Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, I may receive compensation at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support.

Marion Cunningham shifted food focus back to the home. She encouraged home cooks and provided multiple formats to get her point across in educating the masses.

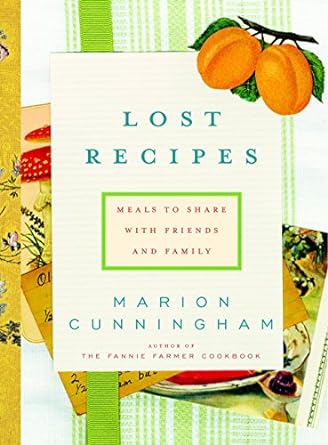

She wrote or collaborated on eight cookbooks, the last of which was “Lost Recipes” in 2003. Her cooking show series “Cunningham & Company” appeared in the early days of the Food Network.

She wrote food columns for the San Francisco Chronicle and the Los Angeles Times, and her articles appeared in most U.S. major food magazines during the past 30 years.

In other words, Marion Cunningham was “all in” when it came to food and education. Those aren’t empty words. Marion Cunningham had her phone number publicly listed in the phone directory.

If anyone had a question, they were welcome to call and ask her.

But Marion wasn’t always a food guide. For many years, while raising two kids, she suffered from alcoholism and agoraphobia, or a crippling fear of leaving her home.

Marion Cunningham

The food that we eat tells us who we are and where we’re from,” she said in 2002. “People have memories that they’ve lived with all their lives of what was fixed at home. How can you do that with a Big Mac?”

Bonnie S. Benwick, Marion Cunningham, Cookbook Writer, Dies at 90, July 11, 2012.

Marion Enwright was born February 11, 1922 in Los Angeles, California to Joseph and Maryann (Spelta) Enwright. Her mother wasn’t in the best of health, described as “frail,” and her father also became an invalid and an alcoholic, shares this SF Gate article.

One of my earliest childhood memories is of our kitchen, where there was always a saucepan of tomato sauce bubbling on the back of the stove. There was also a large, striped can of olive oil sitting by the back door, and a row of garlic heads on the windowsill.

This was an Italian kitchen and it was the room my grandmother lived in. She felt at home sitting at the kitchen table, stringing green beans, shelling peas, chopping garlic or knitting heavy wool socks for my father while she waited until it was time to begin preparing another meal.

Her cure for sadness, bruises or hunger pangs was a piece of bread spread with olive oil or a little of the bubbling tomato sauce. She believed this simple cure would always cheer you up.

When you learn how to make the winter tomato sauce and the summer tomato sauce recipes here, not only will you have something good to put on pasta, string beans, zucchini, hot rice and pizza, but you may also have a cure for some of those troubled moments in life.

Marion’s grandmother sounds like a woman I would have gotten along with well.

Like Marion, I am also 1/4 Italian. My own Italian grandmother’s “spaghetti gravy” (a phrase you’ll hear among Chicago Italians) made everything better.

Even today, I make it when I need a pick-me-up or am feeling nostalgic (always with large meatballs, and with neck bones when I can find them). There’s nothing that quite comes close.

“We used to have meatloaf every Wednesday night when I was growing up. In fact, everyone in our neighborhood in a small town in southern California had meatloaf every Wednesday. And many of us thought it was better than the roast beef we had on Sunday. It was the same way in most of America then, and it was comforting to know just what you were going to have for dinner.”

She didn’t care much for her mother’s cooking.

“My mother followed the government pamphlets on nutrition that she sent away for, and paid no attention to taste,” Marion wrote in an earlier (now pay walled) LA Times article quoted by Laurie Ochoa (‘Fannie Farmer’s’ Marion Cunningham and Her Never-Built Fat Farm, July 12, 2012).

Marion married lawyer Robert Cunningham in 1942. She was 21. They had two children, Catherine and Mark. But Marion didn’t have an easy time.

Mrs. Cunningham insists that if she can follow a recipe anyone can. ”I’m not particularly facile with my hands,” she explained. ”No one will ever write me a letter saying, ‘I don’t know how you ever did this.”’

. . . It was not until after she was married in 1942 to Robert Cunningham, whom she had known since kindergarten, that she started to read cookbooks.

”I had continual failures,” she said. ”I could never get things to come out on time. If it didn’t work I was very determined and I would continue to do it. But I had a few good dishes and people would encourage me.”Mrs. Cunningham was forced to practice on her friends. Her husband, a lawyer who is now retired, has always been an unwilling guinea pig. His tastes run to canned pork and beans, white bread, burned beef and bourbon, she said. ”He doesn’t like homemade bread and he doesn’t like vegetables,” she went on.

”The only green thing he says he likes is money.” Mr. Cunningham concurred in the description.

It must have been frustrating and lonely to spend time cooking and not have your own spouse appreciate what you’ve done. But Marion had other guinea pigs to test on, other than her children.

Their modest income as newlyweds encouraged Cunningham’s family-style approach to menus. “During the five years we lived in Laguna,” she wrote in an article about home entertaining for The Times in 1990, “every friend we knew from our school days arrived to visit (and often to stay).

In order to feed this steady stream, I made casseroles, stews, soups and big hearty salads with thick creamy dressings. All good to eat and cheap to make.” Convenience and frozen foods had already begun to appear on store shelves in the 1940s, “but they weren’t a convenience to me,” she wrote. “I couldn’t afford them.”

At this time, cookbooks were beginning to include recipes making quick meals with convenience foods. It wouldn’t be until the 1950s that convenience foods in cookbooks and sponsored endorsements for such things became common.

Yes, Marion enjoyed cooking. It wasn’t a sunshiny good time. Her husband wasn’t an easy man to live with — he was also an alcoholic.

“One day, I just knew I had to give it up,” she said. . . .

She started swimming. She quit smoking. And she began to venture out of her home and her neighborhood. He husband told her with without a few cocktails, she was no fun.

It would have been hard life for their two kids, dealing with two alcoholics in the home. “Hard” is likely an understatement. I wish I knew more about their lives and how things went for them later. I’d like to think they broke the cycle, but Internet searches led me nowhere. Dead ends.

After the war, the Cunninghams built a house in the San Francisco Bay area suburb of Walnut Creek, where they raised their two children and lived together until Robert died in 1988 after years of failing health. . . .

The clear, blue eyes and inviting manner that defined Marion Cunningham’s public image in later years hardly suggested the difficulties she faced as a young wife and mother.

Through her 30s, she struggled with alcoholism and phobias that made it impossible for her to ride in elevators, airplanes and nearly every other form of transportation.

“I couldn’t even have children until I found a hospital with a maternity ward on the ground floor,” she once said.

Marion’s fear of transportation must have been so hard for her family. Add in the alcoholism and times would have been tough indeed. But somehow, Marion pulled herself together, at least in terms of alcohol. Accounts abound of how much Marion loved a cup of good strong black coffee.

But her life changed in 1972. A friend invited Marion to see James Beard, Marion’s favorite cookbook author.

When she was fifty-one and sober, Cunningham ventured out of California—for the first time in her life—to stay in Gearhart, Oregon, where Beard, her favorite cookbook author, was teaching a cooking course in the resort town of his childhood.

In Gearhart, Cunningham so impressed Beard that he asked her to return the following year as his assistant. “I actually thought he made a mistake and thought I was somebody else, But I certainly wasn’t gonna call his attention to it,” she says.

“Then the classes moved to Fournou’s Ovens in the Stanford Court, and that’s when it all began for me.”

Fournou’s Ovens was in business for 35 years, closing in 2008. In Marion’s time, it was a foothold. She loved to teach others how to cook. That two-week class changed the course of Marion’s life. She had a purpose she couldn’t find before.

The class was a wonderful distraction. For the first time in many years, she felt a sense of power. She felt hope. . .The two began a relationship that rocketed Cunningham into a life she could never have imagined.

She helped him get established teaching at the Stanford Court Hotel on Nob Hill, and she took immediately to the San Francisco cooking scene. Cunningham also drove regularly to Oregon to help him teach, sometimes taking along Chuck Williams, who was getting started with his kitchenware company, Williams-Sonoma.

Although Cunningham didn’t know it at the time, she was helping to nurture the seeds of what would become America’s great food revolution. And she was keeping Beard together.

Marion’s friendship with James Beard led to another unexpected turn in her burgeoning career. He mentioned her name to Judith Jones.

Editor Judith Jones was responsible a decade before for taking The Diary of Anne Frank out of the rejection pile and getting it printed in English — and for publishing Mastering the Art of French Cooking.

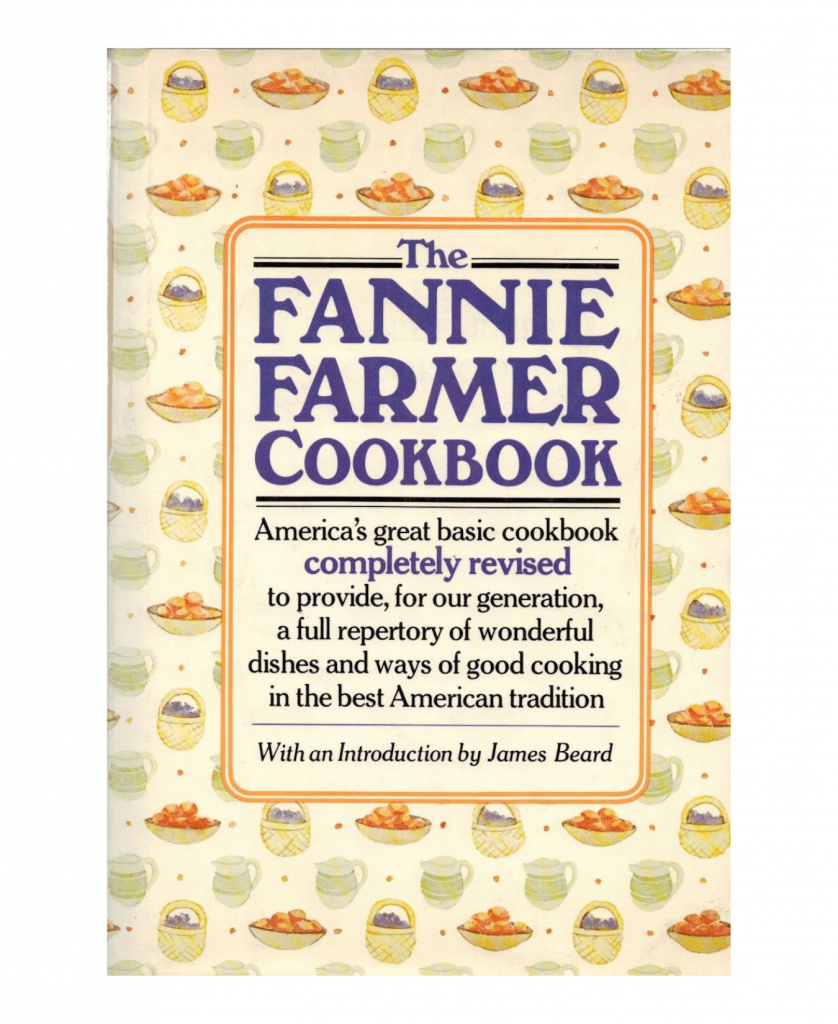

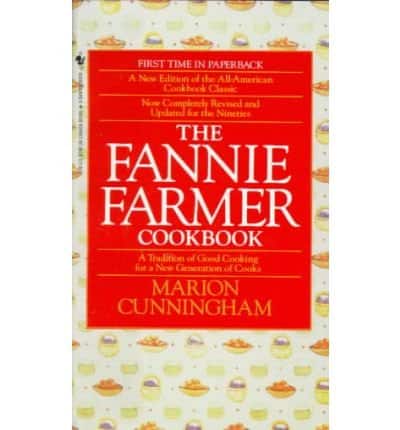

Judith needed someone to revise The Fannie Farmer Cookbook.

Fannie Farmer Cookbook

There is no greater inducement to conversation than sitting around a table and sharing a good meal.

Marion Cunningham, The Breakfast Book (1987), Page xii.

Fannie’s last revision was published in 1914; by the time she died the following year, more than 360,000 copies of the book had been sold. By the sixth edition of 1936, a total of 1,736,000 copies had been printed; the the eighth edition of 1946, that number had reached 2,531,000 copies, shared The Recipe Link.

How has the book changed over the years?

It has always reflected the times. And since times (including family customs, trends in entertaining, and tastes in food) change so rapidly, revisions have been made on an average of every six years. The first edition outlined twelve-course formal dinners and most of the “Family” recipes were designed for groups of six or eight, the average family size at that time.

Later editions offered simplified menus, suggestions for informal entertaining. As modern kitchen equipment appeared, directions for its use were incorporated into the book.

Not everyone agreed with the deliciousness of the recipes inside. Book reviewer Michael Field wrote a scathing review of the 1965 Fanny Farmer edition, the first edition not written by a blood relation to Fannie. In it, Michael pointed out the many flaws.

“Coquille St. Jacques” lacked scallops — and “coquille” is French for scallops, for starters. There were plenty of other errors, from cooking times to ingredients (or lack thereof) to procedure.

Robert H. Fetridge, Jr., the editor of Little, Brown and Co., responsible for the book, wrote a response letter to the editors. Robert tried to downplay any errors, but Michael wasn’t having it. Michael added more detail in his response, with perhaps the best blow of all:

Properly bred Boston ladies over sixty will have nothing to do with any version of Fannie Farmer’s Boston Cooking School Cookbook published after 1928. In fact, they refuse to admit it exists. And, of course, they are right.

As I indicated in my review of April 8th, the only true Fannie Farmer cookbook is the original one.

Michael Fields wasn’t the only person to think the current state of the cookbook was a mess. Let’s look at it another way.

“The heirs of Farmer — who died in 1915, and, though she subscribed to the home-ec lunacies of her era, at least had a good palate — had steadily desecrated the cookbook over the decades, introducing more and more frozen and canned ingredients and adding nasty recipes for gelatin molds and a guacamole made with ketchup,” wrote David Kamp in The United States of Arugula (2006, Page 265).

Fannie Farmer needed an update, if not a complete and total overhaul. The book needed to get back to its roots of good home cooking, while including modern foods, methods, and appliances, to once again become a dependable, trustworthy guide. Judith Jones agreed that Marion would be a good fit. Marion, however, wasn’t convinced. At least, not at first.

Initially, Mrs. Cunningham balked. “I barely made it out of high school,” she had said. “I never paid attention to my teachers. I don’t know where to put periods or commas. How can I do a book?”

James Beard became Marion’s big cheerleader.

Despite his encouragement, Cunningham was plagued by fear of failure. “I kept thinking, ‘If I ever get through this and I’m not humiliated and it’s OK, I’ll be lucky,’ ” she said.

As with any new project that fits your skills, but isn’t exactly what you’ve already done, it takes time to figure out your angle, how to begin, and to find your groove. It can be almost paralyzing, especially undertaking such a task as rewriting a classic cookbook with hundreds of recipes.

If she didn’t do well, Marion could expect to receive the same horrendous reviews as the previous editor.

For almost five years, Marion Cunningham tested and tasted and added in some recipes of her own. When the 12th edition of The Fannie Farmer Cookbook hit the shelves of bookstores everywhere in 1979 — it sold faster than any other version.

When people come up to Marion Cunningham and ask if she is really Fannie Farmer, her deep-blue eyes crinkle as she laughs and replies as kindly as possible, ”Even I am not that old!”

Such a question can easily be excused. Mrs. Cunningham became synonymous with the 87-year-old ”Fannie Farmer Cookbook” five years ago, when her revision of the book sold over 800,000 copies.

A California native who describes herself as a home cook, not a professional, Mrs. Cunningham was the perfect choice to test and update the 1,700 recipes, just as she is for her current project, ”The Fannie Farmer Baking Book.” Both books are accurate reflections of the 61-year-old Mrs. Cunningham’s cooking philosophy.

”Recipes,” she said, ”are the backbone of the average kitchen. This business that if you learn the basic techniques then you can just walk into any kitchen and make a splendid meal – I don’t think that’s true unless you are a professional chef.”

”What’s wrong with a good recipe?” asked Mrs. Cunningham, who is aware that many cooks consider those who use recipes as less than accomplished. ”Some of them say to me, ‘Oh, you’re using a recipe,’ as if I were cheating.”

Marion’s passion became teaching other people how to cook. She wasn’t teaching fancy French food or elaborate gourmet spreads either. Marion focused on real people cooking real things meant to be shared around the family dining table.

Finding Her Niche

Years ago, there was only one way to learn to cook, and that was to watch someone else cook in the kitchen at home. Today, most home kitchens are empty, and people try to learn what cooking they’re interested in from some celebrity chef on television.

But you can’t learn to cook from watching TV; it’s so removed from reality—you never touch the food, never smell the food. Maybe that’s why so many people buy their food already prepared, in boxes or cans or bags—or go out to terribly noisy restaurants where nobody can talk to anybody. Communal events like the family dinner have been sacrificed to individual agendas.

But coming together at the table is a reminder that you are part of something bigger than yourself. You are exposed to your family in a very real way, sitting at a table, facing one another. It’s a metaphor for life. As a platter is passed, you learn to take only what you need and leave enough for others. We were not born civilized; eating together civilizes us.

Somehow, Marion found the time to write articles for several publications. “Always emphasizing the basics and encouraging beginners, she is a regular contributor to Gourmet and Food & Wine Magazine and writes a weekly column for the San Francisco Chronicle and the Los Angeles Times,” reads PBS’ Meet the Chefs of Baking with Julia.

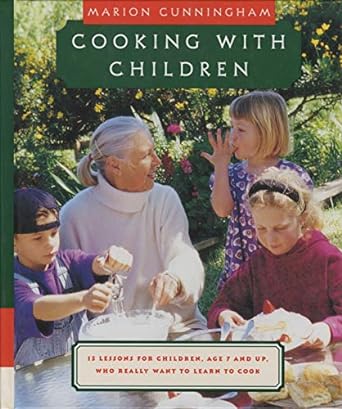

Her approach wasn’t just for adults. Yes, she had adults in mind when she penned Learning to Cook with Marion Cunningham, but she didn’t stop there. She got kids in the kitchen, teaching classes for both adults and for kids.

She created Cooking with Children: 15 Lessons for Children, Age 7 and Up, Who Really Want to Learn to Cook, with clear directions, easy-to-follow directions and just enough recipes to keep a new young cook from feeling overwhelmed.

She even tried to get folks baking again, with The Fannie Farmer Baking Book, another shining example of writing that doesn’t talk down to its novice target.

I’ve mentioned The San Francisco Chronicle cookbook on here before. This cookbook offers a glimpse into the dining scene at the time, why recipes work, and features a slew of popular food chefs of the period.

You get access to Marion Cunningham’s tested recipes. Marion was always testing and testing.

Breakfast, says Marion Cunningham, who has just written a book about it, is the ignored meal. So it is understandable why, during a recent visit to Boston, she made an early morning call at the Four Seasons Hotel — where she had heard the pastries and muffins were splendid — and ordered one of each pastry, muffin and roll on the menu.

In fact, the waiter had to move her to a larger table to accommodate all the plates. Did he find her behavior a bit odd?

It doesn’t matter, replied Cunningham, 65, laughing. “At my age, I can do what I please.”

Then came TV.

Since starting last November, TVFN — as it is known — has now grown to seven hours of programming per day. On May 1, it goes to eight. Eventually it will swell to 12 hours.

“We are the third-largest launch in history — behind TNT and ESPN2,” Mr. Schonfeld says. Once the network gets its foot in the cable door, it is projecting a .3 rating among those subscribers — indicating 36,000 people are watching the show at some point this year. . . .

On May 2, TVFN will include Cunningham & Co. The first show is a paean to James Beard (40 cloves of garlic, please) as cookbook author Marion Cunningham, a Beard student, talks with Judith Jones, Beard’s editor at Knopf publishers. It is a James Beard love feast — more a history of food than anything else.

Marion created more than 70 episodes. It didn’t matter if she was actively writing a cookbook or filming a show, food was never far from Marion’s mind.

While the video above happens to be “Baking with Julia” and not Marion’s show, I love this video anyway.

You can almost feel Julia inwardly cringe and stiffen at the thought of using your finger to push off the extra flour while measuring. Truth is, I have done the same thing. Not often (I keep a butter knife in each plastic container), but I did just do the same thing this morning with granulated sugar.

I suspect most of us home cooks have moments like that.

Marion Cunningham was one of us and she didn’t feel like she had to hide it. I doubt most of us would have had the guts to do such a thing with Julia Child watching.

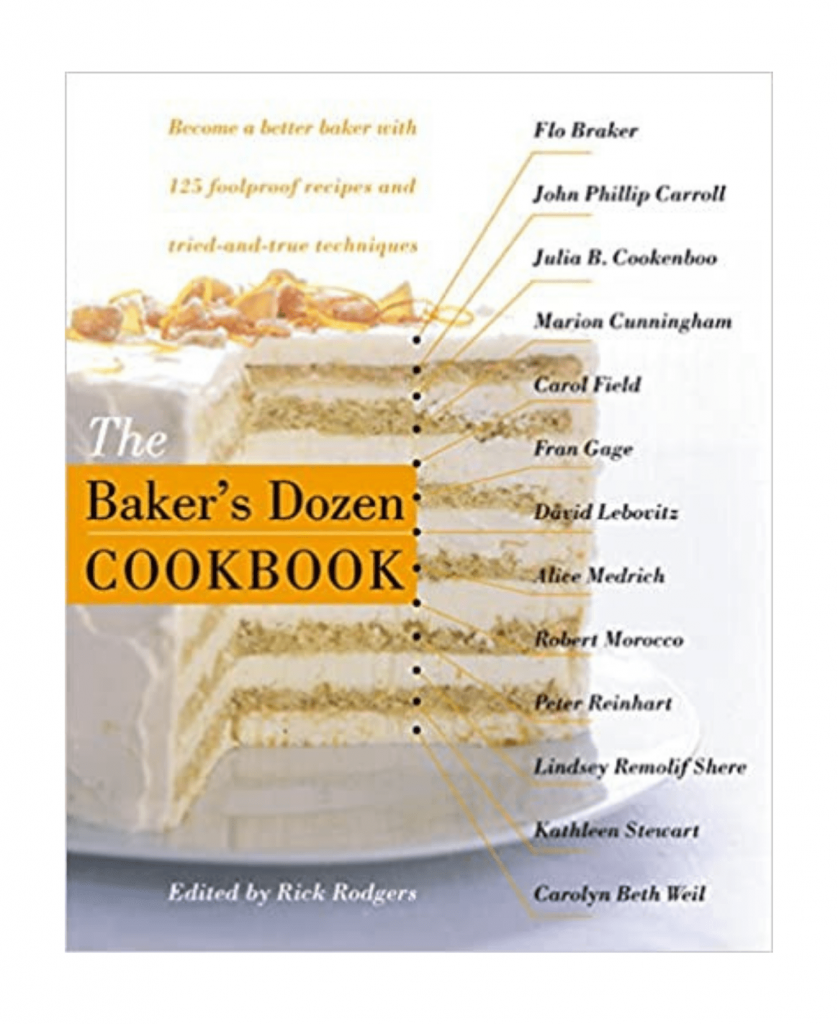

The Baker’s Dozen

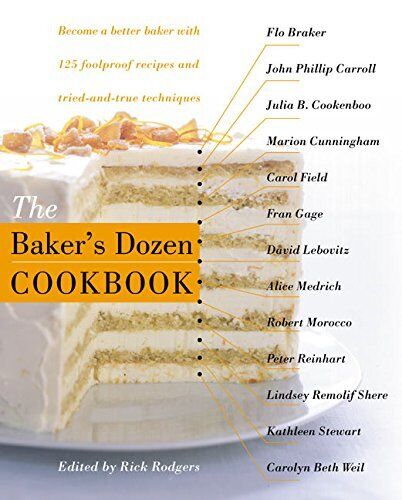

Marion Cunningham and Amy Pressman formed the Bakers Dozen. After their many conversations regarding baking questions, these two consummate bakers brought together a group of interested bakers and created a forum to share knowledge and information.

The first Bakers Dozen meeting was held in San Francisco in 1989.

. . .By 1995 Bakers Dozen had grown to 300 members and began working on a cookbook. Six years of testing and collaborative effort later, The Bakers Dozen Cookbook was published in 2001. The group uses the profits to support local food-related charities.

Can you even imagine? What a wonderful time they must have had sharing recipes and chit-chatting. All of it. No wonder the group grew so fast.

Within a few months, the Bay Area chapter had almost 500 members.

Although we were all pretty much against any kind of structure, like electing leaders and having dues (which had doomed too many well-meaning organizations) she optimistically opened the meetings with a speech, touching on our common mission of sharing knowledge, and she would hold the hundreds of people in attendance with rapt fascination when she took the microphone and introduced topics for discussion.

We all went to work on a book, and at one point, way too many years later, we were all a bit frustrated and overwhelmed by the project. This was mostly due to the fact that during our meetings, instead of getting to the nuts-and-bolts of how to put a book together melding the collective wisdom of 500 members, we’d instead sit around and talk about the best ways to whip egg whites, how to properly measuring brown sugar, and if sifting was indeed really necessary.

We didn’t get much done, much to our editors dismay, but we sure had a great time. That book took almost ten years to complete because we were having too much fun to actually ‘work’.

And because Marion would often keep us entertained with stories of all sorts, most of them were nice (although I liked the other ones best), working was darn near impossible for us.

What a great memory. I’m sure it had its frustrating moments, and working together with a bunch of other professionals could be complicated, especially if everyone has their own “best” way to go about things. But, it would be immensely interesting.

Just Like the Rest of Us

“I don’t like to see food too fancy. You don’t know whether to frame it or eat it.”

Marion Cunningham

Marion was one of us. She loved iceberg lettuce, a food item that made her friend and celebrity chef, Alice Waters, weep. Marion enjoyed the grocery store. Sure, she’d pop into the local farmer’s market, but she liked heading to the store. It wasn’t just for shopping: Marion was spying.

Cunningham — one of the grande dames, along with Edna Lewis and Alice Waters, of American cooking — was imminently practical.

Visiting food journalists who came to profile the beloved cookbook author always marveled at her electric stove and humble kitchen in her family home in Walnut Creek, California.

No Viking stove, no Sub-Zero refrigerator. Her most notable indulgence was keeping two Toastmaster waffle irons on hand. “Nobody wants to wait for waffles,” she said of the redundancy.

In a way, it’s funny. You and I understand the appeal of two waffle makers, right? Anyone who has raised a family or cooked for groups of friends understands. Just like with pancakes, it takes so long to get through making the things.

If you have TWO waffle makers, you are done in half the time — and everyone gets a warm “hot-off-the-press” waffle (as I say in our house).

She loved to go to the supermarket and peer into the baskets of startled strangers, whom she would then interview about their cooking skills. Indeed, she made it her life’s work to champion home cooking and preserve the family supper table, according to Kim Severson (Marion Cunningham, Home Cooking Advocate, Dies at 90, The New York Times, July 11, 2012).

But I do go to the store every day whether I need to or not because I like to see what’s in people’s baskets. I want to see what people buy and how they’re eating.

I’m guilty of being a shopping cart snoop. I am always peering into people’s carts, and even though I sometimes want to tell someone that they don’t need that box of Hamburger Helper and can make pasta themselves in a snap with leftovers for tomorrow — I keep mum.

I’m no Marion Cunningham.

Marion was still writing cookbooks into her eighties.

I spoke by phone with the lively 82-year-old Cunningham, who lives in Walnut Creek, Calif., and asked her what was the “Aha!” moment that inspired her to write this book with her editor of 50 years, Judith Jones.

“It was an idea that I had been thinking about,” she said. “Home cooking has been disappearing, not completely, of course, but because of the obvious more people are working.

“I swim, and there’s a group of young people that swim at my pool and they are living on tight budgets. Cooking at home can save money as well. From talking with them and others, I realized that there is some confusion between home cooking and restaurant cooking. Unlike a restaurant, at home you are trying to relay the ingredients you have on hand into a meal.”

“Food is a topic of conversation,” she continued. “It can be an imprint that you pass onto someone else. It can be a shared experience. Sitting down and eating together is a binding quality for a family. Eating on the run doesn’t cover all the bases it should.”

Time spent around the dinner table is where healthy relationships are formed. It’s when you have a chance to go over the events of the day, to laugh, to reconnect with who should be among the most important people in your life.

Marion learned that lesson and worked hard to pass it on to the rest of us.

Marion Cunningham’s Legacy

Strangers are cooking most of America’s food. Everything is uniform and without a sense of place or history…The microwave is the latest example. There aren’t aromas coming from a microwave. Bit by bit, we have been relinquishing the very essence of what makes a home.

Kim Severson, A Cooking Kinship / Marion Cunningham and Alice Waters on Friendship and Lettuce, May 27, 2001.

People are living like they are in motels. They get fast food and take it home and turn on the TV. Schools and sports groups have soccer practice or what have you during what used to be called the dinner hour.

It’s no wonder Marion Cunningham earned awards for her work. She was involved in so much for so long. Diligent. Persistent.

In 1993, Marion received the Grand Dame award from Les Dames d’Escoffier “in recognition and appreciation of her extraordinary achievement and contribution to the culinary arts.” In 1994, she was named Scholar-in-Residence by the International Association of Culinary Professionals.

Marion Cunningham was awarded the James Beard Award for Lifetime Achievement in 2003.

Cunningham, who turned 81 in February, dismisses the notion of a lifetime achievement award with a smile. “Well, dear,” she said, “I don’t know how they can give it to me for my lifetime. The first 50 years were such a flop.”

Marion Cunningham died on July 11, 2012 in Walnut Creek, California (complications from Alzheimer’s disease).

Since I moved to Paris, I’ve heard from various friends that Marion’s health has declined and she’s unable to work.

Frankly, when she told me about going to her local pool (where she swam daily, until well into her 80’s). On that day, everyone was staring at her and she wondered why…until someone told her that her swimsuit was on backwards, I chalked it up to her just being Marion.

But I guess it was a sign of things to come.

Marion was a multi cookbook author, a syndicated columnist, and teacher with her own television show in a time when not everyone had their own TV show. I will leave you with this useful list of tips Marion provided to her cooking students, as told by one of her students back in 1999.

Author and cooking instructor Marion Cunningham uses the following tips to help new cooks. These “Marion-isms” are based on a list prepared by cooking student Jamie Jobb.

“When cooking, there is one main rule: Taste, taste and taste again.” Problems with a recipe often can be remedied while preparing a dish. It’s much harder, if not impossible, to tweak afterward.

“The oven is our friend.” You don’t need to watch over something if it’s in the oven. Use the time to enjoy your dinner guests.

“With each dish, try to achieve one taste.” Too many ingredients result in a culinary cacophony.

“Your hands remember things because they’re closer to the ingredients.” Don’t be timid about touching the food you cook.

“There are no substitutes, except when you are forced by fate to substitute.” If you do substitute, keep track of what you’re changing so you can replicate the recipe.

“Butter will smooth out sharp tastes and rough edges.” Use butter as a flavor tool.

“No matter what the recipe, things can change.” Slight differences in ingredients, room temperature, humidity, lunar gravitational pulls, solar flares or other unknown conditions can affect how a dish turns out. So always taste as you go and make note of any changes.

“Salt and sugar are instruments of flavor.” They can help marry ingredients in a recipe. They’re usually best used when the dish is cooking, not after.

“Home food is not restaurant food.” You don’t have sous chefs and busboys in your kitchen, so keep it simple.

“Your attitude comes through the food.” If cooking a particular dish is true drudgery, don’t do it. Cook what you like to cook.

Articles by Marion Cunningham

For all the things Marion wrote, I can find so few available to read online. How unfortunate.

Read Marion Cunningham articles online today:

- The Trip of the Iceberg, Saveur, January 23, 2007.

- Biscuits Forever, Saveur, September 6, 2007.

- The Shaker Table, Saveur, October 17, 2007.

Cookbooks by Marion Cunningham

Marion got a late start. She found her passion at 51 and pursued it with a relentless spirit. Yes, she was nervous about leaving her state for the first time, and, later, editing a cookbook — but she DID IT ANYWAY.

Look where it led.

Don’t let fear hold you back either.

Take Marion’s lead. It is never too late.

Cooking with Children: 15 Lessons for Children, Age 7 and Up, Who Really Want to Learn to Cook: A Cookbook (1995) by Marion Cunningham (Amazon) (eBay)

The San Francisco Chronicle Cookbook Volume II (2001) Edited by Michael Bauer and Fran Irwin (Amazon) (eBay)

I’ve enjoyed Marion’s cookbooks for years, but was unaware of her fascinating history! Especially inspired by her late start to her smashing success.