Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, I may receive compensation at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support.

What do you do when you retire in the 1800s? For Pellegrino Artusi (1820-1911), in a movement atypical of men in his day, turned to writing. First, he wrote two books about poetry that didn’t sell much. Then, he turned to cooking.

- “The Gospel of Italian Cooking”

- “The Father of Italian Home Cookery”

- “The Father of Italian Cuisine”

Those are a few of the weighty labels I’ve seen applied to Pellegrino Artusi.

So, who was Pellegrino Artusi? He was a man who, at 71, published his own lengthy cookbook on Italian cuisine: The Science of Cooking and the Art of Eating Well. It’s a book so well known in Italy, it’s referred to as L’Artusi — and he likely didn’t even cook.

To learn about the life of Pellegrino Artusi, and the challenges his project would have faced, it’s important to know a bit about the Italy of his time (although I’m sure his wealth helped smooth over and minimize potential issues).

- Before You Get to Know Pellegrino Artusi, You Need to Know a Little History

- Reliving Italy's Glory Days

- Napoleon Divides the Peninsula into Three

- The Mess of Merging Italy

- Italy's Lack of a Common Language

- Pellegrino Artusi in Forlimpopoli, Italy

- The Artusi's Move to Florence, Italy

- Ugo Foscolo

- Ugo Foscolo's Legacy

- Giuseppe Giusti

- Pellegrino Artusi Writes a Cookbook

- The Scientific Method Applied to Cooking

- Finding the Right Audience

- Death of Pellegrino Artusi

- Casa Artusi in Forlimpopoli

- Is the Science of Cooking and the Art of Eating Well Still Relevant Today?

- Pellegrino Artusi Changed Everything

- Pellegrino Artusi Recipes

- Pellegrino Artusi Cookbooks

- Related Resources:

Before You Get to Know Pellegrino Artusi, You Need to Know a Little History

Loquacity is not satisfied as one ages, it increases as we grow older, as does the desire for good food, sole comfort of the aged.”

Pellegrino Artusi

Italy’s history is complicated. The main thing you need to know is this: before Italy was unified, Southern Italy had problems, like plenty of war, disease (Malaria), and neglect from various ruling parties. Depending on the period in history, the areas that would eventually become Italy were passed along from one royal to another, who may or may not have done diddly squat with the region.

Someone was always plotting war or actively fighting, so moments of peace didn’t last for long. There was a period of wars so heavy that it was named Italian Wars (I didn’t say it was a good name). From 1494 to 1559, these wars made Italy the focal point of European supremacy, involving the big wigs of the day (aka Spain and France).

If people weren’t fighting over control of Italy, then they were passing it around, ignoring, neglecting, or otherwise not trying to do much in the way of improving the lives of the people who lived there. Or, if leaders did try to make a change, they wouldn’t get too far without someone else swooping in and causing a ruckus, and effectively putting an end to any reforms.

Either way, the mainland South fell behind. Giuseppe Garibaldi, the man behind Italy’s unification, wasn’t a hero to everyone.

The financial disparity between Northern and Southern Italy is known as “Italian economic dualism.” It’s an apt description of the jarring divide between the prosperity of Northern Italy compared to the less than stellar conditions of Southern Italy. And it’s nothing new.

Of course, there isn’t a straight answer as to when the shift occurred. Scholars debate whether this difference began in the twelfth century or the seventeenth century, or amid various other events. Either way, for hundreds of years, these two regions have had a significant economic difference that, rather than narrowing in modern times as I would have suspected, the gulf has only widened.

Yes, the difference in lifestyle was still very much apparent even in the 1970s, according to one author.

“To travel from the north to the south in the 1970s was to return centuries into the past . . . many lived in one- and two-room hovels; farmers still threshed grain by hand . . . transportation was provided by donkeys that shared their rocky shelters, alongside a few scrawny chickens and cats.”

Flip back to the not-yet Italy of old, and not everyone was neglectful. At least, not all of the time. People have written entire books on Italy, so please, save the hate mail. In the interest of space and to prevent this article from becoming a small book (too late), I’ve cherry-picked names, dates, and events. For a complete idea of Italy’s struggles, please look for books on Italy at your local library.

Reliving Italy’s Glory Days

Frederick II, King of Sicily and the Holy Roman Emperor, wanted to make his large land holdings resemble the former glory of the Roman Empire. Frederick II was something else.

As well as being a talented statesman, he was also a cultured man, and many of his biographers see in him the precursor of the Renaissance prince. Few other medieval monarchs corresponded with the sages of Judaism and Islam; he also spoke six languages and was fascinated by science, nature and architecture.

He even wrote a scholarly treatise on falconry during one of the long, boring sieges of Faenza, and Dante was right to call him the father of Italian poetry.

When Frederick II wasn’t busy with his poetry, he did get some things done. Frederick II had ideas when it came to his domain. At least, at first.

The kingdom of Sicily was Frederick’s first priority. It had long suffered neglect from his absence and internal strife. The Constitutions of Melfi, or Liber Augustalis, promulgated by Frederick in 1231, was a model of the new legislation developing from the study of Roman and canon law.

The intent of this legislation was to bring together the disparate elements within the kingdom and to unify them more effectively under royal leadership. It provided for improvements in royal administration, greater efficiency in the courts, and a rationalization of civil and criminal procedures in the interests of justice.

Frederick also worked to promote the general welfare of his kingdom. In 1224 he founded the University of Naples. His legislation then dealt with medical education and licensing, public health, and air and water pollution.

For all that Frederick II accomplished, there were plenty of places where he missed the mark. As you’ll see below, Frederick II left a lackluster legacy. He made enemies in high places. Open conflicts between the papacy had Frederick II branded as the precursor to the anti-Christ, an oppressor, or a messiah, with plenty of bloody battles throughout his relatively short life.

Frederick II had believed churches should shrug off their wealth and return to the poor, saintly state as they began, instead of the power-grabbing hubs (and danger to his position) they had become.

Frederick II believed a monarchy had absolute power. Of course, this didn’t sit well with the papacy or other various European powers at the time, who needed the church’s support for political reasons. Northern Italy regions weren’t thrilled with Frederick II’s central control either, chaffing against Frederick II’s rule as the years passed.

When the news of his death was published, all Europe was deeply shaken. Doubts arose that he was really dead; false Fredericks appeared everywhere; in Sicily a legend grew that he had been conveyed to the Aetna volcano; in Germany that he was encapsuled in a mountain and would return as the latter-day emperor to punish the worldly church and peacefully reestablish the Holy Roman Empire.

Yet he was also thought to live on in his heirs. In fact, however, within 22 years after his death, all of them were dead: victims of the battle with the papacy that their father had begun.

Some scholars warn against considering Ferdinand II of the Holy Roman Empire a Renaissance man. While he could be forward-thinking, he managed to turn the Thirty Years’ War (1618-48) from a slew of local scuffles into a major war between two religions (Catholicism and Protestantism), devastating Germany in the process (and starving a population of roughly 8 million).

Ferdinand II wanted his large domain to become Roman Catholic, spurring rebellions in multiple pockets of his holdings.

His actions had consequences. “The ancient notion of a Roman Catholic empire of Europe, headed spiritually by a pope and temporally by an emperor, was permanently abandoned, and the essential structure of modern Europe as a community of sovereign states was established,” according to the Encyclopedia Britannica.

The map of large areas of the world would forever be changed.

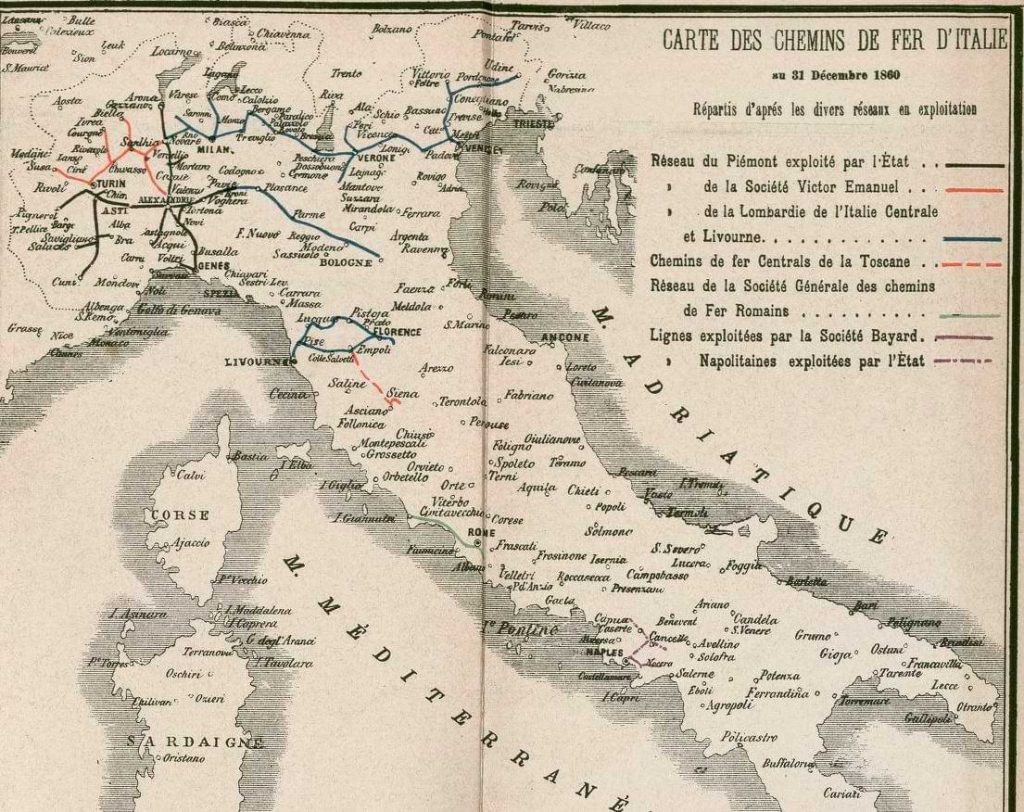

Napoleon Divides the Peninsula into Three

It’s easiest to think of Italy as separate states than a cohesive country. Back then, each of these areas had its own ways of doing everything, beginning with the language they spoke.

There was no sense of identity or a feeling of belonging to a particular region or area. Why would there be, what with divisions and separations occurring throughout Italy’s history? Divisions would happen again when Napoleon hit the scene in 1799.

After Napoleon’s rise to power, the Italian peninsula was once again conquered by the French. Under Napoleon, the peninsula was divided into three entities: the northern parts which were annexed to the French Empire (Piedmont, Liguria, Parma, Piacenza, Tuscany, and Rome), the newly created Kingdom of Italy (Lombardy, Venice, Reggio, Modena, Romagna, and the Marshes) ruled by Napoleon himself, and the Kingdom of Naples, which was first ruled by Napoleon’s brother Joseph Bonaparte, but then passed to Napoleon’s brother-in-law Joachim Murat.

The period of French invasion and occupation was important in many ways. It introduced revolutionary ideas about government and society, resulting in an overthrow of the old established ruling orders and the destruction of the last vestiges of feudalism.

The ideals of freedom and equality were very influential. Also of consequence, the concept of nationalism was introduced, thus sowing the seeds of Italian nationalism throughout most parts of the northern and central Italian peninsula.

With the downfall of Napoleon in 1814 and the redistribution of territory by the Congress of Vienna (1814-15), most of the Italian states were reconstituted: the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia (often referred to as Sardinia), the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the Duchy of Parma, the Papal States, and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (fused together from the old Kingdom of Naples and Kingdom of Sicily). These were largely conservative regimes, presided over by the old social orders.

Various civil societies started to form during the mid-1800s, as Ferdinand II (Ferdinando Carlo) took to the throne. Among these societies were groups dedicated to Italian nationalism and a unified Italy, like Young Italy, an 1831-founded group led by Giuseppe Mazzini.

Ferdinand II belonged to a part of a branch that had ruled Sicily and Naples since 1743, but his reforms wouldn’t “stick.”

Out of the gate, Ferdinand II made a series of liberal reforms. His forward-thinking didn’t last. By the mid-century mark, Italian unification or Risorgimento was widespread, with professional class uprisings. But it wasn’t only the doctors, lawyers, retailers, and other professionals getting involved. Students did too.

January 1848 saw a successful revolution in Palermo, forcing Ferdinand II to uphold a new constitution. Other leaders like Leopold II on February 17, Charles Albert on March 4, and Pope Pius IX on March 14 followed suit.

In the case of Ferdinand II, it only lasted for about four months until his army defeated a portion of the rebel cause (although there is a bit more to the story).

Long story short, the ideas of a unified Italy continued to spread and gain momentum. Ferdinand II (1810-1859), on the other hand, panicked. The few reforms in motion ended, and his response to the fiasco (basically, bombing Sicilian cities) drew the ire of influential Europeans.

Events were leading up to the war of 1859, including Britain’s yearning for a solid Italian ally against the French and the need to undermine too-powerful Austria, which prompted other world leaders to cheer for a joining of Italian states.

During the final years of his life, Ferdinand became more and more isolated from his people and fearful of conspiracies against his life.

The increasingly absolute character of his government denied the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies a role in the Risorgimento (movement for Italian unification) and contributed directly to the easy collapse of the kingdom and its incorporation into Italy in 1860, only shortly after Ferdinand’s death.

Thanks to the war of 1848, control fell to the Italian region of Piedmont, which managed to get Austrians out and bring the majority of Italy under their rule by 1861. This was not an easy time.

Various powers were at play, with different agendas, all trying to rule and make reforms that would benefit whatever they stood for (whether it helped the people of Italy or their interests).

The Mess of Merging Italy

Before unification in 1861, northern Italy consisted of various competing republics and principalities which were integrated in the European economic and political system. The south, which had been unified half a century earlier in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, lay dormant and distant. It resisted national unification on northern terms—and lost.

The imposition of the northern Italian language and northern laws was unpopular. The new central government in Rome made only half-hearted attempts to turn the two parts of the country into a cultural and political whole.

Add in the latifondo system, and you’ve got a bit of a mess. Or, a whole big mess, unless you happen to be a landowner, and then you might just have it made.

As late as the 1940s, land tenure in southern Italy was based on the tradition of the latifondo, or large estate. Such estates practiced an essentially feudal system in which the landowner was entitled to most (as much as 75 percent even after 1945) of the crops raised on his land.

Tenants had no permanent right to the terrain they cultivated, but usually rented, for a fixed period of time, several thin strips of land, often far apart from each other, to which they had to walk every working day.

Not the ideal way to spend your life. Of course, there aren’t only political and economic issues affecting southern Italy. In a word: malaria. Transmitted by mosquitos infected by a teeny-tiny, can’t-be-seen-with-the-human-eye parasite (and there are different species), malaria causes flu-like symptoms (and then some).

When malaria is left untreated, like it would have been back in the day, it leads to severe symptoms, like coma or death, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Although not commonly acknowledged, the widespread presence of malaria in the Italian peninsula during the 19th and 20th centuries is one of the most significant factors in the social and economic development (or lack of it) of the modern country.

An endemic as well as an epidemic disease, it was so enmeshed in Italian rural society that it was widely regarded as the Italian national disease.

Even the word itself – malaria – comes from the Italian mal aria (bad air), as it was originally thought that the disease was caused by a poisoning of the air as wet earth dried out during the heat of summer.

The 1890s weren’t an easy time for Italy. Was there ever an easy time in Italy? Almost half of children born in Italy wouldn’t make it to their fifth birthday (Encyclopedia Britannica). Between malaria, bandits, bad politics, and a host of other reasons, it’s no wonder that people began to leave in search of something better.

When Pellegrino Artusi was finishing up his book and would have been getting ready to publish, the latifondo system caused a slew of uprisings.

Economic hardship and political corruption at home, together with military failure abroad, provoked riots and uprisings throughout the country.

In the early 1890s the fasci siciliani (Sicilian peasant leagues organized by socialists and others) led successful strikes and land occupations until Crispi, in January 1894, used the army to restore order.

The fasci’s leaders were imprisoned, and the movement soon collapsed. At the same time, the government also suppressed an anarchist insurrection in Lunigiana by martial law. Further riots occurred in 1898, mainly in cities and towns, over civil liberties and the high price of bread.

As bad as all that is, there’s more, and it’s another big stumbling block in creating a cohesive country. Italy didn’t have the one thing that most other countries possess: a common language.

Italy’s Lack of a Common Language

“…Italy was created by a small elite at a time when more than 90% of the peninsula’s inhabitants did not speak Italian,” shared an Economist article. Imagine that. There was not a “Google translate” option.

Standard Italian, as a written administrative and literary language, was in existence well before the unification of Italy in the 1860s. However, in terms of spoken language, Italians were slow to adopt the parlance of the new nation-state, identifying much more strongly with their regional dialects.

Emigration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries played an important role in spreading the standard language; many local dialects had no written form, obliging Italians to learn Italian in order to write to their relatives.

The eventual supremacy of the standard language also owes much to the advent of television, which introduced it into almost every home in the country. The extremely rich and, hitherto, resilient tapestry of dialects and foreign languages upon which standard Italian has gradually been superimposed reveals much about Italy’s cultural history.

Not surprisingly, the greatest divergence from standard Italian is found in border areas, in the mountains, and on the islands of Sicily and Sardinia.

You see, Italy only required two years of schooling (made law in 1877). The majority of Italians, some 70% in 1871, couldn’t read at all, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica. Two years of education would hardly make a dent.

Yet decades would pass before Italians shared a common language, and it came from an unexpected source — television. Just how many decades before Italians united in language? Try the 1960s.

“Non é mai troppo tardi” (“It is never too late”) is the name of a television program that aired from 1960 to 1968 with the aim of reducing the illiteracy rate of the Italian post-war population, specifically adults who had not received elementary level diplomas.

This was very common as many Italians did not have either the means or time to send their children to school, much less to themselves return to school.

The show was extremely innovative both in terms of technology and education. It transformed the television screen into an interactive classroom with teacher Alberto Manzi using a white paper backdrop to spell and draw letters, sounds and words.

It would be too little to say that the show was successful – all of Italy would tune in every afternoon before dinner to follow his lessons, either from home or so-called ‘punti di ascolto’ such as local bars, churches, and even schools for those who did not own televisions.

The show finally ended in May 1968, when there was no longer the need to teach from home as both elementary and secondary school attendance had risen, and an estimated 35,000 Italian adults had successfully obtained their elementary level diplomas.

The most influential part of Manzi’s show was its pivotal and unparalleled role in the social and cultural unification of Italians across the peninsula. It started a revolution in communication and the Italian language by bringing education into places where it had never been before: the home.

Personally, I believe that its success lay in its ability to create community through accessibility – there was no discrimination over who could benefit from the lessons and no judgement of individuals who used it as their main source of education. It allowed for the creation and gathering of communities through solidarity, enthusiasm, and a genuine will to learn.

You might get why I shared all the early stuff, but why tell you about something from the 1960s, when Pellegrino Artusi published his cookbook a hundred years before? Easy: so you can get a firm grasp on how many different barriers would have worked against such a project.

Although Artusi’s cookbook contains more recipes from the North (the Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna regions in particular), the areas he knew best, it’s still incredible that Pellegrino included anything else at all given the state of things.

Malaria, lack of a shared language, lack of a sense of nationalism, long-term political oversight or neglect, and illiteracy, all combined to form a very big problem. There isn’t just ONE factor that divided the north and south into such separate states of being. It’s a lot of different things.

Even today, there is a movement to separate Northern Italy from the South. Imagine, then, the regional differences Pellegrino Artusi would have faced while collecting fodder for his book. Traveling would have been downright dangerous.

Now you know a little more about the way things were for Italians, before there was Italy, and in those early years after unification. I highly recommend you take a deeper dive into Italian history for far more information than I can provide here.

Let’s take a look at the life of Pellegrino Artusi now, shall we?

Pellegrino Artusi in Forlimpopoli, Italy

Born August 4, 1820 to Agostino and Teresa Guinchi, Pellegrini Artusi was the only son and named for Saint Peregrine Laziosi (Pellegrino Latiosi) (c. 1260–May 1345), a Catholic Saint nicknamed the “Angel of Good Counsel.”

Sources (even legitimate sources) differ on how many sisters Artusi had, with numbers ranging from six to twelve. Yowza. Regardless of how many members of the Artusi family there were, we at least know they lived in Romagna.

“He went to study in Bologna and then Florence, but never got a degree, and returned home to work in his father’s pharmacy,” Cooking Every Day said.

Life changed for the family forever one winter’s day. Stefano Pelloni (1824-1851), known as “The Ferryman or “Il Passatore,” led his gang (that included a renegade priest) in a terrifying attack at the theater January 25, 1851.

The next section includes traumatic themes. Please bypass the following section, and skip down to The Artusi’s Move to Florence if you are dealing with trauma.

“Halfway through the show, when the curtains lifted, the bandits appeared and the members of the audience were robbed and kidnapped for more than three hours; some were even taken home or were forced to give access to other people’s houses for further robbery,” according to the Bassa Romagna Mia website.

But that wasn’t all. The Pellergino family website has a different side to the story, one that the majority of websites get wrong: the Artusi family wasn’t at the theater that night.

The brigands knew about the family’s wealth, so they forced a family friend, Ruggero Ricci, the son of the lawyer Melchiorre, to get the family to open the door for them. Knocking, and one may imagine, panicking, yelling about how there were wealthy merchants from Rimini, “Sure business!” says the website.

Convinced, Agostino opened the door.

The brigands burst in, attacking those in the immediate vicinity, and stealing items in the process. Rosa and Maria Franca, two of Artusi’s sisters, hid inside a fireplace, concealing themselves. Poor Geltrude Marianna, known to the family as Gertrude, ran into another room, but was caught by the brigands.

After terrible events, she got away, and jumped from the window onto the roof of a different house, later returned by a neighbor “in a deep state of shock.”

On July 16, 1855, Geltrude Marianna was hospitalized in the asylum of Pesaro. She never recovered from the horrible, awful, devasting events, and died there at the age of 49.

Stefano Pelloni died in a firefight on March 23 of the same year, so at least he couldn’t hurt anyone again. Even so, life for the Artusi family would never be the same.

The Artusi’s Move to Florence, Italy

At Artusi’s urging, the family sold the house and shop in May 1851 and moved to Florence via dei Calzaiuoli at the corner with Piazza Della Signoria, on the third floor of the eighteenth-century Palazzo dei Conti Bombicci. His mother, Teresa, died in 1858.

The family moved again, this time to n. 2 of Via dei Cerretani, at Canto alla Paglia, in the former ancient Palazzo de’Marignolli. They lived on the first floor of the large apartment. With two separate entrances, it also served as the site for their new business, at least from what I gather from the family website.

The family starts anew, this time as silk merchants. Pellegrino found a job in Livorno and later founded a bank in Florence. From 1865 to 1870, Florence served as the provisional capital. Sources say that the bank-founding led to great wealth and community respect. Pellegrino’s father, Agostino, passed away in 1861 and was buried in the Basilica of San Miniato al Monte.

Pellegrino Artusi easily lined up spouses for Rosa and Maria Franca (not hard to do when you have a nice dowry), and it sounds like that is when Pellegrino left the business.

Do the math, and he would have been 45. With his own earnings, plus income from the farms of Pieve Sestina di Cesena and Sant’Andrea in Rossano di Forlimpopoli that he owned, Pellegrino was doing just fine.

Try as I did, I cannot find out the name of the bank, what he did, how the farm tied in, or any other details of Artusi’s life at the time before he retired.

I do know that he never married. In fact, he mentions his father’s displeasure at Pellegrino’s lack of a bride in one of his books, according to the site Florence in the World: “my father in the last years of his life seemed to almost hate me because I left him without descendants.”

Without the distractions of a spouse and grandchildren, and an early retirement, you would have plenty of hours in your day to fill with something. And what would be more fulfilling than beginning a large project that can indulge your curiosity, your interest in social works and food, and your, let’s face it, idiosyncrasies?

Now he would do something with all those recipes he had long been collecting.

With everyone married off, Pellegrino Artusi moved to No. 35 Pizazza d’Azegoli square designed by Luigi del Sarto, and named after the writer and politician Massimo d’Azeglio, who died the previous year. Surrounded by 18th and 19th century buildings, it is, by all accounts, a shady and lovely space. It is where Artusi would live out the rest of his days.

Not surprisingly, with its handsome townhouses erected during Florence’s five year period as capital of Italy, it has always been a fashionable address — until the First World War, the garden was gated, London style, and only residents had keys to enter.

Swanky. It sounds like a delightful atmosphere in which to turn your attention towards writing. Artusi first penned two books on popular poets of the day: “Ugo Foscolo” and “Observations as an Appendix on 30 Letters” by Giusti about Giuseppe Giusti.

Ugo Foscolo

Ugo Foscolo (1778-1827) was a poet from Zakynthos, or Zante, an area on the western side of Greece. Zante was under Venetian control from the middle of the 14th century until near the end of the 18th century.

The influences of Venice on Zante, both historically and culturally, aren’t exactly a secret. However, the Treaty of Campo Formio (17 October 1797) ended the Republic of Venice as it was, with its partitioning to France.

Still, Ugo hoped for Napoleon to let Venice go and wrote his poems to match the political debates of the day. Ultime Lettere di Jacopo Ortis (1802; The Last Letters of Jacopo Ortis) centered around a man torn between his love and country.

Five years later, in 1807, Ugo churned out “Dei Sepolcri” or Sepulchres. Mimicking the style of classic Greek and Latin (as a hendecasyllable or a line of eleven syllables) and dedicated to fellow poet Ippolito Pindemonte, Ugo used hendecasyllable form in under 300 lines (295 to be exact).

Please, feel free to hop over to Academia to read the complete translation and accompanying commentary (as well as some of his other notable works). You may read the first 15 lines of Dei Sepolcri below as translated by Ugo:

Beneath the cypress shade, or sculptured urn

By fond tears watered, is the sleep of death

Less heavy? — When for me the sun no more

Shall shine on earth, to bless with genial beams

This beauteous race of beings animate —

When bright with flattering hues the coming hours

No longer dance before me — and I hear

No more, regarded friend, thy dulcet verse,

Nor the sad gentle harmony it breathes —

When mute within my breast the inspiring voice

Of youthful poesy, and love, sole light

To this my wandering life — what guerdon then

For vanished years will be the marble reared

To mark my dust amid the countless throng

Wherewith the Spoiler strews the land and sea?

Ugo Foscolo’s Legacy

Public Domain.

Ugo lived in Venice (1778–1799), Italy (until 1814), and Britain (1814–1827). After writing “Ode to Bonaparte the Liberator” (1797), Foscolo began a life of exile, during which he fought against Austria, first in Venice, then in Romagna, in Genoa, and even in France (1804-1806),” reads Encyclopedia.com.

Ugo experienced great popularity in London for a time. However, financial issues landed him in debtor’s prison. His popularity waned.

According to all accounts, he died in extreme poverty. His work lived on, spurring patriotism and urging those who believed in Italian unification. He had such an effect that 44 years after his death, although he was initially buried at St Nicholas Church, Chiswick, the King of Italy, had Ugo’s final resting place moved in a show of national pride and solidarity.

This time, to the Church of Santa Croce in Florence (the same church highly regarded in his work, Dei Sepolcri) and already entombed with the likes of Michelangelo and Galileo.

Giuseppe Giusti

via Wikimedia Commons.

I don’t know about you, but I don’t tend to think of long ago people as having a sense of humor. I know that’s wrong, but don’t you think of everyone walking around all stony-faced and serious? Anyway, Giuseppe Giusti (1809-1850) was a funny guy or, at least, a funny poet. Artusi’s second book detailed Giusti’s life. Ready for the highlight’s reel?

This guy wrote La Guigliottina a Vapore or The Steam Guillotine (1833). Unlike most satirists of the day, he didn’t stick with the three-line rhyme format or blank verse. Instead, he wrote using different lyrical applications. In Guigliottina a Vapore, he writes about how China came up with a new steam guillotine to make decapitation more efficient for its dictators.

It’s funny in a not-funny way and was a jab at political tyrant Francesco IV of Modena.

“Taken its their entirety, his political satires present a picture of Italy in his day. They are directed against social abuses of many sorts, and at the same time they express a longing for political and moral regeneration.

In view of the frankness and the acritude with which he assailed the grand-ducal government and the Austrians, it is surprising that he escaped the dungeon to which so many other Italian patriots of the time were condemned.,” according to StudyLight.

Giusti’s satirical poems, needling the unemployed spies, the police birri, and the civil servants who were conveniently being retired, belong to this period of political upheaval, when the downfall of the old society was rapidly taking place.

“A Leopoldo II“ (1847; “To Leopold II“) is a poem in which Giusti tried to see that ruler as a true prince and as a father of his region. It was an ephemeral enthusiasm, however, which was soon to be deflated by the Grand Duke’s flight and the demagogues’ seizure of power; when Leopold returned, he was accompanied by the Austrians.Accused of having betrayed the cause of the people, disillusioned and bitter, Giusti at first sought refuge with his family at Pescia and Montecatini, and later at his friend Capponi’s in Florence, where he died on March 31, 1850, of tuberculosis, the silent disease which had been undermining his health all along.

Though deeply saddened by the failure of the Constituent Assembly and the triumph of reactionary forces, Giusti never lost hope for Italy’s resurrection—for her Risorgimento.

You can see why Artusi would like these gutsy men. I barely skimmed the surface. There’s so much more I could have shared (I am completely hooked on their story.)

Alas, Artusi’s books on these two men weren’t well-received and didn’t give him fame or fortune. Artusi turned his attention to something else that had long captivated his interest: food. Good food for the body and the soul.

Pellegrino had long been collecting recipes. Wherever he stayed, he found a way to hang out in the kitchen, watching and taking notes.

Artusi found something to not only occupy his time, but to share his opinions on the healthy way to eat, and his own personal anecdotes along the way. He stepped into the kitchen. Well, sort of.

Pellegrino Artusi Writes a Cookbook

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

See that title? Okay, it’s in Italian, but note that the title is The Science of Cooking and the Art of Eating Well. Remember now, this book isn’t about COOKING well, it’s about EATING well. There’s a reason for that, which we will get to in a moment.

The Science of Cooking wasn’t the first Italian cookbook. After all, Italy in different incantations had been around for centuries. However, it was the first cookbook published after Italy’s unification in 1861. What’s more, Pellegrino Artusi was the first to include recipes in a cookbook from every region after Italy’s unification.

This was a time when complicated and refined French cooking was in style. The king of newly unified Italy, King Vittorio Emanuele II, was a devotee of French food, of butter rather than virgin olive oil. Reflecting this, the cookbooks of the day were written by chefs either trained in France or who wrote in French for other professional cooks.

What made Artusi’s cookbook popular was that its timing was perfect. It was written in Italian when, after unification, Italian, rather than regional dialects, was beginning to be more widely spoken and read among the educated.

It appealed to the new, emerging and affluent middle class represented by the housewives who, assisted by domestic servants, cooked and entertained at home.

Imagine that. Discovering a use for the foods typical to your region. To have a reason to reach for the olive oil that’s abundant where you live, for someone to show you (or, more likely, your cook) other methods of food preparation, because this book? This book was accessible.

The language in which he wrote his celebrated recipe book La scienza incucina e l’arte di mangiar bene puts into everyday Tuscan speech all those expressions which until then, in recipe books and elsewhere, had been expressed by Italianized French words, or indeed directly in French.

19th Century Florence Itineraries: Piazza D’Azeglio, September 27, 2009.

For example, according to the wonderful blog, Luca’s Italy, there was a popular saying floating around Florence at the time about the people of Senia, a city today nicknamed “medieval Manhattan.”

Siena di tre cose tu sei piena: di torri, di campane e di figli di puttane.

Siena of three things you are full of: towers, bells, and sons of bitches.

Pellegrino would have known this saying too. He includes MOST of the phrase in his cookbook, switching out the last bit to jousting. His readers would have been shocked as they began to read and likely would have laughed at the twist at the end. Clever.

The Scientific Method Applied to Cooking

Rice! Behold the fattening food that the Turks feed to their women, so that they will develop, as a celebrated and well-known professor would say, sumptuous adipose cushions.

Pellegrio Artusi, Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well, Page 87.

I believe he would have made a wonderful blogger or food writer, don’t you? But humor can only take you so far. After all, this is a cookbook. So, what about these recipes? Everyone everywhere appears to agree that Pellegrino Artusi likely didn’t help in the cooking.

Yes, as he mentions several times throughout his book, his recipes were tested, even extensively, when the dish proved trickier than expected. Just not by his hand. Perhaps that best explains why he titled his book as he did.

As a fan of the scientific method, Pellegrino Artusi tested his recipes or, you know, he had his cook prepare them. Pellegrino used terms like “q.b.” or “quanto basta” meaning “as needed.” Funny, because that sort of measurement is a running joke in our family. I’ll say to add something until it “looks right” or is “a good amount.”

It is true that Pellegrino’s recipes didn’t possess a Julia Child or Maida Heatter level of measurement accuracy, as he sometimes left them out altogether. But, he is unique in that his regional cookbook gave home cooks direction.

His cook, Francesco Ruffilli, and his housekeeper, Marietta Sabatini, were the muscle here.

Artusi does not tell us he how went about compiling his tome. To complete the manuscript in ten years, he would have had to write fifty entries per year; if he wrote it in five, that would mean one hundred per year or two per week.

Each dish was tested, as he repeatedly insists in the text. He laughs that the reader will think that he is as stubborn as a donkey for trying the recipe for capon poached in a bladder (#367) five times before finally succeeding (well worth the effort, he assures us).

It is widely assumed that Artusi did no cooking himself, but oversaw the work of Francesco and Marietta. But the detailed descriptions of techniques, ingredients, variations and failures suggest that he must have worked with them closely.

As for putting together the manuscript, did he rewrite each draft himself, or did he have an assistant? How did he organize the hundreds of pages? It must have been a prodigious project. This may be why the recipes are numbered. As the collection was assembled the individual items could be reordered and only the numbers changed.

This wasn’t a dry cooking manual. I think we all own enough of those cookbooks, don’t we? While great for technical information, those types of texts are not something you want to sit with and read. Pellegrino’s book was different.

Between the language, humor, scientific method, and recipes, I would imagine that Pellegrino felt confident about his finished book. He dedicated his work to his two felines: Biancani and Sibillone.

And yet, like so many modern-day authors…Pellegrino Artusi couldn’t find a publisher for Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well. Publisher after publisher turned him down, basing their decline on his lack of food-related background, or asked for ridiculous rights Pellegrino wisely rejected, such as passing over 200 lire and the rights to the book.

But, lucky for Pellegrino, he was a wealthy man and paid for his first printing from Florence typographer Salvatore Landi.

As any author would, you give your books away to people and places where it makes sense. Pellegrino handed over two copies to a local lottery. The winners promptly turned them over to a tobacconist.

In the past, a town’s “sali e tabacchi”<sic> license was often given to a poor member of the community so that they could run the shop and earn some money. It was a form of social welfare.

That would have been a bit of a blow. But, Artusi carried on. He just needed to find the right audience, people who enjoyed food and humor. Spoiler alert: he did.

Finding the Right Audience

Do not be alarmed if this dessert looks like some ugly creature such as a giant leech or a shapeless snake after you cook it; you will like the way it tastes.

Pellegrino Artusi, The Science of Cooking and the Art of Eating Well, on Apple Strudel

Image: Public Domain.

So, okay, the tobacco shop may not have been the point of contact for his ideal audience. But, people who would benefit from the book were out there. Pellegrino just needed to spread the word.

For his first edition, Pellegrino had 1,000 copies printed by Salvadore Landi. In 1895, he added 1,000 more, then 2,000 more in 1897, and 3,000 more in 1899 and 1900, according to Gastromimix (translated to English).

Florentine publisher R. Bemporad & Figlio began national distribution, leading to a significant uptick in popularity (and sales). In 1902, Pellegrino included a note thanking R. Bemporad for the hard work spent in promoting the book.

First published in 1891, Pellegrino Artusi’s La scienza in cucina e l’arte di mangier bene has come to be recognized as the most significant Italian cookbook of modern times. It was reprinted thirteen times and had sold more than 52,000 copies in the years before Artusi’s death in 1910, with the number of recipes growing from 475 to 790.

And while this figure has not changed, the book has consistently remained in print.

Pellegrino Artusi, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

But this cookbook wasn’t some stagnant thing, unchanging from edition to edition. It was a never-ending work-in-progress. People sent in letters, with recipes, featuring foods they felt needed inclusion, or to share a different version.

That’s part of how Pellegrino’s audience grew. When people get to be a part of something, when they feel invested, they can’t help but to share it.

The successive editions grew in units and contents. We are aware that the 1909 edition contains 790 recipes. We also know that the 14th edition of 1910 included new chapters for people “with weak stomachs”, a compilation published in Milan by Angelo Dubini in 1858: “La cucina degli stomachi deboli: ossia pochi piatti non comuni, semplici, economici e di easy digestion with alcune norme relative to good governo delle vie digerenti.”

In the 15th edition, 65,000 copies were sold, something unheard of at that time.

Before his death in 1911, we highlight that the 35th edition reached the number of 283,000 copies. Those notable editors then wanted to jump on the Pellegrino Artusi success bandwagon and, from 1900 to the end of the 1930s, many published his cookbook: Salani, Bemporad, Marzocco, Barion, Bietti and Giunt.

The copy was reissued in successive decades by Einaudi, Garzanti, Rizzoli and Mursia until reaching the figure of 1.5 million copies sold.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Although it was Pellegrino Artusi’s most successful cookbook, it wasn’t his last. In 1904, Ecco il tuo libro di cucina, or Here is Your Cookbook with (anonymous) collaboration from the baroness Giulia Turco (1848-1912), or Giulia Turco Lazzari, from Trento, Italy, shared Italy Magazine.

Not only a naturalist and a writer, the baroness had a keen interest in gastronomy, or the art of eating or cooking good food.

“By the end of the 19th century, her main focus was on gastronomy and she created a large recipe file and catalogue maintained between 1899 and 1901 with Pellegrino Artusi,” according to PraBook, a registered trademark of World Biographical Encyclopedia, Inc.

Turco’s involvement with the book remained anonymous, by all accounts, until much later. I can find very little mention of this work, let alone the product, or I would link to it for your convenience.

Death of Pellegrino Artusi

Pellegrino Artusi lived in Florence for sixty years, until his death in 1911 at the age of 91. He didn’t have heirs. In a neat move, and a welcome boon to the area, Pellegrino left his property to the town of Forlimpopoli (I could say that word all day).

His hometown has not forgotten his generosity. The town of Forlimpopoli holds the Festa Artusian. That’s nine days of food and entertainment. Doesn’t that sound fabulous? But wait, there’s more — such as Casa Artusi.

Casa Artusi in Forlimpopoli

The Casa Artusi library holds Artusi’s lounge and study, filled with the books and letters from recipe sharing Italians or those who wanted a copy of the cookbook. You can take cooking classes from Casa Artusi, in-person or virtual, with gentle guidance from “the Grandmas or the Mariettas.”

The volunteers at the centre give their time for free and all bring their own talents and skills. They are collectively named ‘Mariettes’ after Artusi’s loyal assistant and I’d swear she is there in spirit as they chat in Italian and push and pull and laugh and encourage us.

The atmosphere in the room is so good natured that even our kids are being kind to each other and congratulating each other on their far from perfect bread.

Later, when we share the bread with tagliatelle (recipe number seven in the cookbook) in the light filled dining room there is a sense of shared pride that we definitely do not get at home when I wave a rolling pin around and shout at people for not doing the dishes.

With event space and meeting areas, plus a restaurant (Restaurant Casa Artusi), it appears to be a real hub of food-related activity. Every year, The Artusi Prize is presented to someone who is currently doing with food what Artusi did long ago —furthering the conversation.

The actual award is a bust of Pellegrino Artusi by artist Pasquale Manzelli. It is a wonderful thing.

Since 1997, the Town of Forlimpopoli, has been presenting the following awards in honour of its famous citizen, Pellegrino Artusi, author of “La Scienza in Cucina e L’Arte di Mangiar Bene” (The Science of Cookery and the Art of Eating Well).

The two awards are presented during the Festa Artusiana to:

— a person of international fame who has given his/her personal contribution to reflecting upon the relationship between mankind and food. The winners of this particular award come from many different walks of life;

— an award for an internationally famous chef in the specific field of gastronomy.

Past Artusi Prize Winners:

- Wendell Berry (2008)

- Serge Latouche (2009)

- Don Luigi Ciotti (2010)

- Oscar Farinetti (2011)

- Andrea Segrè (2012)

- Mary Ann Esposito (2013)

- Enzo Bianchi (2014)

- Alberto Alessi (2015)

- Carlo Petrini (2016)

- Vittorio Citterio (2017)

- Josè Graziano da Silva (2018)

- Lidia Bastianich (2019)

- Paolo Loprore and Rosa Soriano (2020)

Non-professionals, like Pellegrino Artusi, have a shot at being recognized. “Both the town of Forlimpopoli and the Festa Artusiana would like to dedicate the award to all current-day “Mariettas,” all those men and women who show an interest and flair in the kitchen and apply the basic principles of “The Science of Cookery and the Art of Eating Well,” reads the City of Forlimpopoli website.

Each year, amateur cooks submit their recipe entries before the posted deadline for a chance at becoming one of five home cooks who will then cook their dish during the Festa Artusiana for judging by the panel. The winner receives 1,000 euros.

Previous Marietta Award Winners:

- 2010: Andrea Marconetti (Milan), Pisarei with herbs and legumes

- 2011: Fabio Giordano (Palermo), Fresh busiati with red prawn from Mazara del Vallo and macco di fave fresco

- 2012: Raffaella Bugini (Valbrembo), Risotto al moscato di scanzo with biligòcc and strachitund fondue

- 2013: Rolando Repossi (Casatenovo) Ravioli di grandma Costantina

- 2014: Francesco Canu (Sassari), Culurgiones a ispighitta cun pumata

I’m having trouble locating the info on the rest of the winners’ list. If you should know the names, locations, and shared dish, please let me know using my contact form or a comment below. Thank you.

Is the Science of Cooking and the Art of Eating Well Still Relevant Today?

It is true that man does not live by bread alone; he must eat something with it. And the art of making this something as economical, savory and healthy as possible is, I insist, a true art.

Pellegrino Artusi, The Science of Cooking and the Art of Eating Well.

For many Italians, the answer is a resounding, “Yes,” or, perhaps I should say, “Si?” The English cookbook editions include watercolor illustrations by renowned Italian artist Guiliano Della Casa (1942-). But as for today’s relevance, well, that was put to the test not too long ago.

On August 10, 2014, Pellegrino Artusi’s work was judged at a mock trial by Sammauroindustria at La Torre – Villa Torlonia, asking the question, “Is Pellegrino Artusi’s cuisine modern or outdated?” Since 2001, Sammaruoindustria has promoted trials featuring important historic figures.

After hearing both sides from relevant representatives, the jury, made up of audience members, vote. For the Pellegrino Artusi trial, the prosecutors and defense were members of the food community, highly-regarded writers or chefs/restaurant owners.

Judge

Gianfranco Miro Gori (President of Sammauroindustria)

Prosecutor

Alfredo Antonaros (writer) and Silverio Cineri (chef)

Defense

Alberto Faccani (chef) and Piero Meldini (writer)

In the case of Pellegrino Artusi, 288 out of 372 people voted in favor of Pellegrino, 76 against, and 8 undecided votes (according to La Piazza). Audience members aside, there are plenty of others in Italy (and throughout the rest of the world) that would agree with Pellegrino Artusi’s relevancy.

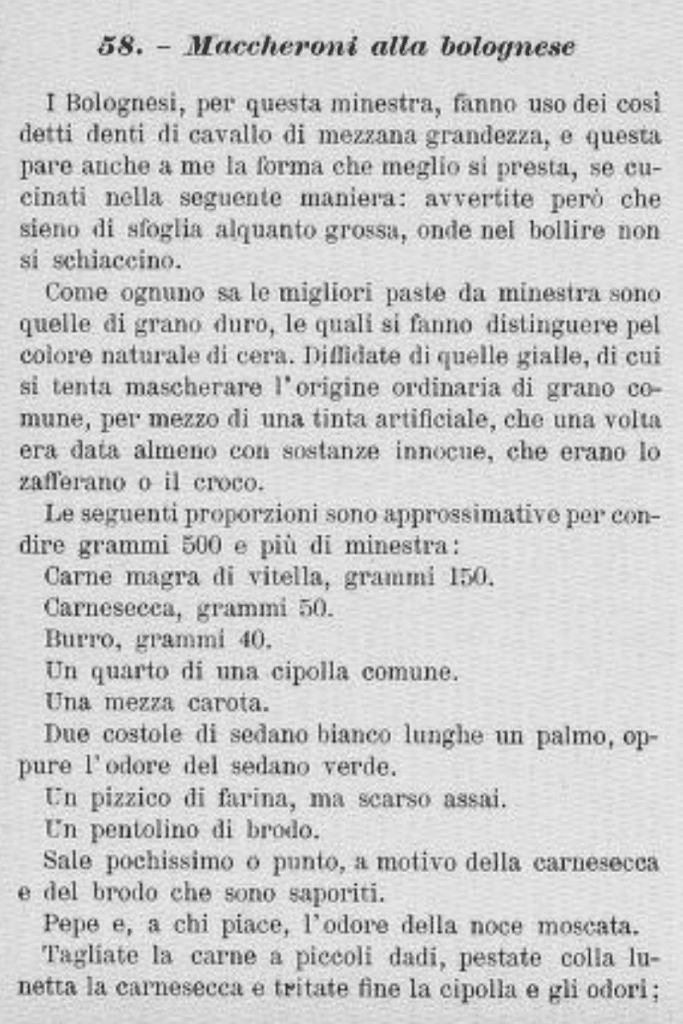

Consider his recipe for Bolognese.

Artusi’s bolognese isn’t far off most modern recipes and is almost a mirror image of the “authentic” bolognese recipe sanctioned by the Accademia Italiana della Cucina in 1982.

The only major differences involved swapping veal for beef and adding an additional cup of whole milk and half-cup of wine (though Artusi’s sauce could be made more decadent via the inclusion of dried mushrooms, truffles, chicken liver and half a glass of cream).

But did Artusi’s original recipe opt for spaghetti? Though “maccheroni” was a catch-all term that could have indicated any form of pasta, he states that pasta that resembled “horse’s teeth” was preferable.

You can take a look at the two recipes below.

Ingredients for Pellegrino Artusi’s recipe for Bolognese from his book:

Ingredients for the “authentic” recipe approved by the Accademia Italiana della Cucina in 1982:

300 g coarsely ground beef

150 g pork belly

50 g yellow carrot

50 g celery stalk

30 g onion

300 g tomato sauce or peeled tomatoes

½ glass of dry white wine

½ glass of whole milk

a little broth

extra virgin olive oil or butter

salt

pepper

½ glass of whipping cream (optional)

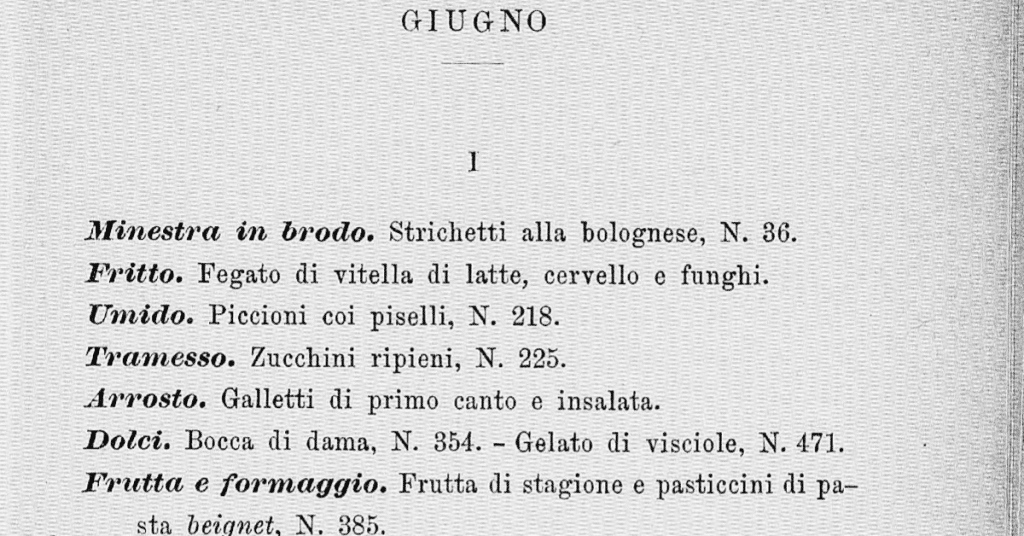

That isn’t to say that things haven’t changed. After all, food and how people handled it was changing during Pellegrino’s time, or he wouldn’t have received so many letters (and published so many editions). Memorie di Angelina shares a June menu from Artusi’s book.

I’ve included the image from the original Italian version of The Science of Cooking and the Art of Eating Well directly below.

The author of the piece mentioned above then describes how Italians would approach such a menu today:

It is the structure of this meal, more than the dishes themselves, that shows how Italian cuisine has changed. Besides the sheer number of courses, they do not follow the modern structure of antipasto, primo, secondo, contorno and dessert where each course is defined by its principal ingredient.

Artusi structures his meal by cooking method: the first course is a soup (a kind of pasta in brodo), followed by a mixed fry of veal liver, sweetbreads, brain and mushrooms, then stewed pigeon with peas, then a stuffed and baked zucchini dish as a ‘tramesso’ or intermezzo, then a roast chicken with salad, then sweets (lady fingers and cherry ice cream) and finally fruits and cheeses. (People obviously had hearty appetites back then…)

It’s interesting to see how things have changed and how they have stayed the same, at least in one Italian’s view. I’d love to learn about other examples. Do share if you have such knowledge.

Pellegrino Artusi Changed Everything

Still nowadays, you can find this recipe book in almost every Italian kitchen and it is very common to hear someone while preparing a dish asking to [sic] his helper “look what Artusi says”.

Marcello & Raffaella Tori, Pellegrino Artusi – The Pioneer of Italian Gastronomy, Slow Travel Tours, April 5, 2020.

Pellegrino Artusi didn’t just write a cookbook with measurements and instruction. He added his insights, collections of recipes from across the new country that he’d been collecting for years, later including recipes sent his way after his first edition was published, all while introducing standardized Italian.

Artusi’s work aimed to reflect the traditions of the whole country, not denying the extraordinary variety of local traditions, rather putting them into circulation, making them known and shared.

This project – also a linguistic one: telling the kitchen in a “national” language that everyone could understand – worked in a “inter-active”, almost a collective way, involving the many readers who sent Artusi suggestions, advice, and new recipes.

That’s why La scienza in cucina e l’arte di mangiar bene became a sort of collective work, adding more and more recipes over twenty years and fifteen editions, and published up until Artusi’s death (1911).

This was far more than a simple cookbook. It was a game changer. He is credited with building the customs of the fledgling country as well as the language. Each of his subsequent editions included alterations to the recipes and the language to reflect the time.

The three books that made Italy were Manzoni’s I promessi sposi, Collodi’s Pinocchio and Artusi’s The Art of Eating Well. That period in every Italian family there were these 3 books and they got used to the idea of Italian identity.”

After a bit of browsing, I’ve learned that his book is often referred to simply as “L’Artusi.” Further digging revealed that the cookbook has long been shortened in that way. Alfredo Panzini (1863–1939), a novelist and a lexicographer (he wrote a dictionary on modern words not found in the common dictionary), included Pellegrino Artusi.

Two decades after Pellegrino’s death, the 1931 edition of the Modern Dictionary (a compilation of words not found in other dictionaries), included this (as translated from Italian):

Artusi: par excellence cookbook. What a glory! The book that becomes a name! How many writers had this fate? He was the Artusi of Forlimpopoli (1821-91), banker, cook, bizarre, dear gentleman, and very beneficial, as he demonstrated in his will; and his treatise is written in good Italian.

And he was neither a man of letters nor a professor.

Pellegrino Artusi Recipes

It isn’t everyone who can boast of a dictionary entry. It isn’t everyone who can hold onto popularity and usefulness for so long after their death either. Bloggers, food writers, cookbook authors, and home (and pro) cooks everywhere still turn to Pellegrino’s book.

Craving more? Discover a bevy of Pellegrino Artusi recipes and commentary from the following websites and blogs:

- Aglio Vestito: Chicken alla Marengo Recipe by Artusi: Pollo alla Marengo

- Amio Pulses: Side Dish of Pureed Lentils

- Chewing the Fat: Pellegrino Artusi’s Bolognese

- La Cucina Italiana: Recipe No. 7 by Pellegrino Artusi: Cappelletti all’Uso di Romagna

- Cuoche in Vacanza: Italian Carnival fried dough: i Cenci!

- Eat like a Girl: Pellegrino Artusi and a Recipe for Perfect Pasta Dough (Photo Illustrated)

- Emiko Davies: Artusi’s Semolina Cake

The Globe & Mail: Cappelletti all’Uso di Romagna - Italian Tribune: Crescioni, Cauliflower Frittata, and Pesce a Taglio in Umido

- Luca’s Italy: Torta di Noci: Walnut and Chocolate Cake: Chestnuts and Truffles TV

- Pastabites: A recipe from history – Cat’s tongues

- The Spruce Eats: Trippa – Tripe in Traditional Italian Cuisine

- Tammy Circeo: Italian Sausage with Grapes & Herbs

- The Washington Post: Artusi’s Donzelline (Little Damsels)

Yes, I will add in new links to websites and blogs with Pellegrino Artusi recipes as I find them (or you send them to me).

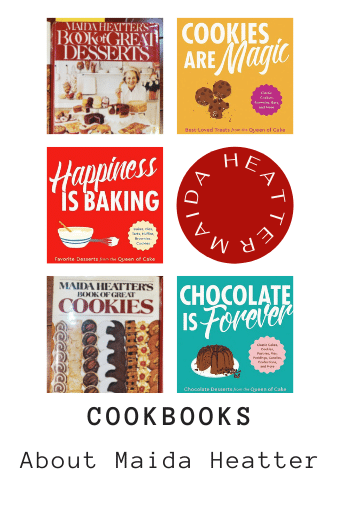

Pellegrino Artusi Cookbooks

Artusi: Cookery book. How glorious! The book has become a noun. How many writers are there who could boast a similar destiny?

Alfredo Panzini, Modern Dictionary, 1931.

I usually arrange an author’s cookbook by the year of publication. However, we’ll have to mix it up a bit with Pellegrino. Not all editions are made equal. I include the best of the best, so translated versions appeared much later.

Do note that “Science of” (2003) and “Eating Well” (1997) are the same book, but by two different publishing houses, so maybe not quite the same. Avoid the 2012 version called Italian Cook Book by Olga Ragusa. That version omits Pellegrino’s personality from the recipes.

The Penguin book Exciting Food for Southern Types is not the full version either. Stick with the cookbook editions from Random House (1996) or the University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division (2003) for the book in full. Buon appetito.

Fascinating post! I think I first read about Artusi in a post about apricot jam by Emiko Davies, but you have reminded me why I really should look for his book. Your recommendations are always good. I picked up The Picnic Gourmet from your picnic post and it is as charming as you suggested.