up.

Janet McCracken as interviewed In Behind the Cookbook: Farm Journal’s Complete Pie Cookbook, CKBK, Accessed January 12, 2022.

Cookbooks weren’t so prevalent as they are today. People didn’t have cookbook collections then and didn’t flood the market like they do now.

Nell pointed out (in her 1978 interview) how even magazines have gotten into cookbook production, like Time Life with their Time Life Cookbooks (I have two of them and they are really neat).

Back when Nell was little, she said you made your own cookbook. You would clip out recipes from the newspaper and add it to your own notebook. Over time, you had your own little book of recipes to try.

There is an interest in gourmet cooking and there is an interest in just cooking, plain good cooking.

Nell B. Nichols, The University of Wisconsin-Madison Archives Oral History Project, 1978.

The Farm Journal magazine was the company’s sole source of advertisement. That’s where the cookbooks were marketed. The publisher sold the books in cities too, of course, but The Farm Journal kept their cookbooks right in their target audiences’ eyes.

Geared for girls 12-years-old and younger, Let’s Start to Cook: The ABC’s of Cooking (1966) is full of recipes and advice to help kids get confident in the kitchen.

The guide, How to Bring Up a Good Cook, was meant as an accompaniment for the mother to better help their fledgling cook. Nell realized that many girls maybe didn’t have mothers who knew how to cook, so the guide provides pointers and tips for every recipe, to help the mom know what to do. Nell received notes of appreciation from people all over the US for that one.

Even good things come to an end. Nell retired from Farm Journal October 1, 1977.

Nell Beaubien Nichols Legacy

At the time of Nell’s interview with someone from the University of Wisconsin, Nell shared how she had been working on her autobiography. She was 82 years old and had 100 pages finished.

Nell passed away at the age of 89 on May 28, 1984. Did she finish her manuscript? If so, what happened to it? It’s something I know I would love to read.

Judging from the number of people who cite Nell’s Farm Journal cookbooks as “classics” and “can’t live without,” I don’t think I’m alone in that.

Someone wrote in my cookbook and surely felt the same.

Nell may not have liked the deadlines, but how fortunate we are that she pushed through anyway, taking on numerous deadlines over the years to get her story, her recipes, and her books, out into the world. Nell captured a period in time when food was rapidly changing.

How lucky we are to witness those changes unfolding through the recipe-covered pages of her many fantastic books.

Nell B Nichols Cookbooks

The following cookbooks are the titles Nell wrote separate from The Farm Journal.

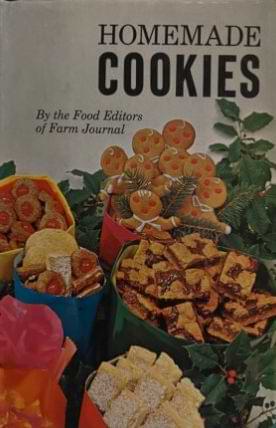

Farm Journal Cookbooks Edited by Nell B. Nichols

Nell wasn’t a young woman when she began writing cookbooks for The Farm Journal. Look at all she accomplished. Wouldn’t you have loved to sit at her kitchen counter and go through her recipes?

Wow! Your post from a couple of weeks ago covering all of the Farm Journal cookbooks had me sifting thru my own collection, and I noticed that my favorites all seemed to be edited by Nell. I wanted to know more about her too, and did a little searching of my own, but you’ve got all the information right here. She’s simply fascinating! Impressive research, and another fantastic post!

Nell’s life was pretty amazing. All those cookbooks and for such a long time. I’m glad you found value in it. 🙂 I love learning about these vintage cookbook authors and am glad to see others do too!

How delighted I am to have found this information on Nell Nichols.

My first Farm Journal book was Homemade Cookies, 1971, which Nell edited. A very plain grey hardcover with red binding, but, the contents! Wow is all I can say.

I also tried to find anything about her as I collected Farm Journal Books. Very little to be found.

Thank you for digging deeper and giving us this grand bio.

What a woman! I pray she is resting in peace for her contributions to our wives, mothers and country.

Thank you so much. I love the Homemade Cookies cookbook! The dust cover is wonderful. Such great colors.