Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, I may receive compensation at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support.

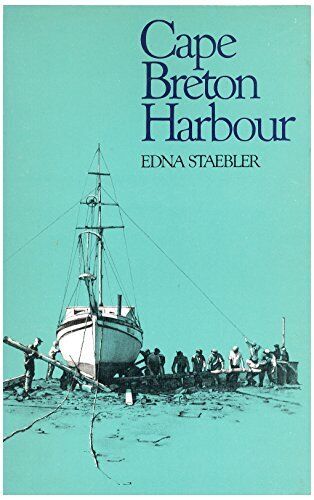

At the time of this writing, my cookbook collection is yearning for several of Edna Staebler’s cookbooks ). I know you’ll like getting to know today’s featured author.

All you Canadian readers out there already know and love Edna Staebler. I think it’s time for the rest of the world to meet her too. Say “hello” to Edna Staebler, a unique cookbook author known for truly immersing herself in her subject.

- A (Brief) Overview

- Edna Staebler's Early Career

- Edna Staebler Writes a Cookbook

- A New Beginning: After the Divorce

- Edna Staebler and the Cookie Wars

- Edna Staebler Golden Years

- Edna Staebler Legacy

- Edna Staebler Cookbooks Still Popular Today

- Edna Staebler's Cookbooks

- Biographies from Edna Staebler

- Related Resources:

A (Brief) Overview

Edna Staebler was born January 15, 1906 in Kitchener, Ontario, Canada (called Berlin in those days), in a home where her mother and a maid cooked. While Edna thought she would like to write a book one day (according to her “Food that Really Schmecks” cookbook), she didn’t know what she should write.

She wrote anyway — lengthy journal entries detailing her writing struggles.

A lack of support from a spouse and a parent would be enough to discourage most people from pursuit. While Edna may have sometimes felt discouraged, as evidenced by her journal entries, she didn’t stop writing.

Edna Staebler’s husband, at the time, told her that she wasn’t a “real writer” until she was published. Her own mother didn’t think she had any talent (her mother did change her mind later, at least). Thank the kitchen gods that Edna Staebler ignored them both (at least, as best she could), and kept on writing.

In 1961, Edna Staebler – writer, homemaker and future cookbook author – was suffering the sort of black misery that comes from divorce. Her husband of 28 years had told her their marriage was over. He was leaving her to marry one of her best friends – the woman she had confided in about her husband’s drinking, the unkind words he hurled at her while drunk, his constant philandering.

The couple had no children; they hadn’t had sex in the past 22 years. Staebler was 55, with precarious employment as a freelance writer. She thought she would grow old alone, impoverished and unhappy, and that her best years were behind her. She cried herself to sleep every night for a year.

Edna Staebler could have turned bitter from decades of wasted years in a horrible marriage, years her husband kept cheating on her while he wouldn’t so much as kiss her, while hurling insults her way, and drinking himself into oblivion.

She wouldn’t have known about the variety of addictions (or habit-forming patterns of behavior) out there — and that her husband checked several boxes. Edna could have taken the awful things he said to her to heart and started believing them herself.

If you’ve ever loved someone who has addictions, you know how easy it is to, over time, start believing the horrible things they rant about you. You learn (with the help of a good therapist) they are really only projecting their insecurities back onto you.

Edna could have given up on her writing and found work elsewhere, like so many other women of that era, like so many women now. Not that she had many choices:

In the early 1960s women were stereotyped as happy wives and mothers. The only jobs available to them outside the home were as teachers, secretaries and nurses. Society felt that a woman’s goal was to get married, have children, and be a skilled homemaker.

Of course, that’s forgetting jobs like department store clerks, factory workers, and switchboard operators. But, the world of work wasn’t so big for women (and they were paid less while in it too). Women (single, divorced, or widowed) usually had to bring a man with them as a co-signer for a credit card, according to the Smithsonian Magazine, or to open a bank account, shared Little Things.

Women weren’t allowed to run the Boston Marathon. Sneakers for women wouldn’t even be available until the 1980s, according to The Bustle.

But, Edna didn’t. Long before her marriage ended, she developed friendships and long-term letter writing companions. She decided to take solo trips, first around her area, and then branching out. Edna’s trip from Ontario to Nova Scotia to German-immigrant city Lunenburg resulted in a flurry of letter writing to her husband.

Her return home after weeks away earned her writing praise from her husband.

Edna did sometimes yearn to leave her husband, the big house, and her golf club friends behind, according to Edna Staebler’s biography. But what woman could easily do that during that time period? During any time period? When divorce became a reality, and took a best friend away from her too, what was Edna Staebler going to do?

Edna worked on finding happiness and being a part of people’s lives. By all accounts, she felt like we were all part of something together, and she loved people, even when they didn’t behave in expected ways.

Through everything, she worked on her writing.

Edna Staebler’s Early Career

Edna may have always wanted to write a book, but her path fresh out of college took her in a different direction. After graduating college in 1929, Edna worked as a clerk in stores, but was told she had “too much imagination,” according to the introduction in her “Food that Schmecks” cookbook.

She turned to teaching at Ingersoll.

Her subjects included French, English Lit, and Physical Education for the young ladies. After a year, twenty-six-year-old Edna was caught turning a somersault in the front lawn by the school principal. She was fired by the school board for being too close in age to the students. Can you imagine? She was even the woman responsible for their physical education. The next year, Edna married.

After marriage, Edna continued writing, both one-act plays and in her journal, as she had been doing since she was 16, and would continue for more than 80 years. Edna developed her idea for a book, “Neil’s Harbour,” after a solo trip in 1954.

Since Edna’s home life was so terrible, and her husband had trips of his own, Edna started to set out solo. She enjoyed meeting people and learning their stories. When she was at home, work on her own projects stalled.

Edna frequently had a slew of people in and out of her home: Neighborhood children who wanted to bake cookies, friends calling, and a series of people her husband had met, former soldiers, who wanted a visit and encouragement, too.

Edna turned none of them away. She was a writer, but there were meals to get, people to entertain, curtains and dresses to be sewn. Perhaps it was inevitable that family and visitors saw Edna’s writing as a hobby, a more eccentric one than sewing, but still a pastime, something for her spare time.

Every established writer reading that quote above is nodding along.

Getting started as a writer does have that hobby kind of edge to it. When your words move from something no one sees. to something published. and available to the world? Well, that changes everything.

Edna had been stranded in Nova Scotia during a trip in August 1945. At the time, she was traveling with two friends, yet one of those friends had romantic attentions. His frequent come-ons made her uncomfortable, so she asked to be left behind in a town they were passing through, and she was — for three weeks in a tiny town, Neil’s Harbour, where she didn’t know a soul.

It was scary for Edna at first, as it would be for anyone. Yet, she ended up staying for three weeks, because she enjoyed her experience so much.

“She was not Mrs. Staebler but ‘our Aidna’ who had arrived like a gypsy and stayed to become almost one of them,” wrote Veronica Ross in “To Experience Wonder.” What a nice change for Edna and her horrible home life.

After her trip, she worked on her book idea. Always community-minded, Edna met Dr. John Robins, a Governor General’s Award–winning novelist and professor at the University of Toronto’s Victoria College, while at her Canadian Women’s Club meeting.

John became her mentor, offering encouragement and suggestions to tighten her work. His enthusiasm for her writing did much to keep her going, even as her marriage fell apart.

Edna tried to find a place for her finished manuscript, but after years of getting turned down, someone suggested she turn it into a magazine article. For six weeks, Edna worked on her story about the fishers who spear swordfish.

Then, breaking every “rule” that said you must submit your work via snail mail, and not hand it over in person, Edna strode into the office of Maclean’s, and handed Duelists of the Deep over to then managing editor, Pierre Berton.

Maclean’s, in case you don’t know, was probably Canada’s most popular semimonthly general interest magazine that began in 1905 (until 1978 when it became a weekly news magazine, according to The Globe and Mail.

It was bigger than the typical magazine now — and colorful, full of Canadian pop culture, entertainment, and then some.

Maclean’s covered a lot of bases at the time and covered them well. Today, Maclean’s is published monthly featuring “national current affairs and news.”

That $150 check from Maclean’s did much to spur Edna on. We’ve all been there. Tangible evidence of your skills go far in terms of motivation. Edna went on to write pieces for Chatelaine, Reader’s Digest, Star Weekly, Canadian Living, and Saturday Night magazine.

In a rare move, Edna was assigned a piece featuring the Old Order Mennonite Amish in 1950, according to a Maclean’s article. While working on what would become How to Live without Wars and Wedding Rings (I link to it below, so hang on) for Maclean’s, Edna moved in with an Old Order Mennonite Amish family.

That wouldn’t be the last time Edna would try to find somewhere to stay and a way “in” to better understand a community.

Staebler’s participatory reporting made her a pioneer of what has come to be known as literary journalism. Her technique was to knock on a stranger’s door and ask to stay.

In a 1952 Maclean’s story about Hutterites in Alberta, she jumped on a bus to Waterton Lakes with a plan to find a way into the community. En route, she met a woman from the Old Elm colony who said she could stay with her for a few days.

Is that the way journalists normally handle a story? No. Not at all. But, Edna didn’t consider herself a journalist. She wanted to keep her style, not dull it down with facts and figures. Plus, she made friends — life-long friends — whose consistent correspondence led Edna to write about Old Order Amish cooking for a different article published in Maclean’s in 1954.

Edna Staebler Writes a Cookbook

If you are in the Guelph, Ontario area, visit the University of Guelph Edna Staebler Collection to read a host of Edna’s magazine articles.

Take a look at her articles, now made available for FREE through Maclean’s magazine, below:

- Duelists of the Deep, July 15, 1948

- How To Live without Wars and Wedding Rings, April 1, 1950

- The Isle of Codfish and Champagne, November 1, 1950

- The Boats that Sail a Warpath, July 1, 1951

- Maggie’s Leaving Home, November 1, 1951

- The Lord Will Take Care of Us (about the Hutterites of Alberta), March 15, 1952

- The Happily Married Cities, October 1, 1952

- Those Mouth-Watering Mennonite Meals, April 1, 1954

- The Unconquered Warriors of Ohsweken, November 12, 1955

- Why the Amish Want No Part of Progress, September 27, 1958

Check out these interesting articles that don’t deal with food. It’s a great example of her writing style, including the article that made her a published writer.

Funny thing, after I read “Maggie’s Leaving Home,” I wanted to know what happened to Maggie. A quick Internet search led me to see the obituary of Norman Henry Ingraham, a friendly looking man who passed away in July 2020, at 87 years old.

The obit mentions how Norman served in the military, and near the end, someone named Maggie is a sibling. Norman is mentioned in Edna’s article as the brother who is “away in the Army because he wants to travel.” Maggie’s last name is different so I know she married.

Of course, the next day I discovered how Edna wrote a follow-up book to share how the people she wrote about were doing. Isn’t that funny? The first edition was titled: “Whatever Happened to Maggie and Other People I Have Known.”

The second edition switched the title to Places I’ve Been and People I’ve Known: Stories from Across Canada. I had no idea that that’s what the book was about, so I’m happy to know I can find out more.

I guess I’m not the only person wondering what happened to Maggie.

Those Amish Mennonite pieces were what led to a publisher asking Edna Staebler to write a cookbook. Edna curated Amish recipes to share with an “English” audience (“English” is how Amish describe non-Amish). “Food that Really Schmecks” was the result, making Edna a Canadian household name.

The cookbooks, she says, were an unplanned, but satisfying “accident.”

As with many (good) cookbooks, the introductory chapters are a delight to read where she describes friends from the local Mennonite community (founded by families that migrated north from Pennsylvania — and originally from Europe). She waxes rhapsodically about her beloved Waterloo County and its entrepreneurial roots.

For all the wonderful writing Edna did for Maclean’s and other publications, her cookbooks are what Canadians (and others) remember her for the best.

By focusing on the Mennonites and their cuisine, Edna (who was not a Mennonite herself, but lived surrounded by them in rural Waterloo County) created a collection of recipes with timeless appeal. That’s because her Mennonite friends, whose lives and kitchens she installed herself in to collect recipes, very much practiced the kind of farm-to-table cooking that we’ve lately been rediscovering.

For the Mennonites, fruits and vegetables were either fresh from the garden, pickled or dried, meat was hand-reared and minimally processed, and the dairy products were rich and abundant. Butter, sour cream, bacon and brown sugar gilded everything. It’s not trendy or cosmopolitan food, but it’s deeply appealing in a rustic, elemental way.

It’s the kind of food people wanted to make. Those simple dishes were what folks grew up with or were surrounded by. It’s what their mother or grandmother had made. Homey, comfort food.

While Staebler was best known as a cookbook writer, she didn’t always embrace the role. At first, she was embarrassed to talk about working on recipes with her writer friends (although that would change, when she realized how much happiness readers derived from Schmecks).

She also faced stereotypes: there was a tendency for the public to pigeonhole her as a docile, grandmotherly, stay-at-home cookie-baker — likely something many female cooks and food writers of her generation faced.

“She always said, ‘I’m not just a sweet dumpling of a cookbook writer,'” says Ross, noting that Stabler was very independent — and feisty when it came to pushing publishers on matters of marketing and royalties. “She was approachable, but she was very intelligent and astute.“

Edna Staebler’s cookbooks were good, fun reading. If you, like me, enjoy reading a cookbook for the recipes AND for the commentary, Edna’s are fantastic.

(I somehow snagged a used copy at Mondragon Books in Lewisburg, PA

A New Beginning: After the Divorce

After years of solo trips here and there, Edna’s life with Keith ended in 1961. He had spent time in rehab, and upon his return, asked for a divorce. He ran off with her best friend from her college years, the same woman Edna confided to about his drunken temper, his emotional abuse, and his affairs.

Edna kept their Sunfish Lake cottage. It was the perfect place to regroup, focus on her writing, and entertain.

In 1968 Staebler wrote, in her book’s introduction, about the first dinner party she ever gave. Fellow writers were visiting her cottage at Sunfish Lake (in Southern Ontario) from Toronto. The following passage sums up what Edna Staebler’s food was all about.

I believe it’s as good a description of comfort food as you’ll find.

“My dinner would not be elaborate, or exotic, with rare ingredients and mystifying flavours; traditional local cooking is practical: designed to fill up small boys and big men, it is also mouth-wateringly good and variable. My guests from Toronto arrived. I served them bean salad, smoked pork chops, shoo-fly pie, schmierkase (spready cheese) and apple butter with fastnachts (raised doughnuts).

At first they said, ‘Just a little bit, please,’ but as soon as they tasted, their praise was extravagant — lyrical to my wistful ears. They ate till they said they would burst. They ate till everything was all (nothing left).“

Those writers and editors, according to Edna, had traveled the world, had eaten in the fanciest of places, and wouldn’t be bowled over by just anything. Yet, she realized that those people wouldn’t even be able to find these kind of recipes in their “epicurean cookbooks.”

She had a point. Good, simple food, done well, leaves a long-lasting impression.

Edna never stopped entertaining. People made the trip to Sunfish Lake for time with Edna, and she was all too happy to oblige. What a wonderful thing.

Publisher Jack McClelland once suggested during such a visit that Edna write a book about Sunfish Lake and celebrated pilgrims who had made there way there.

Besides virtually everyone mentioned to this point, that list would include Margaret Laurence, a youthful Neil Young, Royal Bank President John Cleghorn, Marion Engel, Paula Todd and Peter Etril Snyder, as well as Eva Bauman, Nancy Martin and Libby Kramer — the Mennonite women who shared their recipes-via Edna — with the world

Edna’s cookbooks led to another unforeseen event. Edna became involvement in a war.

Edna Staebler and the Cookie Wars

Edna Staebler was once a neutral party to war. A cookie war. It began because of Edna’s recipe for rigglevake cookies in her first cookbook, Food that Really Schmecks.

No one intimidated Staebler, and certainly not lawyers for billion-dollar cookie companies. Don Sim, a Toronto lawyer representing Procter & Gamble (P&G), which had recently purchased the baked goods company Duncan Hines, was about to find that out.

In 1984, he called Staebler to ask if he could visit Sunfish Lake. P&G had filed a suit against Nabisco (the National Biscuit Company) for infringement of a patented formula for crisp, chewy cookies. Nabisco, the cookie industry’s top company, commanded 80 percent of the market.

The argument between the two corporations centred on rigglevake cookies (Pennsylvanian Dutch for “railroad cookies”), a combination of molasses and old-fashioned sugar cookies. The swirly design of the two types of dough made them look more exciting than they tasted, but that wasn’t the point. Nabisco argued that P&G couldn’t patent the recipe because it appeared in Food That Really Schmecks, and published recipes cannot be patented.

Sim’s job was to prove that P&G’s cookies were different from rigglevake cookies, so he asked to watch Staebler’s Mennonite friends bake, promising to pay them for their time. Staebler was protective of her friends, but was also pretty sure they would be happy to make money.

This began a strange relationship between the Mennonites and lawyers representing both major companies, hoping to prove the rigglevake recipe was, or was not, crisp and chewy. Many cookies, 182 days of pretrial testimony and 200 witnesses later, the case was settled out of court.

From what I gather, it seems that both companies were using Edna’s curated recipe that had been included in her “Schmecks” cookbook, but P&G tried to declare that their company had it “patented.” Can you imagine?

In the end, I believe I saw that Edna sided with Nabisco (which makes total sense) but I can’t find where I read that so … yeah. Sorry about that sloppy bit of reporting there and the lack of a link to back it up.

The incident “inspired a play and movie script,” according to the University of Waterloo Mennonite Archives of Ontario. A lawyer from the “cookie wars” even made the trip from British Columbia to be part of Edna’s 95 birthday celebration.

Edna Staebler Golden Years

You didn’t expect Edna Staebler to slow down, did you? I didn’t think so. And, she didn’t.

Canada’s internationally acclaimed cookbook author, shows off her well-thumbed wall calendar. Most days’ white squares are filled with her notes, indicating appointments or that visitors are expected. It’s a schedule that reflects her enormous capacity for making friends — and shows remarkably few concessions to her advancing years. She gave up driving only at 95.

Now 97, she doesn’t hesitate, when pressed, to state what she dislikes most about being that age. “I hate it when people are patronizing,” she says with such clear-eyed intensity one wonders who would dare. “I hate it when people treat me as if I were feeble-minded.”

To read more of Edna Staebler’s fascinating personal life and adventures, and I suggest you do, take a look at the books listed far down the page below (after her cookbooks, of course).

Edna Staebler Legacy

By Staebler’s own admission, she had “no qualification for writing a cookbook except that I was brought up and well fed in Waterloo Country.” (In fact, in her 60s, she owned only two cookbooks: a Betty Crocker classic and a Mennonite one, both gifts.) But she didn’t need to be a chef: it was her ability to use food as a storytelling vehicle to evoke home and hearth, and to open a window into the houses of others, that drew readers.

In 1991, Edna established an award for creative non-fiction, awarded annually by Wilfrid Laurier University. The Edna Staebler Award for Creative Non-Fiction is the only one of its kind in Canada for the genre.

Then there’s the Edna Staebler Visiting Author position, and the Edna Staebler Laurier Writer-in-Residence program with a variety of options available to other genres.

I found food writer Jasmine Mangalaseril description of the time she met Edna Staebler. It appeared on her older blog, Confessions of a Cardamom Addict (someone as obsessed with cardamom as I am).

Jasmine explained blogging to Edna and they chatted about writing during her visit:

We visited my blog and called up my post about her apple fritters. Our friend praised my writing—and I blushed. Edna gave me advice and talked about her writing process. We are very similar.

She beamed when she found out that I approach my personal writing in much the same way as she wrote: pages of handwritten scripts tucked in cabinets and books; pieces are written and re-written; we read voraciously.

I don’t know if she ever read this blog—we explained the Internet and blogging to her. She was interested in the thought of all those people from all over the world stumbling onto this little bit of espace. I know she liked that photo and thought that the chocolate-maple syrup I made was quite good.

I learned that Neil Young once stayed at Sunfish Lake. I knew she was friends with Pierre Berton and W.O. Mitchell. We talked about books and food and cats. She was bright and aware. She asked questions and reminisced.

Edna Staebler passed away September 12, 2006. She was 100 years old.

What would Edna think knowing her first cookbook is available on an iPad, and that people are still writing about her work today? I think she’d be tickled by all the people who can access her books and recipes, who may not have been able to find her work otherwise.

She was community-minded. Edna loved a party, people, and great gobs of friends.

Edna was president of the Canadian Federation of University Women from 1943-1945, a member of the Toronto Women’s Press Club, the Media Club of Toronto, the Canadian Author’s Association, and the Writers’ Union of Canada, according to Laurier.

The first used book sale was the vision of the late Edna Staebler, writer, philanthropist, and member of CFUW K-W. In 1964, Ms. Staebler suggested organizing a used book sale to raise funds to support local scholarships.

Since then, funds raised at their annual book sale have helped CFUW K-W recognize and encourage educational excellence by offering scholarships and awards at the secondary and post-secondary levels in the Kitchener-Waterloo Region, and nationally. Since its founding in 1922, CFUW K-W has awarded close to $500,000 in scholarships.

A host of awards and recognition were given to Edna for her achievements. In piecing her achievements together, I am sure I’ve missed a few. My apologies.

Edna Staebler’s awards include the following:

- Canadian Women’s Press Club Award for Outstanding Literary Journalism (1950)

- Kitchener-Waterloo Woman of the Year (1980)

- Honorary Doctor of Letters degree from Wilfrid Laurier University (1984)

- Waterloo-Wellington Hospitality Award (1988)

- Province of Ontario Senior Achievement Award (1989)

- Kitchener-Waterloo Arts Award (1989)

- Silver Ladle Award for Outstanding Contribution to the Culinary Arts (1991)

- Governor General’s Commemorative Medal (1993)

- Regional Municipality of Waterloo Volunteer Award (1994)

- Cuisine Canada’s Lifetime Achievement Award (1996)

- Member of the Order of Canada (1996)

- Inducted into Waterloo Region Hall of Fame (1998)

The Order of Canada, in case you don’t know (and because I didn’t), is how Canada “honours people who make extraordinary contributions to the nation,” according to the Governor General of Canada website. The award began during Canada’s centennial year, or 1967.

Since then, more than 7,000 people have been awarded this honor. People, like Edna, who earn this award do so because “They exemplify the Order’s motto: DESIDERANTES MELIOREM PATRIAM (“They desire a better country”).”

For Edna, I think it was about helping people understand what was so great about the people they didn’t understand.

Edna Staebler Cookbooks Still Popular Today

Research Foundation, Vol. 10, Issue 1,

January 2007.

People still turn to her cookbooks for good, easy food with recipes they can trust. It is like cookin’ in the kitchen with a friend, what with all her little stories accompanying so many recipes—and what could be better than that?

I felt full just flipping through the book, and Staebler’s appreciation for food sometimes made me laugh out loud. In the recipe for Apple Sponge Pudding, she notes: “This should serve eight people, but it probably won’t.”

No, you won’t find glossy images of picture-perfect cake after camera-ready bread after expertly-styled casseroles. That’s not the way “Food that Really Schmecks” works, which is kind of fitting, considering the recipes are from the homes of Amish Mennonites.

Edna’s instructions are succinct and straightforward. Not precious in any way, these recipes are easy to follow whether you are an expert or a novice.

I can truthfully say that because I was in my early teens and certainly a novice when I first used this book. And her notes about the recipes are charming. You get a lovely insight into her life and her friends.

Edna wasn’t one of those prolific cookbook writers, churning out new titles year after year. But, the cookbooks she produced have found a permanent place on many a cookbook shelf.

Edna Staebler’s Cookbooks

WLU – 16008 – Edna Staebler Award from Memory Tree on Vimeo.

Did you know you can bake with Edna Staebler? Yes, you can. Take a look at this segment from “Loving Spoonful” featuring Edna. She’s baking Backwoods Pie.

“Loving Spoonfuls” featuring Edna Staebler baking Backwoods Pie in her Sunfish Lake cottage. (November 14, 2000) Season 1, Episode 8. (Amazon).

Here are the Edna Staebler cookbooks you’ve been waiting for. Do note that I included both copies of “Maggie” since they are both available and easy to find. That way, you can choose the edition you prefer.

Hi! Great article! Not much long-form reading left on the Internet, nowadays.

The quote you attribute to “Natty Physicist” actually comes from a press release sent to Radio Waterloo by Cheryl Ambrose, BSc PhD, VP Advocacy, Canadian Federation of University Women (CFUW); Cell: 519-546-89110; cheryl.d.ambrose@gmail.com

Feel free to keep the link to the Radio Waterloo website, it’s as permanent as we can make it (and I’ll bet that press release isn’t available anywhere else). But the credit should go to Cheryl Ambrose.

Thanx,

–Bob.

Ack! Thank you so much for the catch, Bob. I’ve got that updated now. I appreciate it! 🙂