Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, I may receive compensation at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support.

Pudding, custard, mousse—they are all classics in my book. Mousse kind of screams “sophisticated!” but it isn’t any harder to make a mousse than it is to make pudding or custard. Even pudding can look fancy if you jazz it up. As similar as these dishes may appear, they each have a unique history.

Let’s take a look at the invention of chocolate mousse, pudding, and custard. We’ll peruse a few regional dishes and see how they got their start too. From persimmon pudding to banana pudding, chocolate mousse to custard, some of these dishes have roots that go way back.

- Puddings in History

- Hasty Pudding and Indian Pudding

- Banana Pudding Wasn't Always Southern

- Persimmon Pudding

- Dessert Pudding as We Know It Today

- Chocolate Pudding

- All About Dessert Mousse

- Henri Mari Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa is NOT the Inventor of Chocolate Mousse

- The REAL Inventor of Chocolate Mousse

- A Word about Custards

- Regional Custards

- Bonet

- Pasticciotto Leccese

- Pastel de Nata

- Custard in the United States

- Boston Cream Pie

- That's a Tasty History

- Related Resources:

Puddings in History

Depending on what side of the globe you are on, pudding can be savory or sweet. It can also mean a general term for dessert, or a specific item, like here in the US.

Pudding, any of several foods whose common characteristic is a relatively soft, spongy, and thick texture. In the United States, puddings are nearly always sweet desserts of milk or fruit juice variously flavoured and thickened with cornstarch, arrowroot, flour, tapioca, rice, bread, or eggs. The rarer savoury puddings are thickened vegetable purées, soufflé-like dishes, or like corn pudding, custards. Hasty pudding is a cornmeal mush.

Pudding, Britannica, Accessed 4/13/2021.

Puddings are in the custard family, which means they have been around a long time. A LONG time. But, back in Roman and Medieval times, puddings were meat-based. I know, that kind of grosses me out too. Meat pudding. It sounds like a Simpsons episode or the punch line of a bad joke or the punch line of a bad joke IN a Simpson’s episode.

In fact, a once common saying includes the term “pudding,” such as “the proof is in the pudding.” Or is it “the proof of the pudding?”

ZIMMER: Back then, pudding referred to a kind of sausage, filling the intestines of some animal with minced meat and other things – something you probably want to try out carefully since that kind of food could be rather treacherous.

INSKEEP: OK. So, over the years, the original proverb has evolved. The original was the proof of the pudding is in the eating. It was shortened to the proof of the pudding, and then here in America, it morphed again to the proof is in the pudding. Apparently, the proof of the listening is in the correcting.

Steve Inskeep and Ben Zimmer, The Origin Of ‘Proof Is In The Pudding’, NPR, August 24, 2012.

I’m not sure I’ve ever heard anyone use the entire expression above. Have you? Is that a dead saying? I’m thinking maybe. I’ve only heard, “the proof is in the pudding.” Thank you Middle Ages for creating an early version of the pudding we know and love. Who knows when dessert pudding would have made an appearance otherwise?

While bread is always at the center of this dish, the original recipe was not as luxurious as the custardy treat we make today. Frugal cooks in 11th and 12th century England, where it originated, could only afford to soak the bread in hot water before squeezing it dry and then adding a mix of whatever sugar and spices they had on hand.

After the 13th century, when the recipe started to include eggs, milk and a type of fat to soak the bread in, the dessert was more commonly referred to as ‘bread and butter pudding’ rather than ‘poor man’s pudding’ before being shorted further to only ‘bread pudding.’ If you’re wondering why it is called a pudding, it’s because this dish includes a cereal base (the bread) and has a soft and spongy consistency after baking.

Soaking bread in water and squeezing it dry doesn’t sound all too appetizing to me. It gets worse, at least it does if you aren’t into black pudding. I’m not talking about chocolate either.

To focus attention on British usage (of the word pudding) is legitimate, since pudding may be claimed as a British invention, and is certainly a characteristic dish of British cuisine…It seems that the ancestor of the term was the Latin word botellus, meaning sausage, from which came boudin and also pudding. Puddings in all their variety and glory may be seen as the multiple descendants of a Roman sausage. The Haggis, by its nature and the ways it is prepared, illuminates the connection.

In the Middle Ages the black pudding (blood sausages) was joined by the white pudding, which was also made in a sausage skin, or sometimes a stomach lining…White pudding was almost completely cereal in composition, usually containing a suet and breadcrumb mixture. It was variously enriched and flavoured, and there were sweet versions. In diverging from these origins English cooks found two paths which could be taken to advance pudding cookery. The first was to take advantage of the fact that by the 16th century many ordinary houses had small ovens built into the chimney breast, or at the side of the main bread oven where there was one. These ovens were not very hot. It was possible to bake a white pudding mixture or a cereal pottage slowly enough to suit it.

Everything changed a bit in the 1840s here in the US. Colonial times were tough, but by this point, the risk of starvation was no longer constantly hanging overhead. Colonists had adapted to the climate, created better ways to feed themselves, and trade routes were well-established. Winter starvation wasn’t a constant threat. Early settlers finally had a little more freedom in which to experiment with the ingredients they had on-hand, so they did.

Hasty Pudding and Indian Pudding

In some cases, like around the New England states (that’s Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island (and sometimes) Vermont), folks created a regional dish still beloved today. You may have heard of Hasty pudding or Indian pudding.

Hasty Pudding was first described in England around 1599, and appeared in numerous recipes from the American colonies throughout the 18th century. When Hasty Pudding came to America, the recipe changed to incorporate cornmeal, then also known as Indian meal, which was cheaper and more abundant than the English flour that the original recipe called for. Because of this substitution as well as the similarity between a native dish, Hasty Pudding became alternately known as Indian Pudding, though its origins were purely English. The recipe was also anything but hasty, since the pudding could take up to a few hours for colonists to cook!

Funny thing, Maryland isn’t even in the list of New England states. I guess it’s more about early settled areas than defined contemporary regions. My *new* home state, Pennsylvania, is considered a Mid-Atlantic (or Middle Atlantic) State. Even so, my husband heard about Indian Pudding through people chatting at work, which I find interesting.

Indian pudding might not be pretty, but few New England desserts can rival its claim to fame as the most comprehensive of our regional sweet dishes. It evolved out of an initial British culinary tradition, which was then enhanced by Native American influenced necessity, and finally, flavored with the fruits of New England commerce.

Aimee Tucker, Indian Pudding: History of a Classic New England Dessert, Yankee Magazine, February 2, 2021.

Its popularity held so much so that a small club at Harvard consumed vast quantities of the stuff in the late 1700s. On purpose.

On Sept. 1, 1795, 21 Harvard juniors gathered in a dorm room to found The Hasty Pudding Club. The club took its name from the traditional English dessert that was lugged across Harvard Yard in a giant cast-iron pot and dished out at their meetings. At a time when there were few social clubs on campus, the gatherings were a welcome respite for members, whose raucous mock trials against each other would evolve into the annual stage show produced today.

John Michael Baglione, Icons of entertainment Honored through the Years, The Harvard Gazette, January 30, 2018.

Hasty pudding wasn’t part of an elaborate prank. Its presence was something akin to necessity. Those kids were hungry.

At the turn of the 18th century, Harvard dining halls were notorious for serving unappetizing meals. Taking matters into their own hands, the Pudding’s founders mandated that “the members in alphabetical order shall provide a pot of hasty-pudding for every meeting.” And so it was that each meeting of the Club was heralded by the arrival of two undergraduates lugging an enormous cast iron pot…across Harvard Yard.

Hasty Pudding Club History, Hasty Pudding Institute of 1770, Accessed August 3, 2021.

Imagine that. Good thing dining halls, at least in many a college, have improved. Now, where were we? Okay, so way back when, those early colonists boiled all the things. But as the years went on, colonists had supplies and stable food sources. They didn’t need to eat everything in boiled form, so pudding continued to evolve, in no small part thanks to Alfred Bird.

You see, Alfred Bird (1811 – 15 December 1878) invented egg-free custard powder (and baking soda) as a solution to his wife’s egg and yeast allergies (what a guy!).

“Bird’s” is the brand name for the original custard powder. It was formulated by Alfred Bird back in 1837 because his wife was allergic to eggs (the key ingredient in traditionally-prepared egg custard). What it is not is: dried, powdered custard. What it is, is: a mixture of cornstarch, salt and flavorings (predominately vanilla) which thicken to form a custard-like sauce when mixed with sugar and milk and heated.

There is just enough coloring added (food-safe annatto) to give the custard the appearance of being full of eggs. By adjusting the amount of milk, the consistency of the custard can be adjusted to make a sauce, a spoon dessert, a pastry cream or pie filling. It’s so popular in the UK that the general use of the word “custard” more-often-than-not implies “Bird’s.”

When Alfred turned to commercial production, people, especially food-stretching pioneers, embraced his custard powder as a way to make puddings while on the trail. Pioneers craved food variety after the monotony of endless walking, and pudding would have pepped up the family. Nothing boosts your spirits more than dessert (okay, and coffee).

The distinction between European custard and American pudding became muddled sometime in the 1840s. At that time in America, traditional boiled puddings were no longer necessary to feed the average family. There was plenty of food. This also happened to be the same time when Alfred Bird, an English chemist, introduced custard powder as an alternative to egg thickeners.

It wasn’t long before Americans began using custard powder and other cornstarch derivatives as thickeners for custard-type desserts. This proved quite useful for overlander (conestoga wagon) cooks who did not have ready access to a reliable supply of fresh eggs.

Bird’s Original Custard Powder is still available today. Click on the image to the left to head to Amazon, click on this link to head to eBay, or go shop local if you can. Ethnic grocery stores, gourmet grocery stores, Cost Plus World Market, and even some grocery stores carry Bird’s Original Custard Powder in their international section. Neat!

Isn’t that interesting? I’m sure some of you have great memories to share surrounding Bird’s custard. But, these aren’t the only regionally-known puddings.

Banana Pudding Wasn’t Always Southern

Banana pudding is often linked to the south, but it appears to have gotten its start in other, decidedly NOT so southern states. Who would have thunk it? Where did banana pudding originate? You’ll never guess.

Yet the dessert’s link to the American South is less clear, particularly given that banana pudding’s earliest recipes came from Massachusetts (where Good Housekeeping was based) and central Illinois. While theories abound, I and others believe the connection lies in the dessert’s ability to feed a crowd and the region’s penchant for large gatherings. Whether making banana pudding for two or 20, the time and level of effort required is roughly the same. And when served chilled, it offers a cool, sweet respite from the sweltering heat Southern states can experience.

That makes a lot of sense. Southerners may pride themselves on the dish, but banana pudding’s roots dig deep and cover plenty of ground. Unfortunately, the bananas we know are in trouble. Say it ain’t so!

Grab a banana, and you’re likely reaching for a bunch of Cavendish bananas. They are the most common variety here in the US. But back in the late 1800s, Gros. Michel, or “Big Mike” bananas were the thing, and would remain that way until the 1950s and 1960s, at least until the Panama disease fungus almost wiped them out. While the bananas are still around, they are available on a much, much smaller scale.

Cavendish bananas, although lacking in flavor compared to other varieties, were so simple to farm, and replaced the Gros. Michel bananas. The entire banana growing and shipping cycle has revolved around this single strain for decades.

When a farmer wants a new banana plant, he or she removes a part of an existing plant (either a side shoot, called a “sucker,” or an underground root-like structure called a “corm”) and puts it in the ground. In time, it will develop into its own genetically identical plant. Without sexual reproduction — a grain of pollen fertilizing an egg, as occurs with most other fruit species — there’s no random variation among plants that growers need to worry about. Every banana you’ve ever eaten is a clone.

Joseph Stromberg, The Improbable Rise of the Banana, America’s Most Popular Fruit, Vox, March 29, 2016.

You don’t have to specialize in genetics to understand that having the exact same of a living thing is not a good idea. It makes it that much easier for diseases or pests to wipe them out. You’ve maybe heard of Tropical Race 4 (TR4), or Panama Disease, and its resistance to the typical treatments. Although experts don’t necessarily believe it will end the type of banana we all know and love, Tropical Race 4 (TR4), or Panama Disease, is a cause for concern: Banana prices will rise. As someone who buys a ridiculous amount of bananas a week, that’s very bad news, indeed.

As a former Hoosier (someone from Indiana), I should point out that banana pudding did make the rotation at various pitch-in dinners. I remember my own grandma making banana pudding sometimes too, though I must confess it was never my favorite thing, at least, not until I made my own from scratch (which is so often the way it goes, right?).

Persimmon Pudding

Since we are talking regional puddings, I can’t forget persimmon pudding. Persimmon pudding is an Indiana thing, but spending ages 5-19 as a northwest Indiana Hoosier, I had never had it (or had even heard of it), until I was well into my adulthood and traveling around southern Indiana for Little Indiana.

Persimmons were (and are) a big deal in those parts, with plenty of places offering up persimmon pudding or persimmon ice cream (homemade persimmon ice cream is heaven and was a favorite of mine whenever I visited Nashville, Indiana). Persimmon pudding is more like the baked puddings we’ve talked about.

If you find yourself in Lawrence County, or more specifically, Mitchel, Indiana, then you might want to visit the Persimmon Festival. Mitchell is the birthplace of Virgil “Gus” Grissom, so expect related events. But when it comes to the persimmon, the Persimmon Pudding and Persimmon Novelty Dessert Contest are pretty big stuff.

The pudding must be a 4×4 inch piece on a plain 8 or 9 inch white paper plate, covered with either wax paper or plastic wrap: with no topping of any kind. We do not need the recipe at the time of the judging.

Novelty dessert can be any- thing except cookies, making sure that persimmon pulp is one of the main & largest ingredients in the recipe. The recipe for the novelty dessert is needed at the time of judging and should include the name of the recipe and the name of the entrant on the back of the card. All recipes need to be on recipe cards, recipes written on sheets of paper will not be accepted. Rules are strictly enforced.

Scrolling through the list of winners from previous years, it’s fun to see the same names popping up a number of times. I bet there is a bit of stiff competition there, especially since first prize for the novelty dessert is $100 and first place for the persimmon pudding contest is $500. Back in the glory days of Little Indiana, I remember sending an email to find out if I could help judge. I did receive a response, but by the time they said I could fill in for someone, it was too late for me to figure out travel logistics. I never did make it to that Indiana county, which is a pity.

Anyway, wild American persimmons are the key to the perfect persimmon pudding, though there are plenty of Hoosiers who use Hachiya persimmons. American persimmons are said to have a stronger flavor than their Asian counterparts. Of course, the American persimmon has one more claim to fame, that of weather prediction.

Because of the American persimmon’s ability to grow almost anywhere in the contiguous United States, the tree and its fruits have integrated into local culture, including the central US region of the Ozarks. According to Ozark folklore, the shape of Persimmon seeds can actually predict the severity of winter in the area.

Patrick Bryers, a horticulture specialist at the University of Missouri, reports that a spoon-shaped seed indicates a higher than average snowfall for winter, a knife shape signals colder than average temperatures, and a fork shape indicates warmer than average winters. There is no consensus about the accuracy of this prediction method, but countless blogs cite Persimmon seed predictions as an annual fun tradition shared among family and friends.

Persimmons are ripe when the fruit falls to the ground. For real. That’s probably the easiest fruit picking ever. According to Garden.eco, ripe persimmon pulp is nearly 34% fruit sugar. A ripe persimmon should feel soft and squishy. You will have to get to them before the animals do. I’ve heard that persimmons are sometimes nicknamed Possumwood because possums also love the things.

Ripe persimmon time begins in August and September and runs all the way through to January or February for Southern Indiana folks. Some people believe that a persimmon isn’t ripe until it’s experienced a frost, but that’s more folklore than truth. If you pick a persimmon off the tree, well, I’ve read that that’s something you’ll never try again.

It’s not uncommon for area orchards to buy persimmon from local folks and process the stuff into pulp. This is a small scale type of production, but you can find frozen persimmon pulp at many an Indiana orchard. Just ask and ask early. But watch out if you plan to overindulge on a super scale:

A warning to those tempted to over-indulge in persimmon fruit: the tannin in the unripened fruit can combine with other stomach contents to form what is called a phytobezoar, a sort of gooey food ball that can become quite hard. One patient had eaten over two pounds of persimmons every day for over 40 years. Surgery is often required to remove bezoars, but a recent study indicated Coca-Cola could be used to chemically shrink or eliminate the diospyrobezoar. There is very little risk to those infrequently eating ripe persimmons.

The Fruit Of The Gods From An Indiana Tree?, Purdue University Forestry and Natural Resources, Accessed August 4, 2021.

You know how they say the best time to plant a tree is yesterday? That advice especially holds true when it comes to the persimmon. American persimmons can take a full ten years to bear fruit. Better get crackin’.

Dessert Pudding as We Know It Today

Regional puddings are great, but what about the type of smooth dessert pudding we are all familiar with? When did chocolate pudding became a thing?

Chocolate Pudding

Now, if you are wondering when chocolate pudding came about, do a little Googling, surf a few websites, and you will find two main conflicting answers. Sort of. You see, while some sources may point to chocolate pudding as being “invented” sometime around 1730, others point to the 1800s, and the time frame depends on the kind of pudding you are talking about.

Remember the whole “pudding in the UK versus pudding in the US” kerfuffle regarding what the word “pudding” means? Well, the 1730 chocolate pudding invention date correlates to something closer to a steamed pudding, while the 19th century date aligns with what we in the US actually term chocolate pudding. You know, that smooth, creamy, delightful bowl of deliciousness.

Why 1730? Well, according to ThoughtCo, “Cocoa beans had dropped in price from $3 per pound to a price within the financial reach of those other than the very wealthy.” People from various walks of life, and not just the upper crust, could afford chocolate.

General Foods (Jell-O) had dabbled in chocolate before, with a chocolate gelatin in 1927. Although chocolate gelatin was discontinued the same year, a chocolate instant pudding mix appeared in 1936, and lunchboxes were never the same again. Instant chocolate pudding’s ensuing popularity resulted in a slew of other flavors.

All About Dessert Mousse

Mousse is French for “foam.” Do a little digging on the beginnings of mousse, like I did, and you will discover two things, but only ONE of them is true: 1. the first mousses were savory and made with meat or fish, and 2. Artist Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa invented chocolate mousse. Choice #1 would be correct.

The majority of websites mentioning chocolate mousse and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec share that the artist was its inventor. I managed to do a ton of research on Henri before discovering that all those trusted websites and resources have it wrong. Henri didn’t invent chocolate mousse. Let’s first take a look at the life of Henri, so you can see why people believe he invented chocolate mousse, before I tell you the REAL story.

Henri Mari Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa is NOT the Inventor of Chocolate Mousse

Born to an aristocratic family, the arts were typically something one invested in and artists were someone you handed money over to, not something an aristocrat would become, but there was much about the life of Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa (24 November 1864 – 9 September 1901) that was anything but typical.

After all, his parents were first cousins, with an ancestry resembling something closer to a telephone pole than a branching tree. Inbreeding was the norm in the Toulouse-Lautrec fam, with multiple generations REALLY keeping it in the family. Aristocrats, you know. It wasn’t uncommon. Henri’s parents divorced when he was elementary school-aged, and his father fell off the face of the Earth, at least as far as Henri was concerned.

This sport-loving family were likely at a loss when young Henri broke first a femur in one leg, and then another, within the span of a year, beginning when he was 13. His legs stopped growing, and other abnormalities surfaced, so say online resources everywhere.

While reports differ as to his final height, reports vary between 4’8″-5’1″ and his condition is assumed to be due to what is now termed Toulouse-Lautrec syndrome. Unless your parents are related, you aren’t going to end up with Toulouse-Lautrec syndrome, or pycnodysostosis (PYCD), a (recessive trait) genetic disease featuring brittle bones, a stature that rarely exceeds 4’1″, and abnormalities with your extremities. Needless to say, that affected Henri’s involvement in the sporting activities of the day. He took to drawing. No surprise there, as several men in his family (including his father) made their living as draftsmen.

But, what is a surprise is the way his artwork was encouraged. Aristocrats gave money to the arts, they didn’t become artists themselves. Still, Henri’s mother encouraged him. A family friend, René Princeteau, took him under his wing, offering up lessons. Henri next trained with Léon Bonnat in 1882 in Montmartre, before continuing his training with Fernand Cormon the next year. Henri enjoyed the area so much, it is reported that Henri rarely left this bustling, inspiring, and unique neighborhood.

During his brief artistic career, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec captured the lively and often sordid atmosphere of Montmartre’s late 19th-century dance halls, cabarets, and theaters. Recording the performances he viewed and the establishments he visited on a nightly basis, he functioned as artist and narrator: his paintings, drawings, prints, and posters expose the complexities of the quickly changing age in which he lived.

Between 1890 and 1900, Paris saw tremendous growth in its nightlife scene, with nearly 300 café-concerts serving women and men who drank, smoked, and fraternized in ways previously unpermitted to them in public.

In such prominent clubs as the Moulin Rouge and less reputable institutions like the Moulin de la Galette, aristocrats often rubbed shoulders with the working class. It was within these establishments that Lautrec found the subjects he would voraciously document over the next decade.

Henri had found his people and a place where he could mostly belong. They were his tribe. Henri was known for throwing dinner parties, some involved him cooking in front of his guests like some sort of performance art, while others featured unique ingredients or preparation. He wasn’t alone in that. Men of his social status enjoyed all things food.

Paris boasted 27,000 cafes and more drinking establishments than any other city in the world by the end of the 19th Century. . . . The construction of Les Halles (1851-54), the great food market in Paris, ensured that the freshest, finest, and most flavorful comestibles, whether delicate white asparagus from Argenteuil or exquisite Belon oysters from Brittany, were readily available to all who desired them and had the means to procure them.” Records do not reveal whether Les Halles could supply Lautrec with his more outré ingredients.

Source after excellent source pointed to Henri Toulouse-Lautrec as the inventor of chocolate mousse, it turns out that that wasn’t the case. While Henri didn’t invent chocolate mousse, he was known for dabbling in the kitchen.

During his life, though, he enjoyed fine food as much as drink, and he threw frequent raucous, impromptu dinner parties for his wide circle of friends. According to one of them, the Symbolist poet Paul Leclercq, “He was a great gourmand… He loved to talk about cooking and knew of many rare recipes for making the most standard dishes… Cooking a leg of lamb for seven hours or preparing a lobster à l’Américaine held no secrets for him.” Indeed, his reputation as a confident and outlandish chef was so established that another friend, the artist Edouard Vuillard, painted a portrait of him standing in front of his oven.

Alastair Sooke, How to cook like Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, BBC: Culture, July 28, 2014.

Henri submitted work under the pseudonym “Tréclau,” an anagram of “Lautrec,” in 1887. He didn’t use his pseudonym for long. By 1884 he was known in Montmartre. Commissions rolled in. Henri was known to celebrate with dinner parties. Oil on canvas may have been the way things were done, but Henri didn’t much care for confinement. When the Moulin Rouge cabaret opened in 1889 and desired posters, he accepted, when other artists of the day would likely have turned up their noses at such a thing. Henri embraced lithographs, creating hundreds of them during his lifetime.

Since he felt shunned by the elite society, Toulouse-Lautrec delved instead into the theatrical underbelly of Paris. There, amongst sex workers and performers, he was less conscious of his appearance and was creatively inspired by the bohemian surroundings. Some 150 of the artist’s drawings and paintings are of the women he met at brothels.

Margherita Cole, 6 Fascinating Facts About Post-Impressionist Pioneer Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, My Modern Met, December 3, 2019.

But for all his parties and a large network of friends (his family’s connections nor his mother’s sending of items from the family estate wouldn’t hurt one bit) that’s not to say that he accepted his lot easily. By all accounts, he did anything but. Henri was said to keep alcohol in his hollowed-out cane and was a big fan of absinthe. Thadée Natanson, publisher of avant-garde La Revue Blanche, once said of Toulouse-Lautrec’s drinking, “He does not give his moustache time to dry,” reads the Mary Anne’s France website.

Henri’s 1896 series, Elles, was the largest hit of the bunch. Au salon de la rue des Moulins (At the Salon), seen below, is considered a masterpiece in his Elles collection.

The appearance of Elles coincided with a growing deterioration in his physical and mental condition. Toulouse-Lautrec’s figure, even among the great human diversity found in Montmartre, remained unmistakable. His fully developed torso rested on dwarfish legs. Not quite five feet one inch tall, his size seemed further diminished because of his practice of associating with unusually tall men, such as his fellow students Maxime Dethomas and Louis Anquetin and his cousin and close friend Gabriel Tapié de Céleyran. His frequently ironic tone failed to mask a fundamental dislike of his physical appearance, and his letters contain many derogatory remarks about his body and references to an increasing number of ailments, including syphilis.

Drinking heavily in the late 1890s, when he reputedly helped popularize the cocktail, he suffered a mental collapse at the beginning of 1899. The immediate cause was the sudden, unexplained departure of his mother from Paris on January 3. He was always close to his family, particularly to his mother, who had always supported his ambitions; and he interpreted her leaving as a betrayal. The effect on his weakened system was severe, and he was committed shortly thereafter to a sanatorium in Neuilly-sur-Seine. This decision was made by the artist’s mother, against the advice of relatives and friends of the artist, in the hope of avoiding a scandal.

Henri stayed on at the sanitarium months after his release. His health further declined and he died in September 1901 at his mother’s estate. The cause? A combination of alcoholism and syphilis. The late nights, the drinking, the…extracurricular activities took their toll. His body gave out.

According to My Modern Met, “In less than 20 years, he created 275 watercolors, 363 posters, 737 canvased paintings, and 5,084 drawings.” Remember, his kind of art wasn’t accepted just anywhere. These were new ideas and, in some cases, new mediums. Even Henri’s own family felt uncomfortable, with an uncle of Henri’s reportedly setting fire to some of Henri’s canvases. But Henri’s lifelong friend was determined to keep Henri’s memory, and his art, alive.

Maurice Joyant would live for another thirty years and work harder than anyone else to preserve his friend’s memory. He wrote extensively about his relationship with Toulouse-Lautrec and staged retrospectives.

Entrusted by Toulouse-Lautrec’s parents as executor of his friend’s paintings, he would also convince the painter’s mother, the Countess Adele de Toulouse-Lautrec to create a museum to the artist, where works rejected by the salons of Paris, were proudly displayed.

S. Za., Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Iconic Photos, November 8, 2010.

Henri’s mother started the museum, the Musée Toulouse-Lautrec in Albi, France. The site of the former Bishop’s Palace of Albi Cathedra, the incredible building holds the largest permanent collection of his work, including all 31 of his posters, with more than 1000 pieces.

Thirty years after Henri’s death, in 1930, Maurice Joyant, Henri’s friend, the organizer of Henri’s first exposition, the man who urged Henri’s mother to open a museum to preserve her son’s art, as well as an art dealer, collected together Henri’s recipes and menus for a cookbook.

History for the reader-gastronome of the 21st century to be inspired according to the mood of the moment of Salmon, trout and cod cooked under the ashes (a recipe that the author tells us to have gathered from Schroder, seal hunter in Spitsbergen!), Porpoise fillet stew (inherited from Joyant from the Governor of French West Africa!), Port woodcock (from Jacques Loysel, from Château La Vallière in Touraine), Poule au riz -plat favorite of the Andalusian dancer Dona Micaela, an artificial rabbit pâté (without rabbit but made from veal cutlets marinated in spices) for which a doctor member of the Academy of Medicine would have delivered the recipe, or even de la Palombe roasted, signature dish of Countess Adèle, Henri’s mother.

Catherine Thenes, Toulouse-Lautrec’s Recipes, says Monsieur Momo, Du Bruit Cote Cuisine, February 14, 2005.

Henri may have been a fan of food, but he was not the inventor of mousse au chocolat. So, who did invent chocolate mousse? Let’s take a look below.

The REAL Inventor of Chocolate Mousse

pour servir les meilleurs tables, suivant les quatre saisons · Volume 4 – a 1755 recipe for Chocolate Mousse.

Now, if Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec didn’t invent chocolate mousse, who did? We do know that chocolate hit France with the arrival of the Spanish princess Anne of Austria to Louis XIII, way back in 1615. While history will likely never know the original source, as people seem to develop the same things around the same time in different places, recipes for various dessert mousses, frozen or unfrozen, did pop up in French cookbooks.

The earliest reference I can find, thanks to Jim Chevallier’s comment on the Joe Pastry website, was in Les soupers de la cour ou l’art de travailler toutes sortes d’alimens pour servir les meilleurs tables, suivant les quatre saisons, Volume 4 or (in English: Court dinners or the art of working all kinds of food to serve the best tables, according to the four seasons) from 1755. You can read Court Dinners in full for FREE here.

The cookbook, La Science du Maître d’Hôtel Confiseur or (in English) The Science of a Master Confectioner,

That recipe appears long before Henri was even born. If it made it into a cookbook then, who knows how old chocolate mousse really is? After all, people have been glugging down chocolate for centuries before that even. And, while foamy eggs were all the rage in the eighteen century in France, it’s hard to know if that was the true beginning, or when chocolate mousse was finally documented.

A Word about Custards

Pudding and mousse aren’t the only sweet or savory items with a long history. Picture it: The Middle Ages. A time of…custard?

Regional Custards

Bonet

Bonet is a wonderfully old fashioned dessert, a caramel custard that’s simple to make but impressive enough for a dinner party.

Diana Henry, Bonet Recipe, House & Garden, May 13, 2020.

What is bonet? The Great Italian Chefs website states, “Its name relates to the ‘curvy hat’ shape given by the traditional, truncated conical copper mould used to cook the dessert in a bain-marie.” Information about a bonet is tough to find. Even the House & Garden quote I referenced above had Bonet recipe with the tag “the best recipes you’ve never heard of.” I flipped through my Italian cookbooks hoping to find a recipe and more information, but not a single one included bonet.

Bonèt is a traditional Italian dessert that can be traced back to the 13th century. Rich, creamy, and soft, the dessert consists of amaretti cookies or hazelnut biscuits, eggs, cocoa powder, sugar, milk, and rum. The whole concoction is typically drizzled over with caramel before serving.

In some places, it’s made with chocolate, in others with hazelnut, while, for instance, in Carru, it’s made without any of those ingredients. The name of the dish means hat, referring to the original shape of this treat (round with a hole in the middle), but some say that it can also refer to the fact that bonèt is the last thing that is consumed for dinner, just like a hat is the last thing one puts on the head before leaving.

It looks as though some use rum, while others use Cognac. I’m sure there are more variations, but the point is to add in flavor. Some bonet are sprinkled with hazelnuts, others turn to crunched up amaretti cookies.

…At its most fundamental it’s a custard baked inside a caramel-lined mold – but not just any custard, one that has been buoyed by chocolate and pebbled with nutty crumbs of amaretti, all of it soused in a generous glug of booze. It can support additional flavorings as well – there are recipes including a few drops of espresso, or the grated rind of a lemon; some call for only milk and others for cream. A lone recipe even spices up the mix with cinnamon. The booze component ranges from dark rum to Amaretto, and occasionally seems to be forgotten entirely.

Playing Favorites with Bônet, The Traveler’s Lunchbox, January 22, 2006.

There must be all kinds of good memories associated with this regional dessert. Are you an Italy traveler? Do you have any fun memories, experiences, interesting tidbits, or recipes regarding bonet? I’d love to know more.

Pasticciotto Leccese

It sounds fancy, but pasticciotto (plural: pasticciotti) Leccese is simply: custard pie made with a shortcrust. A shortcrust is made with lots of butter, resulting in a crumbly crust. Unlike other pies, this one is usually eaten warm, and sometimes consumed for breakfast! I’m liking that idea. Pie for breakfast should be a thing. Other times, it may be saved and reheated for a dessert.

One Galatina pastry shop, Pasticceria Ascalone, claims to have created the original pastry…300 years ago.

This jewel box of a pastry shop is where (so legend has it) the pasticciotto was invented. The pasticciotto is a small oval shaped pastry made from short crust and filled with pastry cream. It is eaten throughout southern Puglia, but was born in Galatina. The story dates back to 1875 when Nicola Ascalone decided to use his leftover dough and pastry cream to fashion a mini pastry, since there wasn’t enough for a full sized cake. This small golden delicacy flew off the shelves and made his pastry shop so famous that it is still going strong 300 years later.

Elizabeth Minchilli, Pasticciotto at Pasticceria Ascalone (Puglia), Elizabeth Minchilli, February 5, 2018.

Imagine that! Three hundred years of pastry. From poking around online, it seems as though many areas boast their own take on the traditional pastry. From black cherries to lemon to olives, you have options depending on where you roam. One notable variation possesses ties to the United States.

Telenorba, January 23, 2014.

Pasticciotto is a typical dessert from the Salento area of Apulia, consisting of pastry filled with custard and baked in the oven. Angelo Bisconti, owner of Pasticceria Cheri in Campi Salentina, has come up with a variation that has a chocolate base and a filling made of a mixture of sugar, eggs, flour and cocoa.

It all happened in 2008, when Bisconti struggled to come up with a new, tempting pastry to offer his customers. He slowly refined the pasticciotto until he had exactly what he was looking for. But the new dessert still didn’t have a name: it was the morning of November 5, 2008 and the election of America’s first black president was front-page news; Bisconti decided to honor him by naming his new dessert after Obama.

It was a lucky idea: in the years since, Bisconti has been able increase production of pasticciotto Obama from 50 to 5,000 pieces a day, which also allowed him to open ten new positions at his shop.

Creative and clever. Chocolate pastry paired with chocolate custard sounds amazing. People now ask for Pasticciotto Obama or Obama since the dessert has spread throughout the region.

Pastel de Nata

When I was in 6th grade, I threw myself into my social studies class, partly because I enjoyed history and partly because I was in competition with another boy for the better grade on the weekly tests. It was just a walk by “look at my grade” kind of exchange, nothing formal, but acing those tests was fun. My mom quizzed me so much during the unit on explorers, that even today we remember “bouncing Balboa,” as a hint for what he discovered (first European to reach the Pacific Ocean). He wasn’t the only explorer we remember.

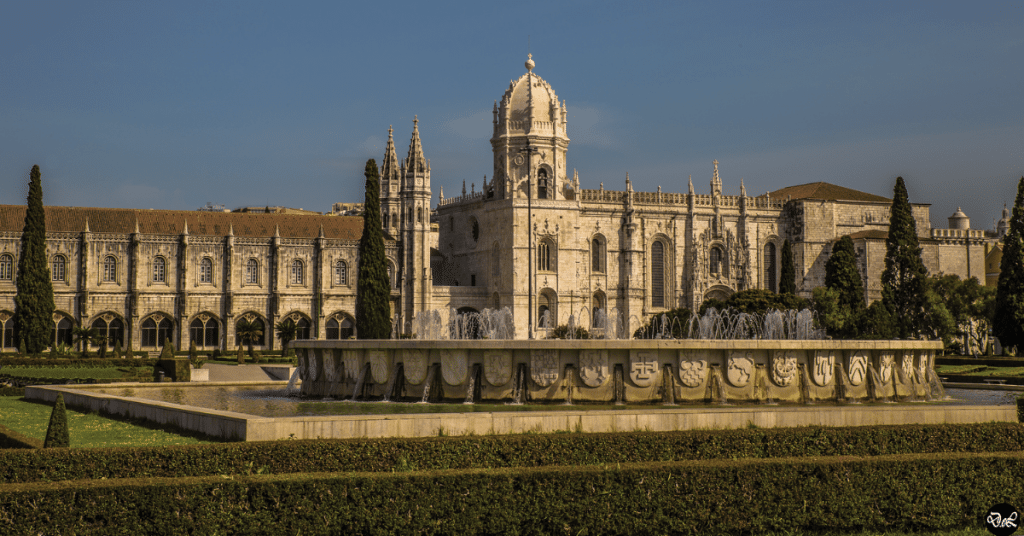

Vasco de Gama, the Portuguese explorer responsible for finding a sea route to India, was a part of the unit. As History.com says, “By the time Vasco da Gama returned from his first voyage to India in 1499, he had spent more than two years away from home, including 300 days at sea, and had traveled some 24,000 miles. Only 54 of his original crew of 170 men returned with him; the majority (including da Gama’s brother Paolo) had died of illnesses such as scurvy.” Vasco is also a part of the Mosteiro dos Jerónimos, at least, it’s where his tomb is located.

You see, before Vasco de Gama set sail to hunt for a sea route to India, he and his expedition prayed at a church. That church was torn down, and after planning and 100 years of construction (1501-1601), it became the site of the Mosteiro dos Jerónimos, a grand building meant to thank God for leading the explorers on the path to India. Extensive carvings of limestone and dazzling interiors showcase Portuguese Manueline architecture of the time.

With all that history, it’s no wonder the monastery was declared a national monument at the beginning of the 20th century and a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1983. As if that weren’t enough, there’s a very, shall we say delicious reason to visit.

Pasteis de nata, Pastels de Nata, or Portuguese custard tarts in plain English are a regional custard with a long, unique history. A crisp exterior pastry is filled with a sweet custard, and usually a touch of cinnamon. Visits to where Pasteis de Nata began, and the current bakery where the original recipe is made by hand and sold, top many a Portugal bucket list. As you probably guessed, it all started at Jerónimos Monastery.

The Pastel de Nata’s history dates back over 300 years, to Jerónimos Monastery in Belém, west of Lisbon. Today the monastery is a major tourist hotspot and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, but at the time it was a busy civil parish where, in the absence of laundry detergent, nuns and monks would use egg whites to starch their clothes. This process meant there were lots of egg yolks going spare, so to avoid these going to waste, they were instead used as a major ingredient in desserts.

The monks of the monastery soon created a secret recipe to perfect their custard tarts, which they began selling as a means of creating income to support the monastery. When the monastery closed in 1834, this recipe was then sold to the owners of the Fábrica de Pastéis de Belém, which opened in 1837, and is the most famous place to try custard tarts in all of Lisbon. Today, the recipe is still a closely guarded secret, and the tarts sold in this location are known as Pastéis de Belém. Just a three minute walk from the monastery, they’re a must try for anyone keen for a little bite of Portuguese history.

The bakery has a slight variation in years. But, as you’ll read below, they are sticking to the traditional recipe for Pasteis de Belem.

In 1837 we began making the original Pastéis de Belém, following an ancient recipe from the Mosteiro dos Jerónimos. That secret recipe is recreated every day in our bakery, by hand, using only traditional methods. Even today, the Pastéis de Belém offer the unique flavour of time-honoured Portuguese sweet making.

Pastéis de Belém, Pastéis de Belém, Accessed August 5, 2021.

That would be something to see (and taste). Give Fábrica de Pastéis de Belém a visit. Find them: Rua de Belém nº 84 a 92, 1300 – 085, Lisboa Portugal. Phone: +351 21 363 74 23.

Custard in the United States

Custard in the US is funny. Custard pies launched a new era in comedy: The pie fight. “The first thrown pie in the face dates to the Mack Sennett era, probably to a 1913 Fatty Arbuckle short called “A Noise From the Deep.” Pow, some pastry to the mug, and there it was: An innocuous dessert being used as a weapon, leaving stains of cherry, perhaps, but not of blood,” as written by The New York Times.

Silent film star Mabel Normand, the first to throw pies, and Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle were known for their pie-throwing skills. You can view a pie fight in the 1913 film The Ragtime Band above, starring Mabel in a time before custard pie fights became common. Although Roscoe “Fatty” doesn’t appear in that film, he was known for his pie-slinging prowess, throwing a pie in each hand in opposite directions on target. Look at some of his other work, especially The Cook, to view his hand-eye coordination prowess in action.

As Atlas Obscura notes, “For a time, Keystone Studios was a powerful studio, launching stars like Charlie Chaplin to prominence. But by the time the 1920s rolled around, people had grown tired of the custard-pie shtick. It wasn’t long before comedies were being advertised on their pie-less merits: one ad trumpeted that ‘a custard pie and a pretty girl or two in a bathing suit do not make a comedy.'” Bakeries created pies for the films of the day, some using special ingredients to better show up on black and white film, and most deviated away from the traditional custard pie into something a whole lot less edible, yet visually more impactful.

So, that’s how custard pies-to-the-face found their claim to fame. Stick to the non-movie version for a great-tasting, pie-throwin’ good time of a dessert. Let’s go further back for a look at a cake that’s sometimes filled with custard.

Boston Cream Pie

Was there ever a dessert that evoked more confusion than a Boston Cream Pie? Filled with custard, pudding, or pastry cream, made into two layers or one, made with a sponge cake or a butter cake, it seems there are more than a few variations on this one.

The Boston cream pie has been Massachusetts’ official state dessert since 1996. Even that official designation hasn’t helped, at least based on the number of websites (and even cookbooks) confusing BCP components. But, at the very least, the original Boston Cream Pie began with a pastry cream filling, a custard thickened with cornstarch.

The Omni Parker House, then simply Parker House Hotel, is credited with the creation of the Boston Cream Pie. You may recall the Parker House Hotel as having another, equally important, claim to fame: Brownies. Do read all about that. Of course, there is more to say on the subject of the Boston Cream Pie.

That’s a Tasty History

The next time you spoon into a pudding, make a mousse, or crave a custard, you’re digging into a lengthy and varied history. I guess these simple dishes aren’t so simple after all. History doesn’t have to be boring—and the histories behind those three certainly prove it.

Related Resources:

Leave a Reply