Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, I may receive compensation at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support.

Pound cake began with a pound of each ingredient: Eggs, flour, butter, and sugar. People then as now played around with recipes, increasing and decreasing ingredients, as they do. I don’t mean recently, either. Back in the 1800s people were already futzing with the recipe. I can tell you all about baking pound cake, but I tell ya what: Finding out when pound cake first appeared has been tricky.

Normally on Little Indiana Bakes, I share the history of a particular food and go off from there. This time, I’ll be sharing with you the stories of multiple cookbook authors who were the first to include recipes for pound cake in their cookbooks. You’ll learn about them and view the original recipe as written by each woman. Neat, eh? I’ll link to their cookbooks in their updated forms below (they will be affiliate links, so if you make a purchase, I will receive a small percentage back at no extra cost to you).

Anyway, the best I can go off of are from the inside of the old cookbooks. Thanks to Project Gutenberg, and other online sources, the entirety of these fabulous old cookbooks can be read (and searched!) online for free. With this method, I have found the proof of pound cake recipes in some of America’s earliest cookbooks, and shared them with you below. Of course, if you need new, more modern cookbooks with pound cake recipes, I have that too.

- Timeline of Pound Cake Recipes

- Hanna Glasse and The Art of Cookery Plain and Easy

- Susannah Carter: The Frugal Housewife

- Amelia Simmons: American Cookery

- Mary Randolph: The Virginia Housewife

- Eliza Acton: Modern Cookery for Private Families

- Malinda Russell: A Domestic Cook Book

- What Mrs. Fisher Knows about Southern Cooking

- Pound Cakes in History

- Related Resources:

Timeline of Pound Cake Recipes

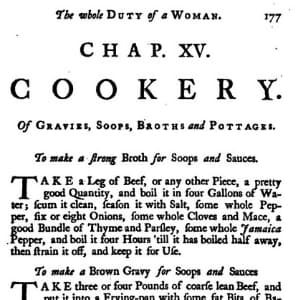

The beginning of pound cake, so far as we know, begins with Hanna Glasse and The Art of Cookery. Pound cake was a British invention, but didn’t appear in print until 1747. Let’s take a look at notable cookbooks and the pound cakes within them.

*Timeline References

- https://archive.org/details/TheArtOfCookery/page/n237 http://www.tonbridgehistory.org.uk/people/eliza-acton.htm

- https://blackamericaweb.com/2013/11/27/little-known-black-history-fact-abby-fisher/

- https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2010/12/the-mysterious-corruption-of-americas-first-cookbook/67592/

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/what-americas-first-cookbook-says-about-our-country-its-cuisine-180967809/

- https://lesleyannemcleod.blogspot.com/2013/09/the-female-instructor.html

- https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2020/fine-manuscript-and-printed-americana/carter-susannah-the-frugal-housewife-or-complete

- https://recipes.history.org/bibliography/

- https://ancestorsinaprons.com/2018/03/mary-randolph-women-wrote-cookbooks/

- http://thejemimacode.com/2010/03/10/abby-fisher-malinda-russell-accomplished-in-business/

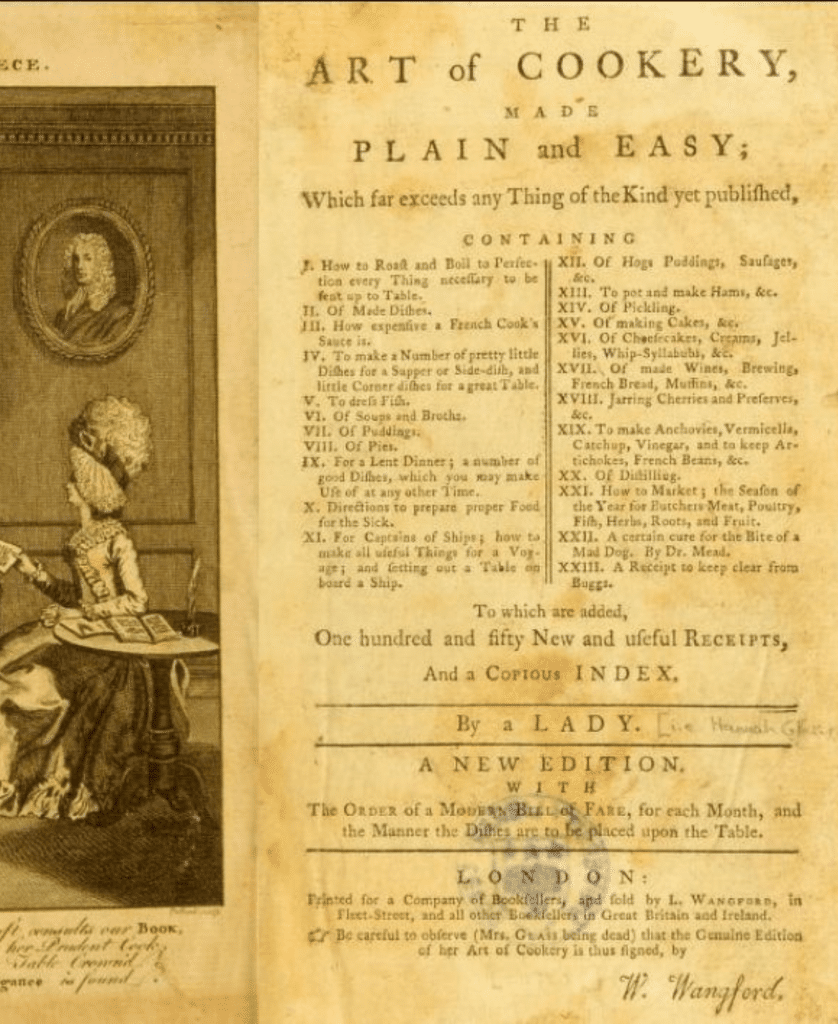

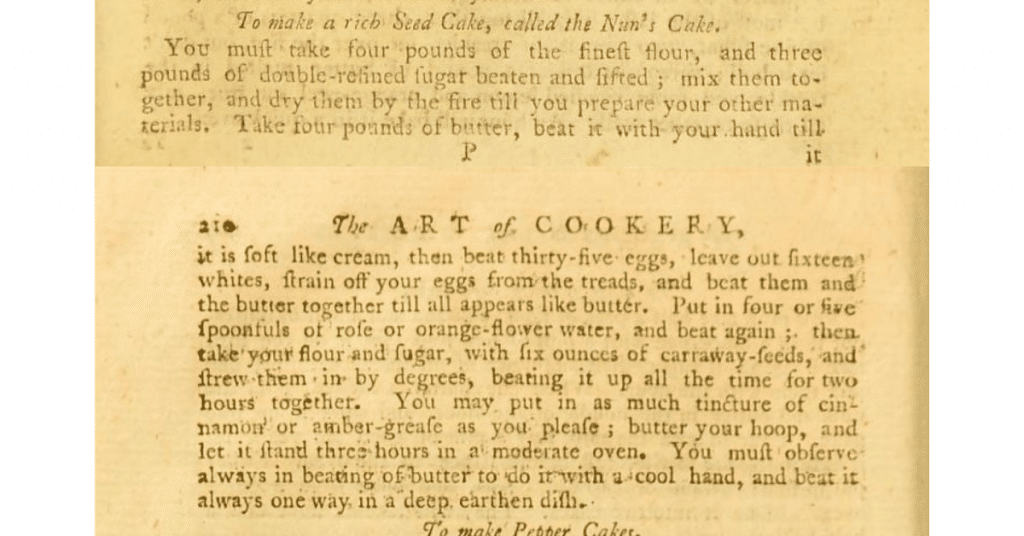

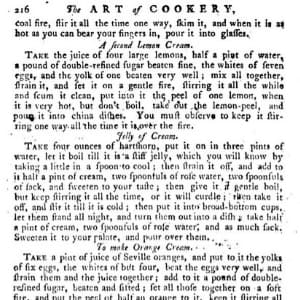

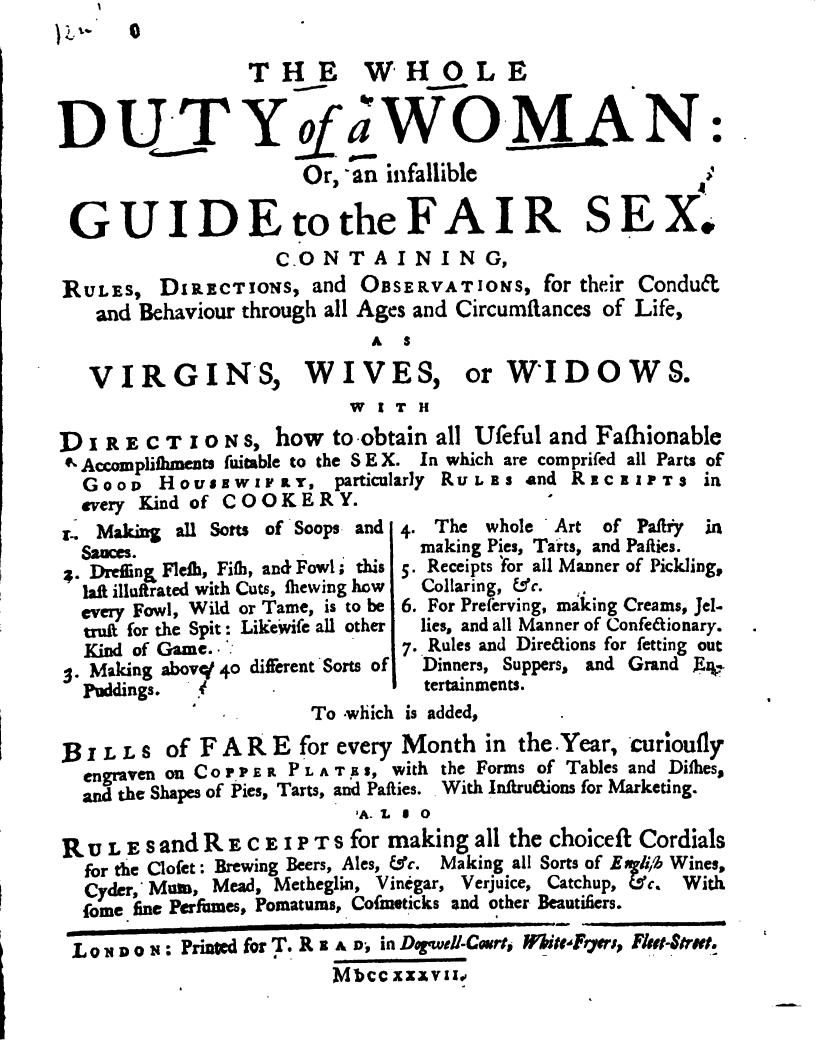

Hanna Glasse and The Art of Cookery Plain and Easy

I’ve seen whisperings of an older cookbook mentioning pound cake. After much searching, I have been unable to validate that claim. In my research, famed British author Hanna Glasse’s cookbook includes the first visual evidence in cookbook form that I can find.

“I believe I have attempted a branch of Cookery, which nobody has yet thought worth their while to write upon, but as I have both seen, and found, by experience, that the generality of servants are greatly wanting in that point, therefore I have taken upon me to instruct them in the best manner I am capable; and, I dare say, that every servant who can but read will be capable of making a tolerable good cook, and those who have the least notion of cookery can not miss of being very good ones.”

Hannah Glasse, The Art of Cookery Plain and Easy, Introduction (Page 2).

Hannah wrote the first HUGELY popular cookbook to a different type of audience. You see, back in Hannah’s time, cookbooks were for people already familiar with cooking. Male chefs (largely French) put out cookbooks, yes, but they lacked the details and clarity of Hannah’s work (in terms of other books of her time). These chef-authored books were for professionals, by professionals.

The historical landscape of the mid-18th century provided this perfect opportunity. With mass migration into the the cities of people looking for better paid work, a new and aspirational middle class burgeoned. Desperate to keep up with the Joneses, they had little trouble pursuing the correct educational course, dressing the part and doing up the house to match.

Putting impressive food on the table was, as it always seems to be, the perennial hitch. Without any knowledge of how to cook or instruct servants, and the only cookery books commercially available being written by grand chefs for grand chefs (often still the case with cookery books), they had little resource for serving up a meal for their guests that would be anything other than plain embarrassing.

Before we dig into Hannah’s cookbook, let’s take a moment to learn more about the author.

About Hannah Allgood Glasse

Hannah Allgood was born in London in 1708 to Isaac Allgood of Hexham and Irish widow Hannah Reynolds. Too bad Isaac Allgood was already married. The pair would have two more children together (who wouldn’t make it out of childhood). Isaac also had a son, Isaac, with his wife. Future cookbook author Hannah became a part of the Allgood household. Can. You. Imagine?

In 1713, Reynolds was “banished from Hexham,” though no one knows why. The duo moved in London. Reynolds was not involved in her daughter’s life and, in a future correspondence, author Hannah would refer to her mother as a “wicked wretch.” In 1714, a drunk Allgood signed papers giving all of his property holdings (which would include his land and coal mines) to Reynolds. Upon sobering up, he freaked out. They separated. The Allgoods worked to get their property back, but didn’t succeed until 1840. Reynolds walked away with a bit of money and an annual allowance.

Back to 1724. Hannah’s stepmother died, her father took ill, and sixteen-year-old Hannah was sent to London to live with her grandmother. By the end of summer, Hannah would secretly marry John Glasse, a thirty-year-old man. As the years passed, Hannah would birth 11 children (though some believe she had 10), five of whom would die in childhood.

Money Woes

Husband and wife worked for the 4th Earl of Donegall, where Hannah worked in the kitchen. Still, the Glasse family needed money. Finances were a constant burden, and her husband’s frequent failed business ideas weren’t helping.

Thus far there is nothing special or heroic about this headstrong young woman with her unsatisfactory husband and, soon enough, a large brood of children. What distinguishes Hannah is what she did to make up for John’s frequently inventive but always disastrous business ventures.

Hannah applied energy and imagination to a series of undertakings with admittedly mixed success. The foremost of these, and the enterprise for which she should be remembered, was her cookbook: ‘The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, Which far exceeds any Thing of the Kind ever yet Printed’. The first edition was published in 1747 under the sobriquet ‘A Lady’ and was an immediate success.

Let us for the moment gloss over the sadder parts of Hannah’s entrepreneurial history, the highly successful (until it was not) habit-making shop patronised by the Prince of Wales et al., the attempt at promoting Daffy’s Elixir as a panacea, the spells of bankruptcy and incarceration in debtors’ prison. Her business acumen definitely had holes in it. However, in creating her cookbook she showed true flair.

The Allgood letters help us reconstruct the story. Hannah writes to her Northumberland relatives announcing her intentions of making a book, asking for recipes, and soliciting subscriptions. A first publication like hers needed subscribers – a sort of crowd funding of its time – to succeed. Her family supported her as did others often from quite distinguished households.

Hanna Glasse decided to write a cookbook to help her family make money. “In 1747, the same year that Hannah’s husband John died, the book was published and she went on to partner with her eldest daughter Margaret to become a dressmaker in Tavistock Street in Covent Garden, London,” says DailyMail.

When The Art of Cookery was published, it was an instant success. Equally popular with ladies of the house and domestic cooks and servants, it would go on to be reprinted in no less than 26 editions – and is still available today.

“If I have not wrote in the high, polite style, I hope I shall be forgiven; for my intention is to instruct the lower sort, and therefore must treat them in their own way. For example: when I bid them lard a fowl, if I should bid with large lardoons; they would not know what I meant; but when I say they must lard with little pieces of bacon, they know what I mean.”

Hannah Glasse, The Art of Cookery Plain and Simple, Page i.

Her intended audience were “the lower sort,” as she termed them. It was meant to be a sort of manual to reduce the work the lady of the house had to do, by providing the servants with clear instructions.

A Guide for Servants

While this isn’t the only book to aid in the instruction of servants, it’s the first book to provide British recipes and aid to servants, with easier-to-follow instructions than other books at the time.

“Out went the bewildering text of former cookery books (“pass it off brown” became “fry it brown in some good butter”; “draw him with parsley” became “throw some parsley over him”). Out went French nonsense: no complicated patisserie that an ordinary cook could not hope to cook successfully.

Glasse took into account the limitations of the average middle-class kitchen: the small number of staff, the basic cooking equipment, limited funds. She cleverly engineered weights and measures instructions, making them foolproof.

In her famous recipe, To Roast a Hare (see opposite page), she suggests “as much thyme as will lie on a six-pence” – a clever means to measure without machinery.”

Too bad most servants couldn’t read. In many homes, the lady of the house had to read the cookbook recipe for her servants to follow. Other times, the lady had to pitch in and help with meal preparation. Anyone like me who reads cookbooks like book, books, appreciates a certain conversational style. Hannah’s cookbook is considered the first known cookbook to use this friendly approach to recipe sharing. It won’t read that way to you and I, of course. Hannah loves her commas.

Where periods would know go today, Hannah throws down a comma.

Plenty of Plagiarism

Eliza Smith’s The Compleat Housewife, 1727

Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery, 1747

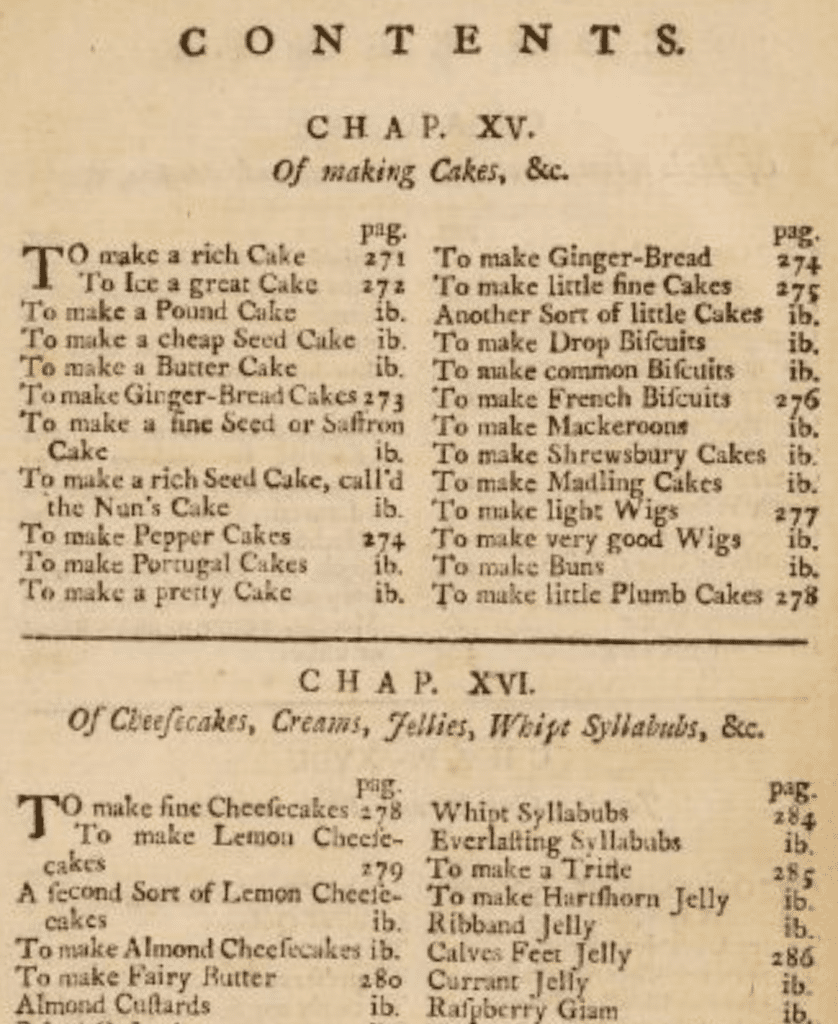

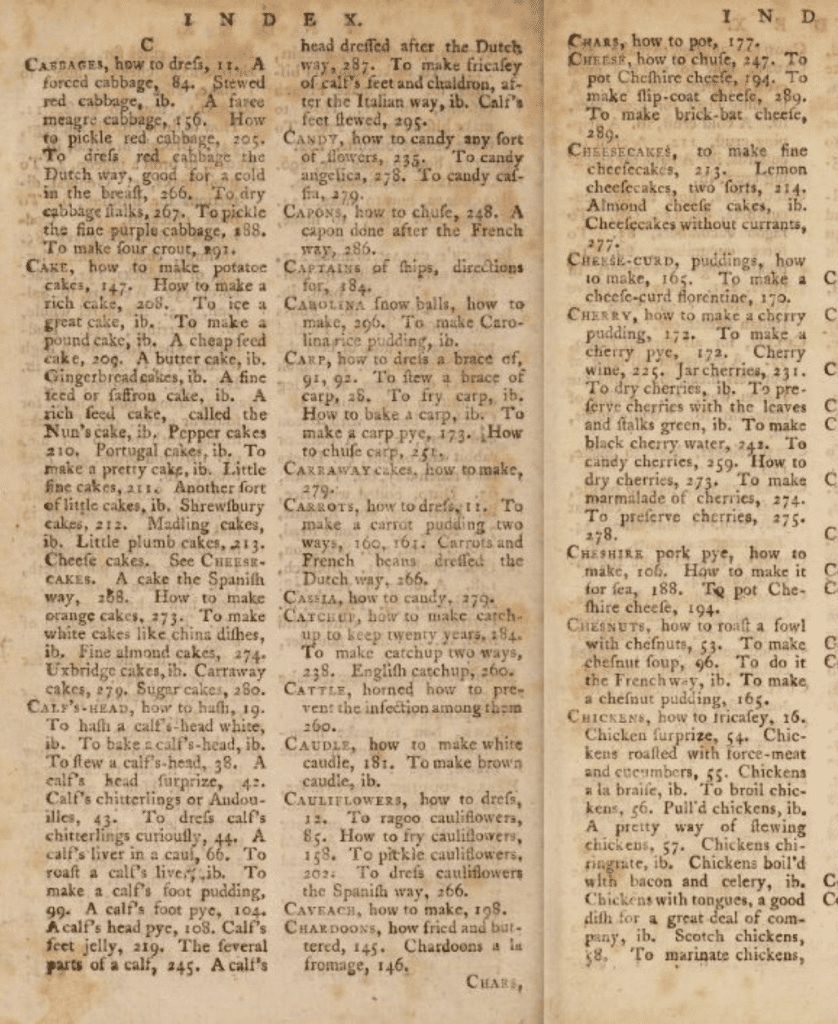

But, speaking of recipe sharing, Hannah Glasse is known for spreading Yorkshire pudding with The Art of Cookery Plain and Easy in 1747. Her book contained 972 recipes. Impressive, yes, but at the same time, Hanna lifted 342 of the recipes from other books of her time. This was by no means an uncommon practice at the time.

…Where the earlier cookbook writers used ridiculously formal language and operated under the assumption that the reader would merely pass instructions onto her cook, Hannah Glasse was writing for the middle-class woman who actually spent time in the kitchen.

Recall that the title of her book was The Art of Cookery made Plain and Easy: Hannah Glasse took those older recipes and made them plain and easy to understand and use. She rearranged the steps so they proceeded in a logical order. She included temperatures and cooking times down to the minute, which no one had thought to do before. All this, and she gave us curry and Welsh rarebit and Yorkshire pudding, too!…

You can see how The Art of Cookery copied The Compleat Housewife in the image above. Sharing recipes? Okay. Not changing the directions? Not okay. Not referencing original sources? Also, not okay. But, there weren’t plagiarism laws like there were today and…it was the way things were done.

In other cases, Hannah did rewrite the directions to take out unnecessary words (definitely not common in her day). As mentioned above, she was more precise in terms of temperature and cooking times too

Cookbooks for Non-Pros and Written by a Woman

Even with a bit of recipe “borrowing” (okay, a lot of recipe borrowing), Glasse changed the game. Her work proved that cookbooks didn’t have to cater to professionals and could still achieve success. It also showed that women were capable of such things, even if some people at the time disagreed. Some believed the work to be written by a man because it was “too good.”

‘Women can spin very well; but they cannot make a good book of cookery.’

Writer Samuel Johnson quoted as saying at a dinner party in publisher Charles Dilly’s home in the diary of writer James Boswell, 1778.

To learn more about that interesting conversation, do visit this article: Dr. Johnson takes on Hannah Glasse and Women Cookbook Authors by Patricia Bixler Reber (2014) on the Researching Food History blog.

Hannah Heads to Prison

With cookbook sales and reprints, Hannah and her family had some semblance of wealth. Unfortunately, their financial security wouldn’t last.

In 1747, the same year in which her book appeared, John Glasse died. In the same year also Hannah Glasse set herself up as a ‘habitmaker’ or dressmaker in Tavistock Street, Covent Garden, in partnership with her eldest daughter Margaret. It seems no records of this undertaking have survived.

In 1754 Hannah Glasse became personally bankrupt. Her stock was not auctioned after the bankruptcy, as it was all held in Margaret’s name. However on 29 October 1754 Hannah was forced to put her most prized asset, the copyright for The Art of Cookery, up for auction.

On 17 December 1754 the London Gazette stated that Hannah would be discharged from bankruptcy (issued with a certificate of conformity) on 11 January 1755. In the same year she and her brother Lancelot repaid the sum of £500 they had jointly borrowed of Sir Henry Bedingfeld two years before. She remained in her lodgings at Tavistock Street, but Hannah once again fell into dire financial difficulties and was consigned on the 22 June 1757 to Marshalsea debtor’s prison.

In July 1757 Hannah was transferred to Fleet Prison, where she remained, probably for several months.

Yes, Hannah lost her husband and opened a dressmaking shop to try to stay afloat. Instead, she lost everything, and had to auction away her cookbook’s copyright, a cookbook that had already been reprinted several times. She lost her only secure source of income.

Debtor’s Prisons

Wait, our hero goes to jail? A Debtor’s prison? It is as bad as it sounds.

You may remember Marshalsea Debtor’s Prison from Charles Dickens’ books. Charles’ father, John, was incarcerated for debt, along with his mother, sister, and siblings, as families often went together. John Dickens owed a baker £40 and 10 shillings. Charles remained behind, leaving school to work in a factory. He was 12 years old.

These jails were terrible places.

Debtor prisons charged for room and board. Yes, people who had nothing and were PUT IN PRISON, then had to come up with the money to pay for their room and board. “According to a 1729 parliamentary committee report, three hundred inmates starved to death within a three-month period,” shared an Amusing Planet article.

Debtor prisons had people pay off their debts either in labor or by someone coming up with the money to help them out. But they accrued more debt just by being there. It was a no-win situation. It’s kind of like how, during the Salem Witch Trials, one woman had her name cleared and could leave the jail, but she couldn’t afford to pay her shackle fee, so she ended up dying there.

Aside from food and rent, debtors were fined for all sort of offenses such as making too much noise, for fighting or cursing, smoking, stealing, defacing the staircase and so on.

Even if a prisoner managed to pay off his original debt, he may be unable to leave because of all the money indebted to the prison. When the Fleet Prison closed in 1842, two debtors were found to have been there for 30 years.

And Hannah Glasse, author of the first popular cookbook, a bereaved widow, a mother who (some believe) lost more children than would survive, and “a lady,” spent time in both prisons.

The only positive in this situation is this:

The book was merely attributed to ‘a lady’ and her authorship might never have been known had she not been forced to sell the copyright after she fell on hard times, was declared bankrupt and consigned to a debtor’s prison.

Tom Sykes, Meet Hannah Glasse, the World’s First Cookbook Author and Google Doodle Star, March 28, 2018.

Professed Cookery Mocks Art of Cookery

Not everyone loved Hannah’s cookbook. One woman, Ann H Cook, felt obliged to publisher her own, with a lengthy poem and an essay against The Art of Cookery. She called it Professed Cookery.

The Essay upon the Lady’s Art of Cookery is a violent onslaught upon Hannah Glasse’s Art of Cookery. According to the author of Professed Cookery anyone who followed Mrs. Glasse’s directions would infallibly be ruined both in digestion and pocket….Mrs. Cook is not content to attack Mrs. Glasse in prose. She is so much moved that she bursts into poetry:

If genealogy was understood

It’s all a Farce, her Title is not good;

Can Seed of Noble Blood or renown’d Squires

Teach Drudges to clean Spits and build up Fires?

The editor suggests that this means that Mrs. Cook knew that Mrs. Glasse was not a lady; the poetess waxes incoherent in her wrath, but I think she is making a different point. She is protesting against a lady claiming to know anything about cookery. She herself, the writer, makes no pretensions to being a lady, but she does know her work and her place, and she likes a lady who is a lady and knows hers.

I’m inclined to agree. While Ann was in an active legal battle over land with Hannah’s half-brother Isaac, I can kind of see how someone who is most definitely not a lady would perhaps consider this book the final straw. Kind of a “How dare she!” knee-jerk reaction. I mean, Ann examines page after page after page of recipes, pointing out their flaws and lack of economy or “vulgar extravagancy” as she terms it (when looking at Hannah’s veal, page 54).

But all that aside, The Art of Cookery wasn’t Hannah’s last book. She had two others to her name: The Servants’ Directory (1760) and The Compleat Confectioner (some say 1770), stealing some recipes here and there. But neither came close to the success of her first book.

The Rest of Hannah’s LIfe

No one knows how the last ten years of Hannah’s life unfolded. A brief line appeared in The Newcastle Courant announcing her death on September 1, 1770. She was sixty-two years old. But what of her descendants?

And if it seems as if Hannah Glasse’s story has an exclusively London bias, there is a curious postscript. For a document preserved at Nunwick Hall lists some of her surviving children, as of about 1767. Hannah the eldest was alive and unmarried, Catherine was twice widowed and had one son then living, Isaac Allgood Glasse was in Bombay, George who had joined the Royal Navy was lost at sea in 1761, and Margaret (chief partner in the habit making business) had died unmarried in Jamaica.

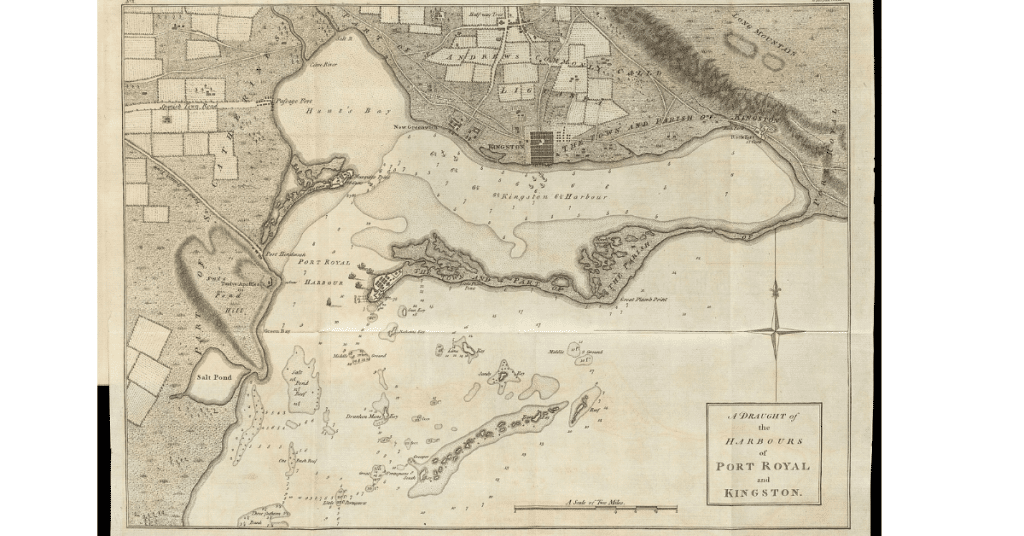

This raises intriguing questions about why she was there. Clearly a good living could be made in London if her mother’s client list were exploited, so had she gone to Jamaica alone or with a brother? I have not been able to find a burial record for her, nor any other trace of the Glasse family, except perhaps an Edward Glasse who was in Port Royal, and who buried a daughter called Margaret there in 1741. Was he perhaps an uncle?

Many of Hannah’s letters are saved and preserved by the Northumberland Council, so more is known about her life and the events of her time. Hannah wrote to her aunt on her father’s side. In it, she mentions that her book is doing well and has gone to press. She also includes a recipe to prevent the plague. Back then, plague was thought to spread by smell.

Take of rue, sage, mint, rosemary, wormwood and lavender a handful of each.

Infuse them together in a gallon of white wine vinegar. Put the whole into a stone pot closely covered up and pasted over the cover.

Set the pot, thus closed up, upon warm wood ashes for eight days, after which draw off (or strain through fine flannel) the liquid and put it into bottles well corked.

And into every quart bottle put a quarter of an ounce of camphor.

With this preparation wash your mouth and rub your loins and your temples every day.

Snuff a little up your nostrils when you go into the air and carry about you a bit of sponge dipped in the same in order to smell to upon all occasions, especially when you are near any place or person that is infected.

They write that four malefactors (who had robbed infected houses, and murdered the people during the course of the plague) owned, when they came to the gallows, that they had preserved themselves from the contagion by using the above medicine only, and that they went the whole time from house to house – without any fear of the distemper.

How tragic for the people who believed such a thing would work. Hooray for modern medicine and science to steer us in the right direction.

In the 75 years after her death, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy continued to be reissued 16 more times, including one Edinburgh edition (1781) and two American editions (1805 and 1812). The early editions of the book were published anonymously, with the only reference to authorship being “by a lady.” Only in the fourth edition did Glasse identify herself with the autograph of H. Glasse printed in facsimile on the beginning page of text and an elaborate advertisement printed in copperplate in a flyleaf opposite the title page presenting her as habit maker to the Princess of Wales. Eight years after her death, in the 1788 edition, Glasse’s full name was first listed as the author, as she had by then become commonly associated with the text.

Hannah Glasse, Encyclopedia.com, May 23, 2018.

People applaud Hannah Glasse for penning the first popular cookbook, changing the way women were regarded in terms of writing cookbooks, and for switching up how recipes were shared (and with whom). A Google Doodle commemorated her 310th birthday March 28, 2018.

Websites with Hannah Glasse Recipes

Hannah Glasse recipes are still made today. People update or use as is, just as it should be. Take a look at the websites below who offer up her relevant recipes.

- Colonial Williamsburg – A 1675 Vindaloo Roast Chicken, Bread for the History Lover

- David Fisco – Hannah Glasse’s Pound Cake: 1816

- A Food Rookie – Hannah Glasse – ‘To make gingerbread cakes’

- Historical living with Hvitr – Hannah Glasse’s chocolate pie

- Oakden – Pancakes | 1740 Recipe

- The Regency Cook – How to Make Tempting Chocolate Tarts – Hannah Glasse’s Way

- Silk Road Curry – Catchup to Keep Twenty-Years, Indian Curry Through Foreign Eyes #1: Hannah Glasse

- Revolutionary Pie – Orange Fool

Susannah Carter: The Frugal Housewife

While we know so much about Hannah Glasse, Susannah Carter is a mystery. We know she’s the second person to include a recipe for pound cake in a cookbook. Thanks to her title page, we also know Susannah was from Clerkenwell in London.

Somewhere around 1765, Susannah published The Frugal Housewife, or, Complete Woman Cook by Francis Newbery. Yes, Francis Newbery was the nephew to John Newbery of Newbery Medal fame. They were a family of publishers.

Originally published in the United Kingdom, Susannah Carter’s work was hugely successful, and after achieving best-seller status in that market, it was published for an American audience. Again, it was well-received, this time by colonial housewives. The first American printing actually included plates engraved by Paul Revere.

The Frugal Housewife Or, The Complete Women Cook, Andrews McMeel Publishing,

Yes, that Paul Revere of “The British are coming!” fame. It was the only cookbook published in the US from 1742 to 1796, states Andrews McMeel Publishing.

A Bit of Plagiarism

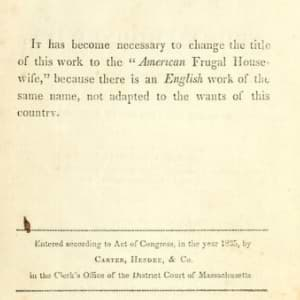

Amelia Simmon’s American Cookery (published in 1796) and, just like many cookbook authors of the day, she too pulled content from another source. In her case, she copied parts of The Frugal Housewife. The American version of The Frugal Housewife included a few additions, like pumpkin pie and recipes using maple.

Lydia Maria (Francis) Child, one amazing woman (and the author of the poem-turned-song Over the River and Through the Wood), wrote a book in the US with the same name in 1829. Go read about Lydia’s interesting life on the New England Historical Society website. Great stuff there.

Anyway. Susannah’s book was in print from 1829-1855. Some conjecture that the English version, Susannah’s version, achieved popularity due to title confusion. It makes sense. People do the same thing today, skimming off of what someone else built by rearranging popular blog or website names.

Websites with Susannah Carter Recipes

Unlike other early authors, people aren’t cooking up recipes from Susannah Carter as often. If you have made something, and wrote about it, please let me know and I’ll add it in.

- Early American Cooking – 1803 Breakfast Cakes

- Cape Gazette – An ode to old cookbooks: Gingerbread a mainstay of early American cookery (Traditional Gingersnaps)

Amelia Simmons: American Cookery

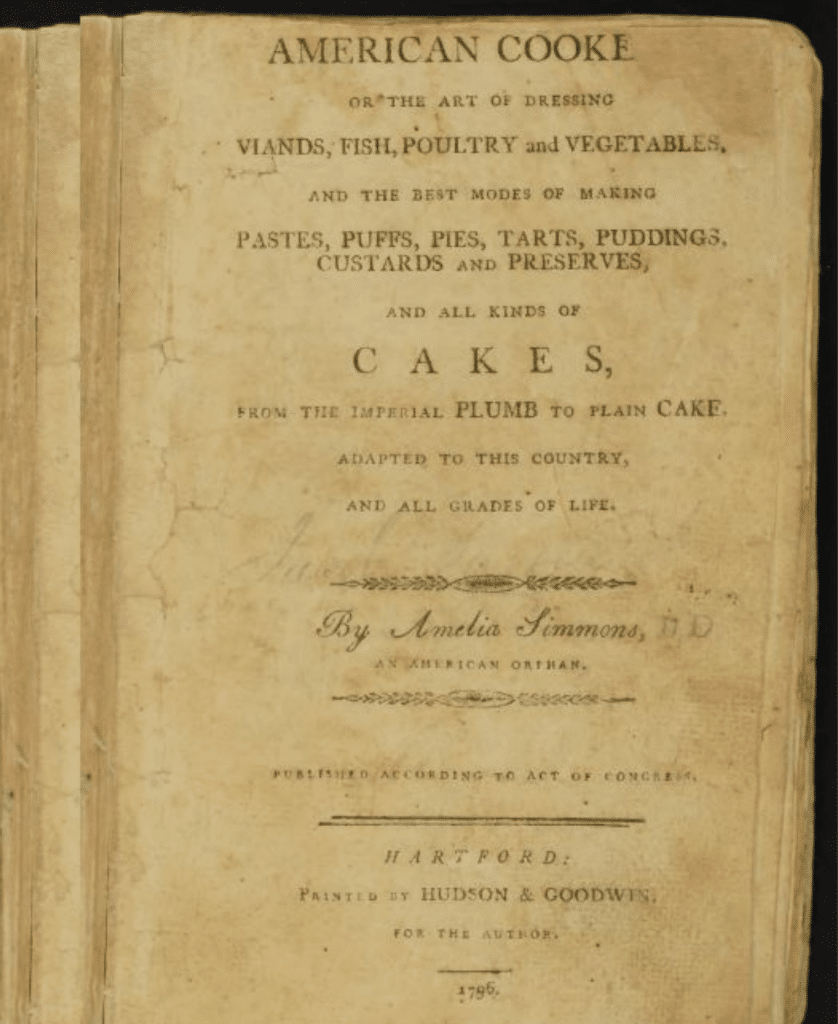

American Cookery, or the art of dressing viands, fish, poultry, and vegetables, and the best modes of making pastes, puffs, pies, tarts, puddings, custards, and preserves, and all kinds of cakes, from the imperial plum to plain cake: Adapted to this country, and all grades of life is the super short title of Amelia Simmons’ cookbook. It’s a part of the Books that Shaped America exhibit as chosen by the Library of Congress. Fancy.

This little cookbooks is also the first (known) cookbook published in the US and the first to use ingredients readily available here.

Unlike British cookbooks of the era, most of Simmons’s recipes centered on the use of corn meal—a staple of the American diet. Simmons used corn in a number of her dishes, including her “Hoe Cake” and “Indian Slapjacks.”

In addition to the insights provided by its choice of ingredients, American Cookery speaks to methods of early American food preparation. Most of Simmons’s recipes call for the production of food in large quantities, like a cake that required 2 pounds of butter and 15 eggs. Her syllabub (an alcoholic cider) called for sugar, nutmeg, and then milking a cow directly into the liquor.

One of Simmons’s innovations that made its way back to Europe was her use of leavening agents believed to be the precursors to modern baking powders. This revolutionary practice avoided the need to beat air into the dough or add yeast. Additionally, Simmons’s recipe for spruce beer fermented with molasses helped treat scurvy on long sailing voyages.

Although Amelia Simmons’ work is a scant fifty-page cookbook, tiny compared to the early books featuring hundreds and hundreds of pages, it proved useful to Americans who had larger cookbooks full of items they couldn’t use or methods not done in the US.

Amelia’s Practical Approach

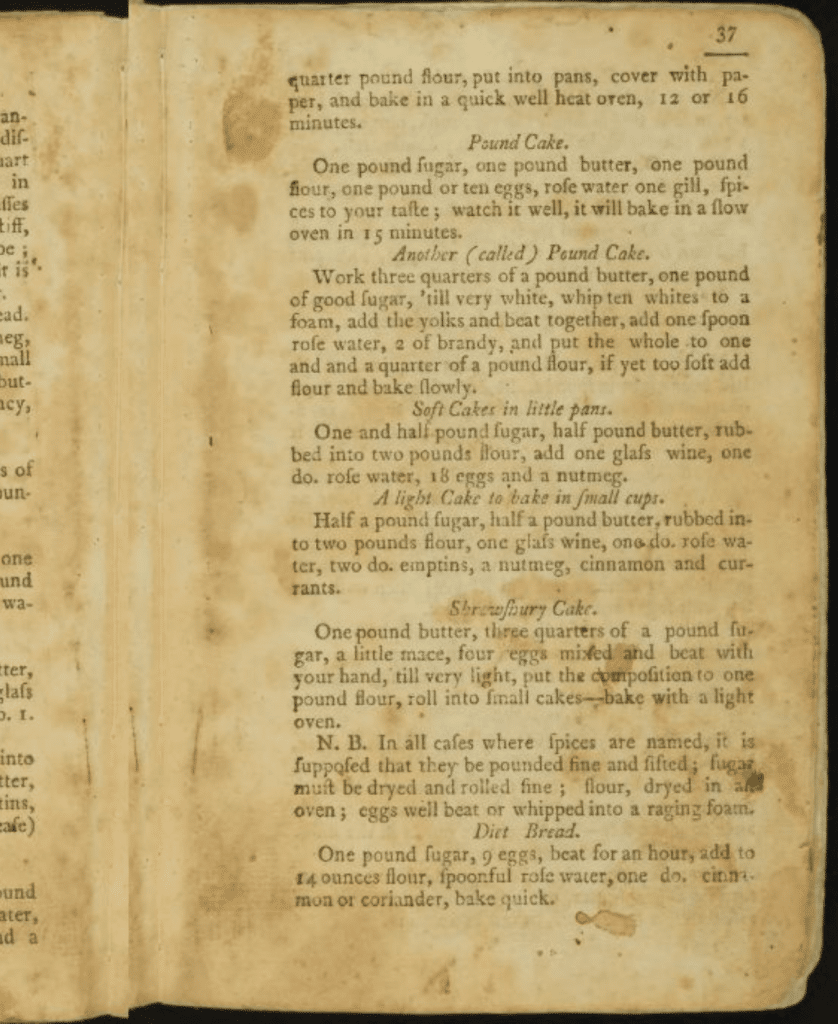

How interesting that this book, too, includes a recipe for pound cake.

With its new take on a practical topic, American Cookery caught the spirit of the times. It was the first cookbook to include foods like cranberry sauce, johnnycakes, Indian slapjacks, and custard-style pumpkin pie.

Moreover, Simmons had a keen understanding of the care that went into the construction of American household abundance. Behind every splendidly arrayed table lay the precise management of all the fruits and vegetables, meats and poultry, preserves and jellies, and cakes and pies that sustained the home and family—and American Cookery gave cooks and housewives tips for everyday cooking as well as occasions when the aim was to express greater gentility.

Simmons explained how to keep peas green until Christmas and how to dry peaches. She introduced culinary innovations like the use of the American chemical leavener pearlash, a precursor of baking soda. And she substituted American food terms for British ones—treacle became molasses, and cookies replaced small cakes or biscuits.

Above all, American Cookery proposed a cuisine combining British foods—long favored in the colonies and viewed as part of a refined style of life—with dishes made with local ingredients and associated with homegrown foodways. It asserted cultural independence from the mother country even as it offered a comfortable level of continuity with British cooking traditions.

That must have been huge, to flip through a cookbook, and realize you could make everything in it. That’s hard enough to do today. Amelia was ahead of her time.

Among her cookbook’s claims to originality is its surprisingly early use of a rudimentary baking powder, pearl ash (the chemical potassium carbonate, commonly called potash), to provide the carbon dioxide needed to make baked goods rise.

Potash had been used since ancient times in glass, soap, and other products. But neither pearl ash nor the other chemical leaveners which were eventually developed into baking powders are usually thought to have been used in cooking before 1830.

The English cookbooks Simmons probably had access to do not mention pearl ash. Simmons, and presumably other American cooks, therefore, seem to have been well ahead of their time with recipes like this, one of four in American Cookery calling for pearl ash…

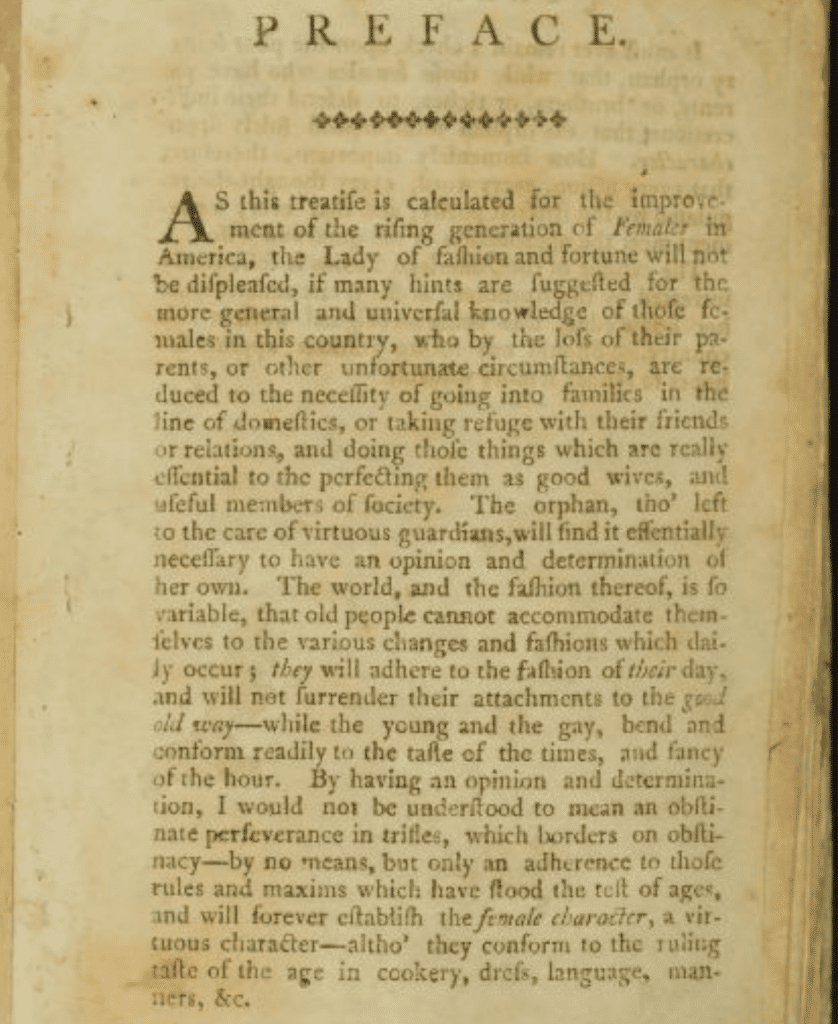

We know so little about Amelia Simmons. The only things we know are what she wrote in her book. She was an orphan, she cooked for others, and she didn’t know to write or read. As she says, she didn’t have “an education sufficient to prepare the work for the press.”

What else do we know? When Amelia’s book went into its second printing, she included a note regarding an (unknown) editor’s changes. Remember, she didn’t know how to read or write, so she had to trust that what she said was what someone wrote.

The most we get is in an advertisement for a subsequent printing of the cookbook, claiming that the author did not have the education to write the book herself, and had thus hired someone to record the receipts for her. This individual, the advertisement claims, took liberties which Simmons was unaware of until after the book’s publication. Thus, the reprint was not only to meet the extraordinary demand for the volume, but to also correct some of the mistakes.

Eric Colleary, Recipe: Pound Cake (1796), The American Table, August 1, 2012.

Amelia Call Out her “Helper”

Amelia Simmons is ticked off. She trusted the transcriber to do as requested—and she didn’t. So, she includes an advertisement to state why there are errors and why they are important. Her transcriber isn’t all bad:

Still, there’s no denying it: The unauthorized, rage-inducing market guide is the best part of American Cookery. Whoever the transcriber was, she was responsible for making the first recipe on the first page of the first American cookbook one for bacon smoked with corncobs—a fantastic choice. She decided that the same page would distinguish between stall-fed and grass-fed meats (she preferred stall-fed beef, and grass-fed mutton).

The transcriber was also a fine writer, her language a detailed, quirky, compelling delight. Because of her, we know that “veal bro’t to market in panniers, or in carriages, is to be preferred to that bro’t in bags, and flouncing on a sweaty horse.”

We know that salmon trout “are best when caught under a fall or cataract” (her description reads poignantly today, evoking a countryside filled with falls). We know that “bloated” fish were seasoned with salt and pepper before being dried in a chimney or the sun, which sounds dodgy but is nevertheless fun to think about.

As with so many cookbooks of the time, there are lists of other cookbook authors who stole her content. One “author” in particular changed the title in 1808 and passed off the work as her own. Keepin’ it classy.

Even so, American Cookery had thirteen editions published from 1796-1831. It, too, is available today. You can opt for a hardcopy below or read the free 1796 edition on Archive.org.

Websites with Amelia Simmons’ Recipes

What a surprising amount of recipes from Amelia Simmons getting whipped up in modern kitchens. Wouldn’t Amelia just love knowing that? Do send me your link if I missed you.

- The Heart of Cookery – Amelia Simmons’ Apple Pie

- The Historical Cooking Project – Guest Post: Amanda Moniz Makes Amelia Simmons’s 1796 Christmas Cookey

- Historical Society of Pennsylvania – A Pinch of History: Amelia Simmons’s Apple Pie

- History in the Making – Pompkin (Pumpkin Pie)

- Preservation Maryland – A Maryland Favorite With A Long History: Hasty Pudding

- Savoring the Past – 1796 Honey Gingerbread, Carrot Custard, Cranberry Sauce and Cranberry Tart, Early American Christmas Cookie

- Walbert’s Compendium – Early American Gingerbread Cakes

- World Turn’d Upside Down – What Is Election Cake? | Colonial Recipe | Amelia Simmons, 1796, Amelia Simmons’ 18th Century Pound Cake Recipe

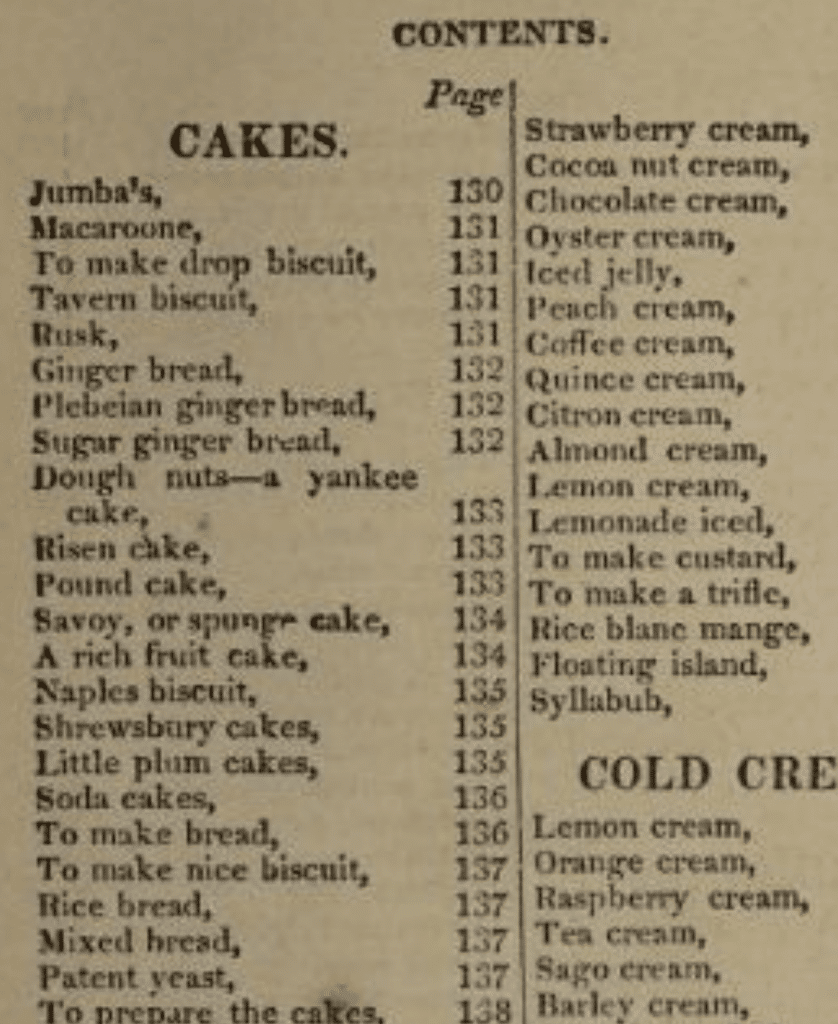

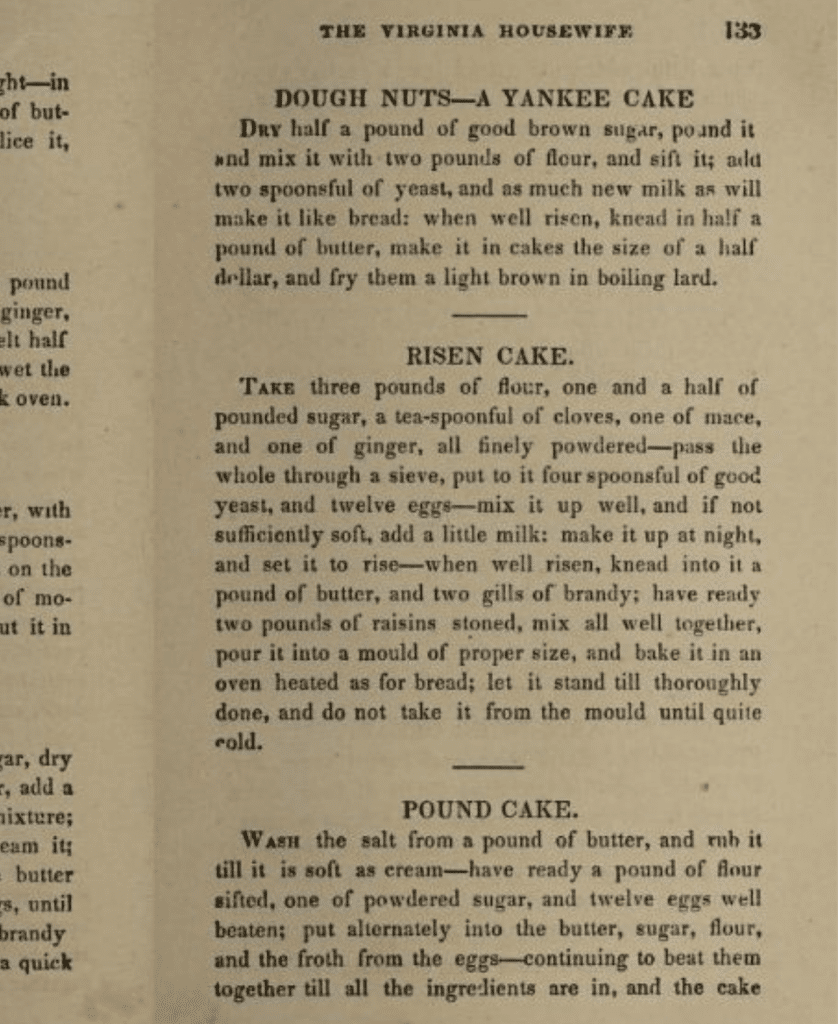

Mary Randolph: The Virginia Housewife

Who was a descendant of Pocahontas, Thomas Jefferson, and Mary Lee Fitzhugh (George Washington’s wife)? Yes, that would be Mary “Molly” Randolph, the author of The Virginia Housewife.

Mary Randolph is considered by food historians as one the best cooks to come out of an American kitchen. Her fried chicken recipe is the first to appear in an American cookbook. The use of fried cornmeal mush balls is the first recipe for what will eventually be called “hush puppies.”

Frank Clark, Fried Chickens, Colonial Williamsburg Historic Foodways “History is Served,” May 31, 2012.

But as prominent and well-to-do as her plantation- and slave-owning family may have been, they weren’t without their troubles. Debt, alcoholism, tempers, eccentricities, and even an infanticide trial surrounded Mary and her sibling’s lives.

Thomas Jefferson’s overseer had this to say: “The Randolphs were all strange people.” He would know. Mary’s father was raised by Thomas Jefferson’s family. Mary Randolph’s brother was the husband of Jefferson’s daughter, Martha. One way to describe Mary and her familiar situation would be well-connected.

Born in 1762 at her grandfather’s plantation in Chesterfield County, Va., Mary Randolph counted among her cousins Thomas Jefferson; Mary Lee Fitzhugh, the wife of George Washington Parke Custis who was the stepgrandson of George Washington; and David Meade Randolph, whom she married….

Bill Daley, Mary Randolph: Cookbook Star of 19th Century South, Chicago Tribune, September 18, 2013.

The Upper Crust

Mary was a member of the upper class, and a wealthy member at that. When Mary turned eighteen years old, she married David Meade Randolph (1760–1830), a well-known Federalist at the time — and also her first cousin, once removed.

David served as the US Marshal of Virginia under both George Washington and Samuel Adam beginning in 1795. The couple moved to Richmond, Virginia around 1798 and built Moldavia. Yes, they blended together their names for that one.

Mary’s hostess skills flourished. Like women in her social sphere, Mary had been privately educated at home so she would know how to run a home. The couple were known for throwing great dinner parties.

Although members of Thomas Jefferson’s extended family, Mary Randolph and her husband, David Meade Randolph, were among his most bitter political critics. Jefferson recommended David for the post of United States marshal for Virginia during Washington’s presidency, but his suspicion that Randolph packed a jury with Federalists led Jefferson to dismiss him in 1801.

Mary Randolph (Physiognotrace), The Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia,

Many historians believe David’s loud opposition lost him his job. Biting the hand that feeds you probably wasn’t the best idea, as the saying goes.

Job Loss and Status Change

That dismissal, coupled with a business recession, and a fall in tobacco prices, thrust the Randolph’s into financial difficulties, according to CooksInfo. They put Moldavia up for sale in 1802 and by 1805 had moved into a rental home. Even so, Mary and David had servants. They weren’t entirely destitute.

Within a few years, their financial situation had become critical, and Mary stepped in. She was determined to see her family taken care of, and took what was then a highly unorthodox step for an upper-class woman. In March, 1808, an advertisement appeared in The Richmond Virginia Gazette: “Mrs. RANDOLPH Has established a Boarding House in Cary Street, for the accommodation of Ladies and Gentlemen. She has comfortable chambers, and a stable well supplied for a few Horses.” Putting her abilities as a hostess together with her knowledge of good food and elegant presentation, Mary achieved instant success. The Randolphs’ boarding house was considered a place where “wit, humor, and good-fellowship prevailed, but excess rarely.”

Mary Carter Crump, Mary Randolph: A Chesterfield County Role Model for Women of the 19th Century, Chesterfield.gov, Accessed November 8, 2021.

In 1807, Mary and David opened a boardinghouse that would prosper for at least a decade, if not a little more.

Randolph was noted as a wit and also as a house-keeper. In her prosperous days she was called the queen by the guests who thronged her hospitable home,and when reverses came she showed she could be queen of the kitchen as well as the drawing-room, for she opened upon Cary Street a boarding house which achieved immediate success, and whose board became as famous as that at Moldavia had been.

Robert A. Lancaster, Historic Virginia Homes and Churches (page 154), 1915.

“In the same year that Mary opened her boarding house, David became an agent for Henry Heth in the operation of the Black Heth Coal Mines near Midlothian. David traveled to England and Wales to study their mining operations and to improve those in the Black Heth Mines. Always interested in turning a profit, David received patents in 1815 for his improvements in shipbuilding and candle making and in 1821 for improvements in drawing liquor. For his relative, George Washington Parke Curtis, he invented a special compound to waterproof Arlington, the Custis mansion,” says ArlingtonCemetery.net.

The Black Heth Coal Mines by Midlothian, Virginia were dangerous and prolific. Mary headed to Washington D.C. to live with one of her sons in 1819. In 1824 Mary published her first book, The Virginia Housewife, with a second edition the following year.

“Profusion is not elegance—a dinner justly calculated for the company, and consisting for the greater part of small articles, correctly prepared, and neatly served up, will make a much more pleasing alternative to the sight, and give far greater satisfaction to the appetite, than a table loaded with food, and from a multiplicity of dishes, unavoidably neglected in the preparation, and served up cold.”

What you just read above is so well ingrained in professionally trained chefs that the advice could have been written last year. The message is the same, the effect on food and guests remain the same as they were in 1824 when Mrs. Randolph wrote this wonderful book and the same good advice is practiced on a daily basis in professional restaurants and kitchens around the country whose aim is to serve quality food beautifully presented. More and bigger are not better; they are simply more and bigger.

It’s simple common sense, right? You don’t need to be a professional chef to understand that it isn’t about having a huge table of sucky dishes, but a small bit of the best of what you can do.

Cookbook Success

This book was a huge boon for the area. Her inclusion of pound cake shows it maintains its status as a popular and worthy item for the dining room table. I mean, if it made it onto her table, and she was choosy about the things she served, then it would have been welcomed anywhere.

Her book reflects the cooking of the American south at the time, recording everything from beaten biscuits to okra to catfish, with the base still noticeably British. And, there are many European recipes as well, because it was intended for those in wealthy households like hers that knew far more cooking than just “down-home” cooking.

Her book also puts paid to a number of theories about the period. For instance, she features tomatoes in no less than 17 of her recipes, showing that tomatoes were in fact in use in the early 1800s in America, despite the many food writers who believe otherwise.

The Mystery Grave at Arlington National Cemetery

Mary was hard at work on her third edition of The Virginia House-Wife when she died in 1828. She was buried on the grounds of her husband’s cousin’s home, George Washington Parke Custis, the adopted infant son of George Washington from Martha Washington’s first marriage. The property would later became the Arlington National Cemetery (Section 45).

Her grave had gone unnoticed until 1920s renovations began on the home, making Mary something of a mystery. Who was this non-military member buried here? But no one outside the family knew who Mary Randolph was or how she had ended up at Arlington National Cemetery.

Some of her great-grandchildren are living today, and have come forward to tell about the family; of her children and grandchildren, and how she came to be buried on the front lawn of Arlington House Estate. The oft misunderstood words carved upon the century-old marble slab above her grave, telling that she died “a victim to maternal love and duty,” are no longer an enigma.

“As a tribute of filial gratitude” that monument, “dedicated to her exalted virtues by her youngest son,” was erected by Burwell Starke Randolph, born 1800 and died 1854. As a midshipman in the United States Navy the unfortunate young man fell from a mast aboard ship and crippled himself for life by breaking both hips. The tradition among Mary Randolph’s descendants is that the devotion and care she lavished upon that cripple son broke down her own health and hastened her death.

In the memory of Mrs. Mary Randolph,

Mary Carter Crump, Mary Randolph: A Chesterfield County Role Model for Women of the 19th Century, Chesterfield.gov, Accessed November 9, 2021.

Her intrinsic worth needs no eulogium.

The deceased was born the 9th of August, 1762 at Amphill near Richmond, Virginia

And died the 23rd of January 1828

In Washington City a victim to maternal love and duty.

As a tribute of filial gratitude this monument is dedicated to her exhaulted (sic) virtue by her youngest son

The mystery of Mary Randolph had ended. As for how she ended up on the property, that’s easy. Mount Vernon.org states, “During the Civil War, Arlington House was captured by Union troops and the grounds turned into a cemetery, which it remains today as Arlington National Cemetery.” NPS shares that the brick wall’s purpose was to keep cattle away.

Mary’s influential housekeeping book The Virginia House-Wife (1824) went through many editions until the 1860s. Randolph tried to improve women’s lives by limiting the time they had to spend in their kitchens. The Virginia House-Wife included many inexpensive ingredients that anyone could purchase to make impressive meals. Besides popularizing the use of more than 40 vegetables, Randolph’s book also introduced to the southern public dishes from abroad, such as gazpacho.

Mary Randolph still makes the list of “top cooks” in history with her practical advice. From high society to business owner and cookbook author, she would have been one unusual woman in her day. Find her cookbook below in various reprints by various publishers or read it in full online for free.

There is even a version sort of updated for today’s cook. Every recipe in the original has not been updated. The authors considered their idea of a modern cook, and tweaked the recipes to match.

Websites with Mary Randolph recipes

Recipes from Mary Randolph’s cookbook are abundant. Take a look at all the sites featuring her “receipts” below. Did I miss anyone?

- The American Table – Recipe: Scolloped Tomatoes (1838)

- Chef Lindsey Farr – Mary Randolph’s Sweet Potato Pie

- Comfortably Hungry – Mary Randolph’s ‘Barbecue’ Shote

- Colonial Williamsburg – Fried Chicken, How to Make Potato Balls

- Cooking Mary Randolph – Website to devoted to Mary Randolph Recipes.

- Manuscript Cookbooks Survey – Bread as Mary Randolph Made It

- Metropolitan College Gastronomy Blog – Cookbooks & History: Apple Fritters

- The Shop Monticello – Crispy Pickled Green Beans with Mary Randolph’s Pepper Vinegar

- The Silk Road Gourmet – Indian Curry Through Foreign Eyes #2: Mary Randolph

- The Virginia Housewife Project –Website featuring recipes of Mary Randolph

- The Virginian-Pilot – How to Make a Delightful Oyster Catsup

Eliza Acton: Modern Cookery for Private Families

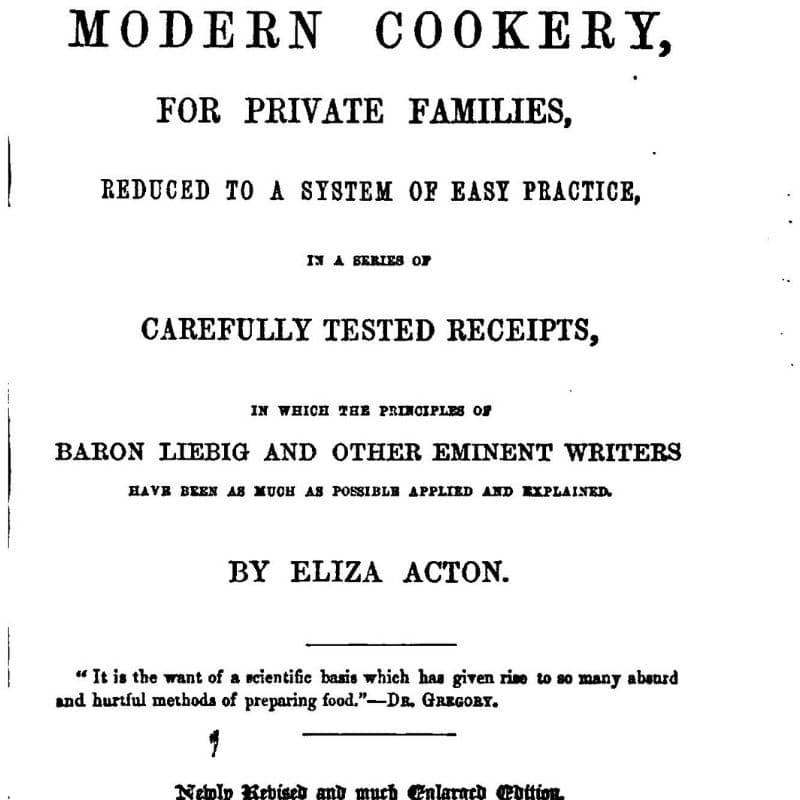

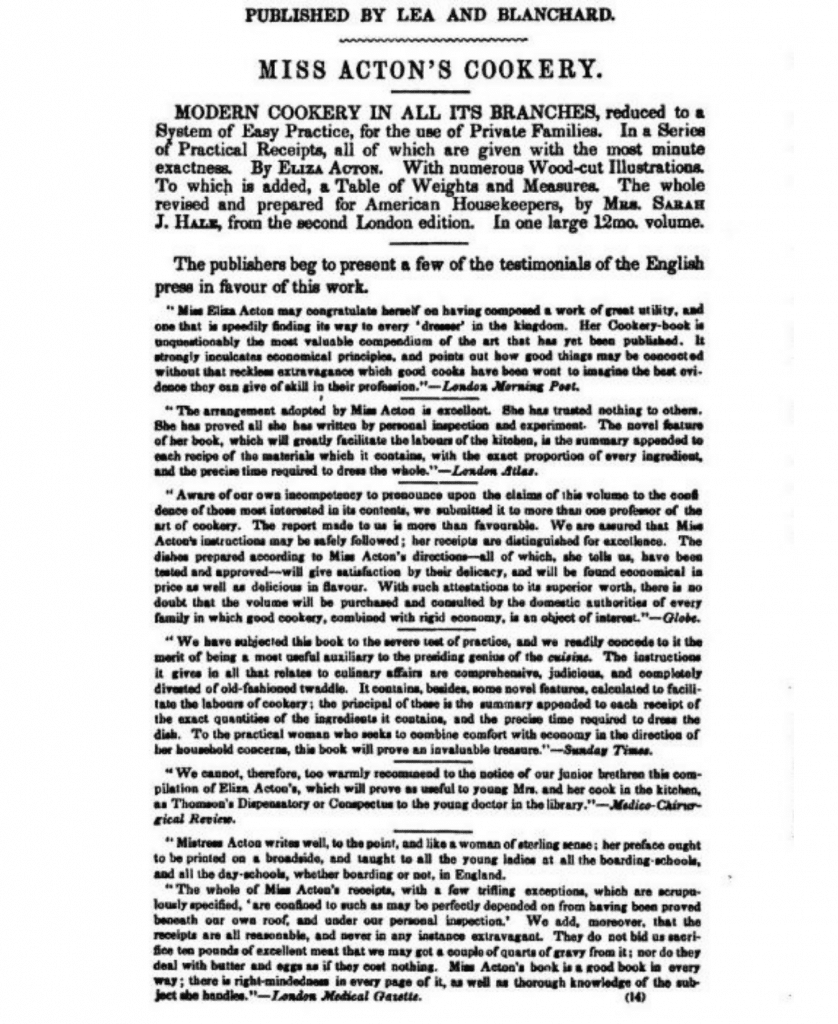

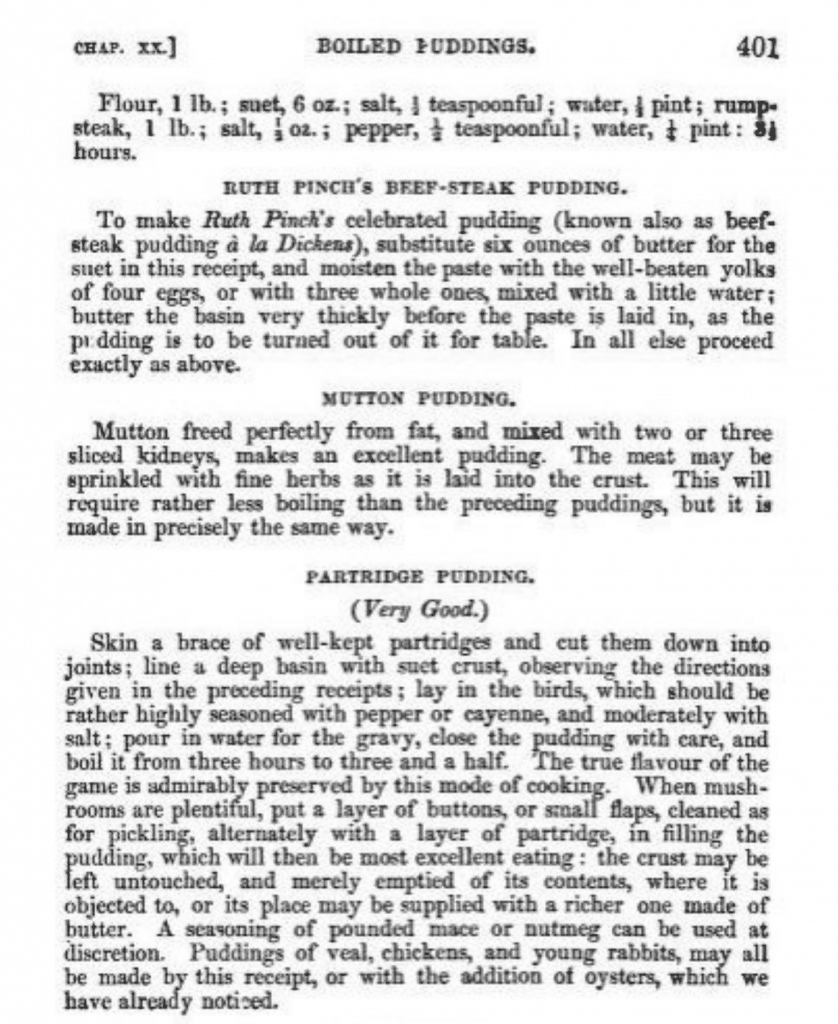

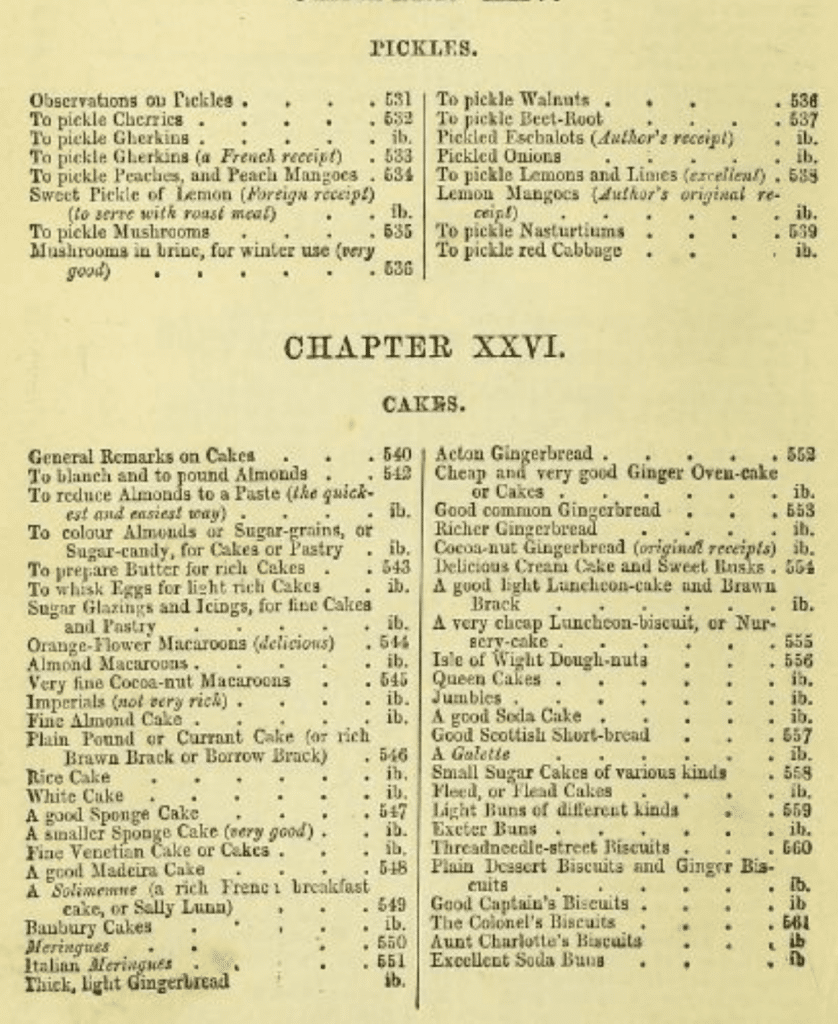

Poet Eliza Acton had a book of poems ready to go for her publisher. Eliza had a book of poems published via subscription already (you can read some of the poems of Eliza Acton here, free). Accounts differ, but some believe she was told that poetry didn’t sell and to spend her time on a cookbook instead. Eliza saw a lack of cookbooks geared toward non-professionals, and got to work. She spent ten years working on Modern Cookery for Private Families, Reduced to a System of Easy Practice in a Series of Carefully Tested Receipts in Which the Principles of Baron Liebig and Other Eminent Writers Have Been as Much as Possible Applied and Explained.

Modern Cookery is believed to be the first English cookbook to show ingredients in a block by themselves, after the recipe’s general instructions. (Listing them before the instructions, like the Dramatis Personae of a play, came still later.)

In earlier cookbooks you had to pick the ingredients out of the prose, hoping you hadn’t overlooked any—and concurrently hoping for some hint about quantities. Even “a handful” or “a pinch” is a quantity; “sufficient” or “a goodly amount” is not much help.

I would imagine that that one simple move, of reorganizing a common recipe format, would have caused quite a stir. She doesn’t include the ingredients separately in every recipe, but she is the first to do such a thing at all. I don’t necessarily see a reason why some recipes had the ingredient call-out, while others do not.

More Cookbook “Firsts”

There are other “firsts” in Eliza’s work too. It was the first time Christmas pudding, spaghetti, and Brussels sprouts appeared in a cookbook (at least an English cookbook). This was the first book written for people, and not servants or professional chefs or cooks.

It shows. It’s far easier to follow along with this cookbook and enjoy the writing. It isn’t as wordy as earlier cookbooks.

When Acton really loves something she does not gush but puts it in brackets, as if holding her emotions in. ‘Lemon Dumplings (Light and Good)’, for example. Or ‘Mushrooms Au Beurre (Delicious)’. It is this combination of honesty and reticence that makes her Eliza Acton (The Best).

Bee Wilson, Eliza Acton, my heroine, The Telegraph, May 8, 2011.

Those are the same sort of notes we see in cookbooks now. Someone pens in a word or two regarding a recipe, as a future reminder. Of course Eliza would consider her recipes to all be good and share-worthy, but she calls-out her favorites, and brings them to our attention.

On Entertaining

Eliza offered suggestions to help women throw those fancy dinner parties in order to pretend greater wealth, while maintaining “economy” in the days between to keep the household from becoming financially unstable.

The tension between economy and extravagance made visible by the different types of recipes that Acton includes in Modern Cookery was further highlighted by the ingredients used in each case. The idea of ‘household economy’ had was a mainstream concept by the time that Acton’s book was published–and the use of leftovers in meals played a key part in this. Acton’s recipes frequently demand the middle-class housewife religiously reuse whatever was left from previous dishes….

Sophie Hill, with Rachel Rich, Keeping up Appearances: Economy vs. Extravagance in Eliza Acton’s Modern Cookery, Hypotheses, June 28, 2016.

You can see how pound cake would have factored in here too. Eliza has a recipe for a “plain pound or currant cake.”

Some of the recipes are named for familiar things in Tonbridge, like a cake named for the street Acton lived on (Bordyke Veal Cake) and some referenced people she admired like Baron Liebig who wrote that bad cooking wasted food (Bavarian Brown Bread). She often gives generous credit for recipes that were given to her by others.

Deana Sydney, Eliza Acton’s “Saunders” Mashed Potato and Sausage Comfort Food, Lost Past Remembered, September 24, 2010.

Eliza included a recipe for Ruth Pinch’s Beef-Steak Pudding a la Dickens and includes a recipe for a Christmas Pudding in a nod to popular author (then as now), Charles Dickens. She sent a copy of her book to Charles Dickens in January 1845. He responded six months later with light praise for her work and an apology for his late response, as he had been in Italy.

Some sources say that Eliza and Charles began a regular correspondence, but I have been unable to validate that claim. Eliza did, however, have contact with plenty of known figures in her day, as you can see even from the credit she gives to others in her cookbook and from numerous letters she had written.

Eliza’s Book was Plagiarized

Franklin Habit, Published December 29, 2020.

As we know from the previous writers we have covered, not every cookbook author shared Eliza’s view on providing credit where credit was due.

Modern Cookery for Private Families was phenomenally popular, with every Victorian household owning a well-thumbed copy. It went through thirteen editions before being transplanted in the nation’s affections by new star on the block, Isabella Beeton with her Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management which freely plagiarised many of Acton’s recipes.

Louise Peskett, First Woman Eliza Acton, Writer of the First Cook Book Aimed at the Home Cook, Brighton Museums, Updated August 16, 2021.

Isabella Beecher, however, took the spotlight off Eliza. Between Isabella’s column for The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine (1857) and her book, Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management (1861), Beecher pilfered recipes from Eliza—and not just a few nor ONLY of Eliza’s work, but the books from other writers of the day. She built her fame on the hard work of other people.

Even though Eliza referenced the theft in her 1855 edition, it didn’t change Isabella’s popularity or the money Isabella was making. Unfortunately, Eliza Acton passed away in 1859.

For someone who was for some time a celebrity, why is it that none of her personal correspondence has survived? It would appear that of letters received by her, only four remain. It seems odd that she should have gone quite against the early nineteenth-century habit of keeping drafts of the letters she sent out as well as those she received, especially as these were often copied to send on to others. Was it that in the years between 1840 to her death in 1859, she received so much from admiring readers that she hadn’t room to store it all, or if the correspondent sent her a new recipe, she simply copied it to her files and destroyed the actual letter? But surely, she must have replied to those letters, so it seems strange that all these have been lost.

The Real Mrs. Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton by Sheila M. Hardy (2011), Page 13.

There is much we don’t know about Eliza Acton. We don’t know the details of what appears to be a failed love affair (and whether or not Eliza had a baby from that union). We don’t even know what Eliza looked like. Many older websites bemoan the lack of facts about Eliza, but that isn’t so much the case. We know more, thanks to the historian and author of an interesting book about Eliza Acton.

If you, like me, enjoy learning about famous food figures, I’d recommend turning to The Real Mrs. Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton by Sheila M. Hardy (2011).

Websites with Eliza Acton Recipes

To make it in this list, a website had to do more than just list the ingredients and directions of an Eliza Acton recipe. Bonus points if the website had more than one article using an Eliza recipe. If you, or a site you’ve discovered, has included recipes from Eliza Acton’s book Modern Cookery (or one of her other works), please do leave a mention in the comments section below. If it fits my criteria, I will add it in.

- Cupcake Project – Plum Pudding (True Historical Recipe)

- Duck and Roses – 168 Year Old Christmas Pudding – The Eating, 166 Year Old Christmas Pudding

- Finca Food – Christmassy Things – Part One – The Pudding

- History in the Making – To Mull Wine, Christmas Pudding, Macaroni a la Reine, Cocoa-Nut Gingerbread

- Jane Austen – Sally Lunn Buns or Solilemmes

- Katie’s Time Travelling Kitchen – Madeira Cake

- The Little Library Café – Coconut Cake. North and South.

- Lost Past Remembered – Eliza Acton’s “Saunders” Mashed Potato and Sausage Comfort Food

- Orchard Notes – Making Eliza Acton’s ‘Essex Pudding (Cheap and Good)’, The Norfolk Biffin, A History Part I – Biffin Desserts

- Sydney Living Museums – Dress to Impress (Eliza Acton’s English Sauce for Salad), Monday’s Pudding (Eliza’s ‘Good Daughter’s’ Mincemeat Pudding)

- Time to Cook Online – Coconut Gingerbread Cakes

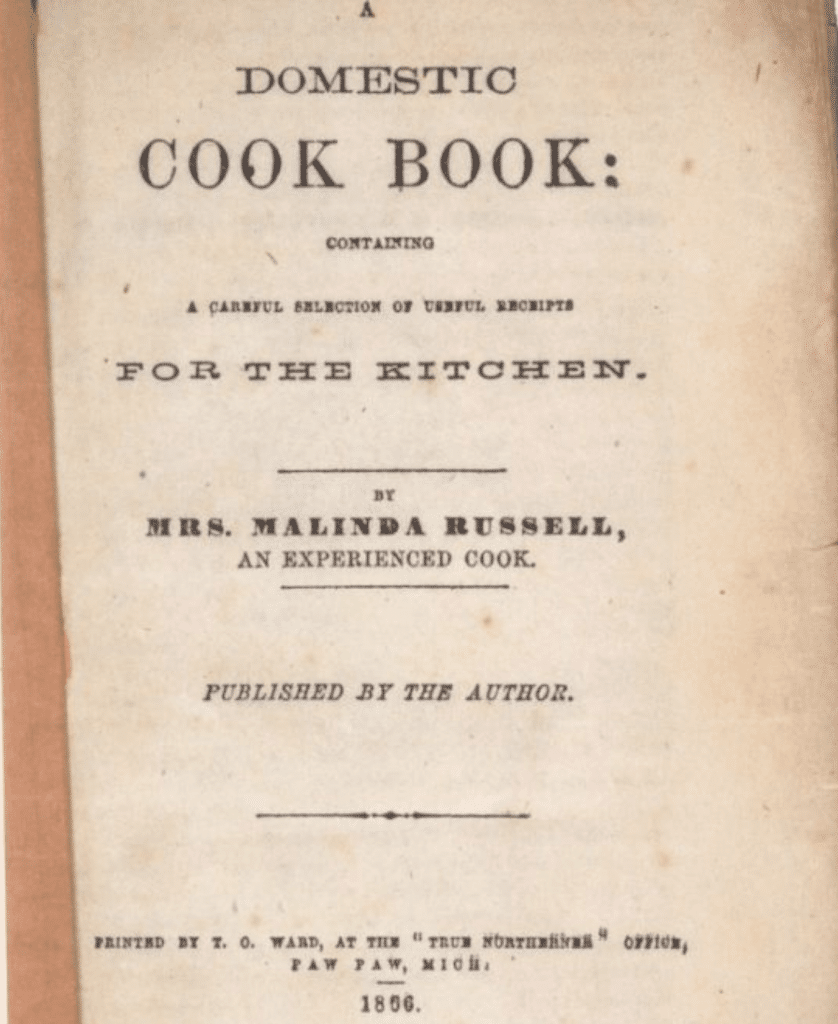

Malinda Russell: A Domestic Cook Book

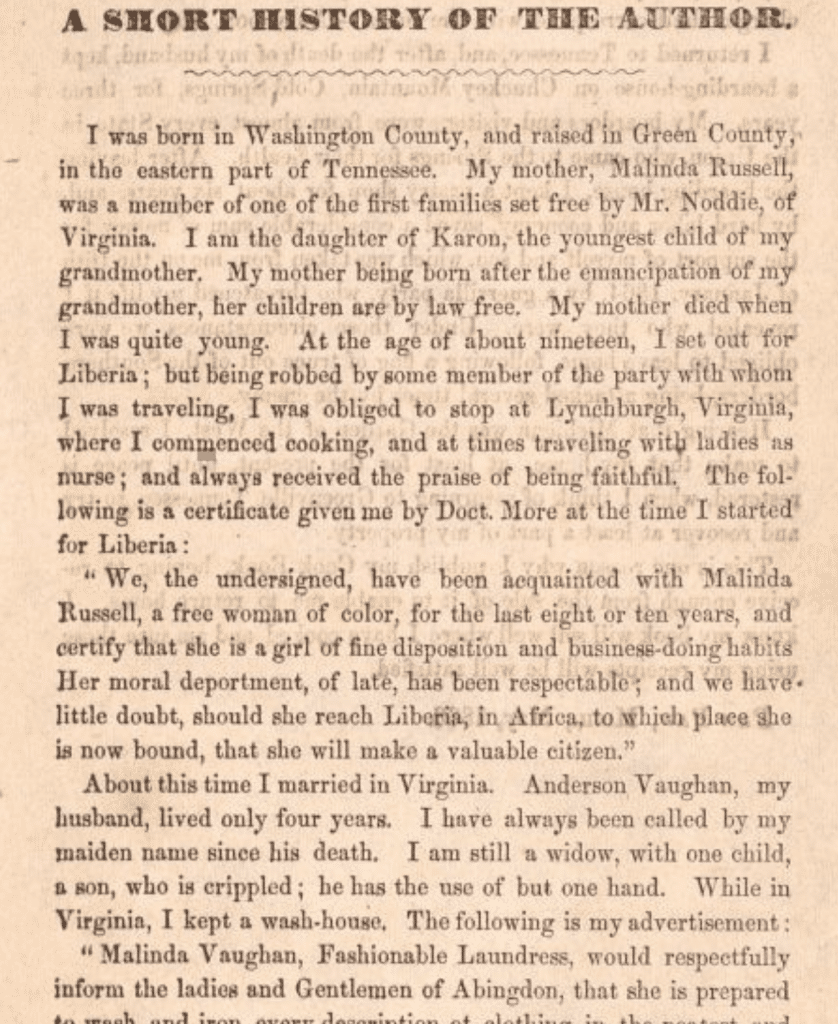

Malinda Russell published the first cookbook by a black woman in the US in 1866. It was by happy chance that a cookbook lover, Janice Bluestein Longone, rediscovered the little book. At the time, the rare books dealer had been digging through part of the collection of Helen Evans Brown, a California cookbook author and food writer. Malinda’s book was a the bottom of the box. Janice paid $600 for the only known copy of the book. It now has a home in the University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Research Center) as part of the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive.

Now, let’s meet Malinda.

Published in Paw Paw, Michigan in 1866, A Domestic Cook Book… is the oldest known cookbook authored by an African American. Found among the collection of California cookbook author and food writer Helen Evans Brown, this little book precedes Abby Fisher’s 1881 What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking by 15 years, making it a landmark in African American culinary and publishing history. However, it should be noted that two earlier household/hotel manuals by African Americans are known: The House Servant’s Directory (1827) by Robert Roberts and Hotel Keepers, Head Waiters and Housekeepers’ Guide (1848) by Tunis Campbell.

Julie McLoone, Now Online: The Oldest Known Cookbook Authored by an African American, University of Michigan Library Blogs, February 24, 2016.

No one knows much about Malinda Russell. What is known appears in her cookbook. So, we know she was born as a free woman, into a free family, in Tennessee in 1812. but when she was 19(ish), she planned to head to Liberia.

The Liberia part of the story should be understood alongside the broader history of the area. Greene County had been a center of abolitionist activity. From the early 1800s on, there had been notable emancipations in the county, including by the local Presbyterian ministers Hezekiah Balch and Samuel Doak, and Valentine Sevier, the county clerk. A Manumission Society had been organized there in 1815, and several others followed. Elihu Embree, a Quaker from adjacent Washington County, started the first abolitionist newspaper in Jonesborough in 1820.

At the same time, from about 1830 onward, Tennessee had enacted increasingly repressive laws restricting free blacks in the state. Thus, along with abolition, there were also colonization organizations, committed to sending free blacks to Liberia. Some whites saw colonization as a benevolent, protective act. Others, especially in west Tennessee, simply wanted free blacks to disappear, believing that their contacts with their enslaved counterparts would encourage escape and revolt.

The Tennessee Colonization Society, founded in 1850, was one of these groups. It has been estimated that from 1830 to 1860, around 700 blacks had been sent to Liberia thanks to the efforts of that group and others connected with Philip Lindsley.

It makes sense that Malinda may have understood that she was in a precarious position, and that may have prompted her to join a colonization party.

Think about that. You have no idea what to expect. You aren’t browsing the internet for information about Liberia or making calls to confirm the arrangements. You are relying on what you are hearing, and what you are hearing would definitely sound better than the current social situation. After Liberia was out of the picture, thanks to another theft, Malinda ended up in Lynchburg, Virginia.

Malinda’s Next Move

Malinda finds a job with a family, and learns to cook and bake. Malinda also meets a man, Anderson Vaughan, whom she marries. They have a son together. Four years later, she’s in another bind, because her husband dies (we don’t know of what), and leaves her alone with their son whom she describes as “crippled.” He only has the use of one hand. She heads back to Tennessee. There, she makes good use of her kitchen skills, opening a pastry shop and a boarding house, saving money over a span of six years. Malinda is threatened and robbed, and flees for Michigan.

We have no idea how her husband died, but we can grasp her desperation. Making her way across Union lines in the midst of the Civil War was incredibly dangerous. On her journey, Russell recounts being “attacked several times.” …Despite her free status, as woman of African descent, Russell’s civil rights were not recognized by U.S. courts. The 1857 Dred Scott decision confirmed that the protections and privileges of U.S. citizenship did not apply to Black Americans. The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act encouraged entrapment of freedmen and women without regard for their papers, like Solomon Northup in 12 Years A Slave.

Cherene Sherrard. What I Learned About a Pioneering Black Cookbook Author by Cooking Her Recipes, Atlas Obscura, November 20, 2020.

Think about the other authors we’ve explored. They didn’t typically include much information about themselves, at least, not anything not relevant to a cookbook. But Malinda gives us her life in a nutshell.

In her brief autobiography, this free woman of color tells us a great deal about herself…and surprising considering the post-Civil War tensions of the time. She was a hard-working, single mother, a business owner, and the ladies of the community esteemed her. Including their words of endorsement in her preface made good business sense, but we also can see the gesture as a measure of her integrity.

Russell acknowledged everyone responsible for her talent and her project – an unusual action in light of the out-and-out plagiarism that was common practice among her publishing contemporaries. She said she apprenticed under the tutelage of Fanny Steward, a colored cook of Virginia, that she followed “the plan of The Virginia House-Wife,” and attribution accompanied several of her prescriptions.

Another Mary Randolph Fan

Back to Mary Randolph we go! It’s interesting to note how popular Mary’s cookbook was, so much so that Malinda, who didn’t even live in the same state, knew of it. It’s not like they had online shopping back then. Malinda’s book isn’t a huge book, especially by today’s cookbook standards.

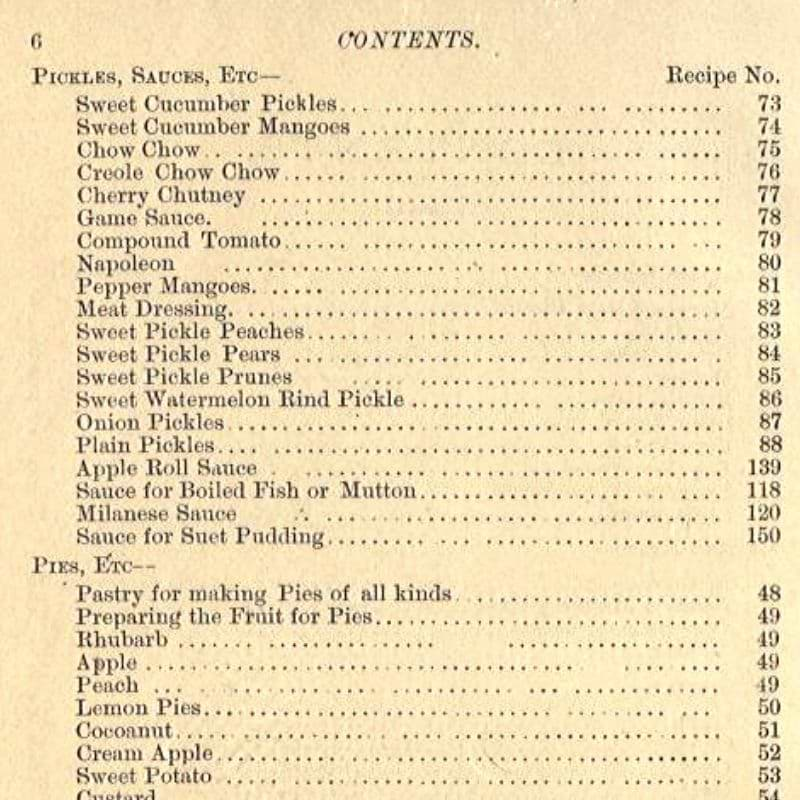

Russell’s book doesn’t have a table of contents or index and, aside from loosely grouping like receipts, a structure, but for all its 30 pages, she shares plenty of receipts. You’ll find cakes, cordials, pies, cookies, gelatin desserts, pickled and preserved fruits and vegetables, breads/rolls, and custards/puddings.

On the whole, there is an emphasis on sweet dishes and baked goods, but she finished with savory meat and poultry dishes, two fish recipes, and several handfuls of home remedies. Not one recipe has directions longer than about eight sentences (calf’s head soup and cream puffs are among the more complex, and all are written in paragraph form without a list of ingredients (characteristic of the era). Most are summed up in as little as 3-4 sentences (or less!), like Sally Lun:

Three tablespoons yeast, two do. butter, two do. sugar, two eggs, flour to make thick as cake. Let it rise six hours; bake quick.

“Do” in this case is the same as “ditto.” And, since you’ll need to know when we look at the pound cake recipe, a gill is an old form of measurement too. While a gill has varied depending on when and where the cook is located, it’s now considered half a cup (1/4 pint in Britain).

Malinda Russell’s (Stereotype Changing) Skills

The cookbook by Malinda Russell, with it’s large dessert section (makes me think Malinda was my kind of person!), and advanced skills highlight a different part of the Southern style of cooking and diet.

Mrs. Longone, long considered the top expert on old American cookbooks, knew immediately that she was holding the earliest cookbook by an African-American woman that had ever come to light. Turning the 39 fragile pages of the 1866 pamphlet, she realized, too, that it could challenge ingrained views about the cuisine of African-Americans.

Molly O’Neill, A 19th-Century Ghost Awakens to Redefine ‘Soul’, The New York Times, November 21, 2007.

Malinda’s book reveals the way a free woman cooked. It wasn’t traditional southern cooking either.

In terms of recipe development, one of the important cues…is her expertise in baking. This is important because, up to this point, we are being told that African-American women were not responsible for baking because that was where the intellect of cooking resided, because of its dependency on chemistry and the knowledge of leavening and all of the scientific variables — very much like the NFL used to say that Black men couldn’t be the quarterback.

A lot of that early writing misrepresented African-American knowledge in the sphere of baking, and [Russell] really does a terrific job undercutting that because she places so much emphasis on the baked goods that come out of her bakery. She identifies the fact that she’s an entrepreneur and has had not only a boarding house, but a bakery.

Monica Burton, Osayi Endolyn, and Toni Tipton-Martin, The Legacy of Malinda Russell, the First African-American Cookbook Author, MSN, February 23, 2021.

That’s one way to help change stereotypes. She’s not “survival cooking.” She’s not Southern cooking. Malinda is a pro and a business owner. She’s just cooking.

The Mystery of Malinda

Malinda wrote Domestic Cook Book: Containing a Careful Selection of Useful Receipts for the Kitchen to make enough money to return to Greeneville, Tennessee. Did she make enough profit to return? Did she find her way home again? We’ll never know.

The town of Paw Paw, Michigan’s library burned down, likely taking copies of her books with it. Another fire in the city around the same time likely took out a few more copies too. Malinda’s life thereafter is unknown. I hope we’ll find something, someday that will tell us more.

“Russell’s work was so important because it offered a glimpse into fine cooking by an African-American woman who’d never been a slave and whose skills and point of view went beyond what came to be called soul food. Her work challenged ingrained views of black cuisine and emerged following the black-liberation movement’s celebration of dishes harking back to Africa.”

Robin Watson, 1866 African-American Cookbook from Michigan Woman Offers Voice from the Past, Detroit News, February 21, 2020.

Wow, what a life! While I don’t see copies of the original book available in facsimile like the rest, I think you’ll be more than pleased with the substitution I discovered below (they both include Malinda):

Websites with Malinda Russell Recipes

Recipes from Malinda Russell are also in use today. Take a look at the websites below and see what other folks are cookin’ up. If I missed you, please do let me know.

- Chenée Today – Lemon Sour Cream Pound Cake + Juneteenth Cookout 2021

- Cooking is My Sport – Malinda Russell’s Washington Cake

- History Dollop – Raspberry Tea Cake, 1866

- The Jemima Code – First African-American Authors: Celebrity Chefs Part II

- Malinda Russell – Modernized Recipes

- NPR Kitchen Window – A Meal To Honor Early African-American Cookbook Authors (Malinda Russell’s Allspice Cake)

- She Cooks with Kids – Best Laid Plans (Malinda Russell’s Cream Cake)

If you chose to use the original, unaltered recipes in Malinda’s cookbook, you might find this link helpful: Malinda Russell Recipe Testing: Conversion Table.

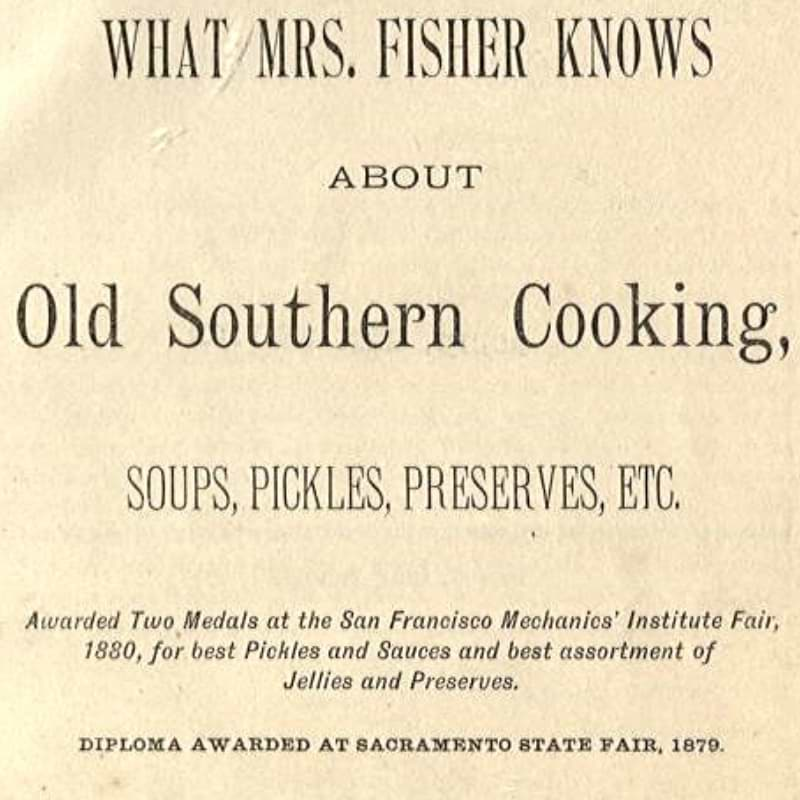

What Mrs. Fisher Knows about Southern Cooking

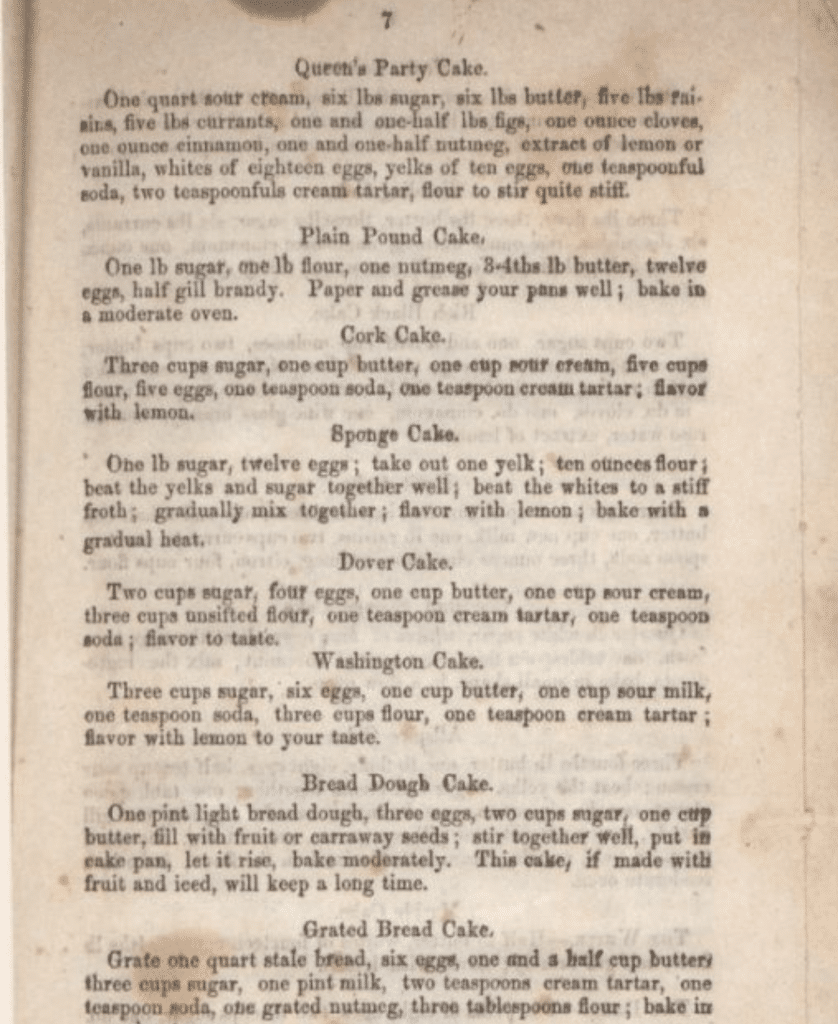

When I first “cracked open” the digital version of Abby Clifton Fisher’s cookbook, Familiar recipes like Sally Lunn bread, chicken salad, and Charlotte Russe flooded the page. I guess we consider some foods a classic for a reason—they are beloved and timeless. Good food and good recipes get passed along. So of course here, too, we find not just one, but two recipes for pound cake.

It’s a book that was almost lost to time. Karen Hess is behind the 1995 reprinting of the book, but it didn’t happen overnight, as she shares below:

Hess is an expert in historical Southern cooking and one of the few people who had glimpsed Fisher’s cookbook when it came up for auction at Sotheby’s in New York in 1984. Shortly afterward, she mentioned the volume to Phil Zuckerman of Applewood Books, a small Massachusetts firm that publishes historical facsimile books. “She told me it would be a fabulous book to do if we could find a copy of it,” recalls Zuckerman.

It took several years, but in 1994 Zuckerman finally called Hess. He had tracked down a limited-edition copy of the book that had been published in Connecticut. Applewood would reprint it, and he wanted Hess to write the historical afterword.

Candy Sagon, Rediscovering the First Black Cookbook, The Washington Post, November 29, 1995.

What Mrs. Fisher Knows was originally believed to be the oldest book written by an African-American woman until the discovery of Malinda Russell’s book (above). Abby Fisher had a different kind of life experience than Malinda Russell. For starters, Abby was born a slave in South Carolina, around 1831 to Abbie Clifton, an enslaved woman, and white farmer Andrew James.

What We Know of Abby Fisher

Abby doesn’t stay in South Carolina and instead moved to Mobile, Alabama. In the 1850s she marries Alexander Fisher. After Emancipation, they leave again. The U.S. Census of 1880 provided helpful facts about Abby Fisher and her family.

The census listed Fisher’s name, age (then 48) and a San Francisco address. Her profession was listed as “cook” and under the heading of race was the notation “mu.,” or mulatto. The census records also noted that her mother was from South Carolina and her father from France….

How the Fishers made the trek to San Francisco from Alabama, where three of their children were born, remains a mystery, Hess admits. The transcontinental railroad had been completed by then, but such a journey would have been costly.” Her last child was born in Missouri, a popular jumping-off place for going west. It’s not inconceivable that she was part of a wagon train, maybe even as a cook,” she muses.

The fact that Fisher and her family did make it to San Francisco indicates several things to historians, adds Hess. “There was a much larger African-American presence in the West than many realize. San Francisco was a bustling city, but with a lot of the frontier spirit. Maybe {African Americans} there were not discriminated against as much.”

Abby’s entry included “Mrs. Abby Fisher & Co.,” along with the notation, “pickles, preserves, brandies, fruits, etc.”

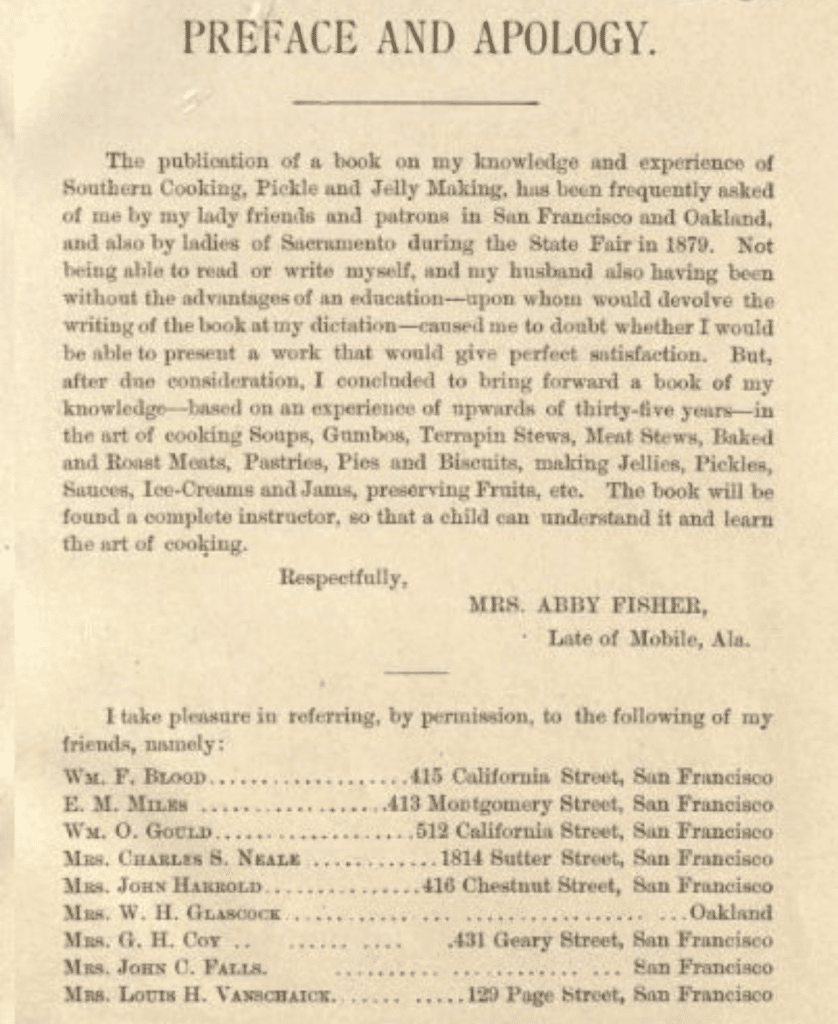

The only thing we know about Abby is what she tells us in the preface and apology (her words) in her cookbook. She begins with stating why she wrote a cookbook with 160 recipes: because her “lady friends and patrons” in San Francisco and Oakland, and the “ladies of Sacramento during the State Fair in 1879,” asked her for help.

The State Fair? What?

On the front page, Abby shared that she was awarded a diploma at the Sacramento State Fair of 1879. It’s a huge, enormous, big deal. It is their highest award. A year later, Abby received two medals at the San Francisco Mechanics Institute Fair 1880 for the best pickles and sauces, and assortment of jellies and preserves. Abby reveals how she is known for her “knowledge and experience of Southern Cooking, Pickle, and Jelly Making.”

Abby reveals how she and her husband lack education and cannot read or write. So, she had a little help from her friends.

“The publication of a book on my knowledge and experience of Southern Cooking, Pickle and Jelly Making, has been frequently asked of me by my lady friends and patrons in San Francisco and Oakland, and also by ladies of Sacramento during the State Fair in 1879. Not being able to read or write myself, and my husband also having been without the advantages of an education—upon whom would devolve the writing of the book at my dictation—caused me to doubt whether I would be able to present a work that would give perfect satisfaction. But, after due consideration, I concluded to bring forward a book of my knowledge—based on an experience of upwards of thirty-five years—in the art of cooking Soups, Gumbos, Terrapin Stews, Meat Stews, Baked and Roast Meats, Pastries, Pies and Biscuits, making Jellies, Pickles, Sauces, Ice-Creams and Jams, preserving Fruits, etc. The book will be found a complete instructor, so that a child can understand it and learn the art of cooking.”

Abby Fisher, What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Cooking (1881).

I love that. Abby is humble, yet confident in her skills. She isn’t interested in showing off, but in creating a book that’s useful for someone of any age.

Fisher dictates her recipes to her female friends among San Francisco’s social elite. What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking is published in 1881 by the Women’s Co-operative Printing Union of San Francisco, an entity fostered by suffragist and publisher Emily Pitts Stevens.

Kimberly Brown, Mrs. Fisher Pens a Cookbook, California State Library, Accessed November 12, 2021.

Words are Hard

Do you remember playing “Chinese telephone” as a kid? Or even, “tell your teen something and then ask him to repeat it back?” That’s a fun game too, with similar results to those of the same game with husbands. Abby’s southern accent and unusual dishes (like jambalaya) proved too tricky for some of her helpers.

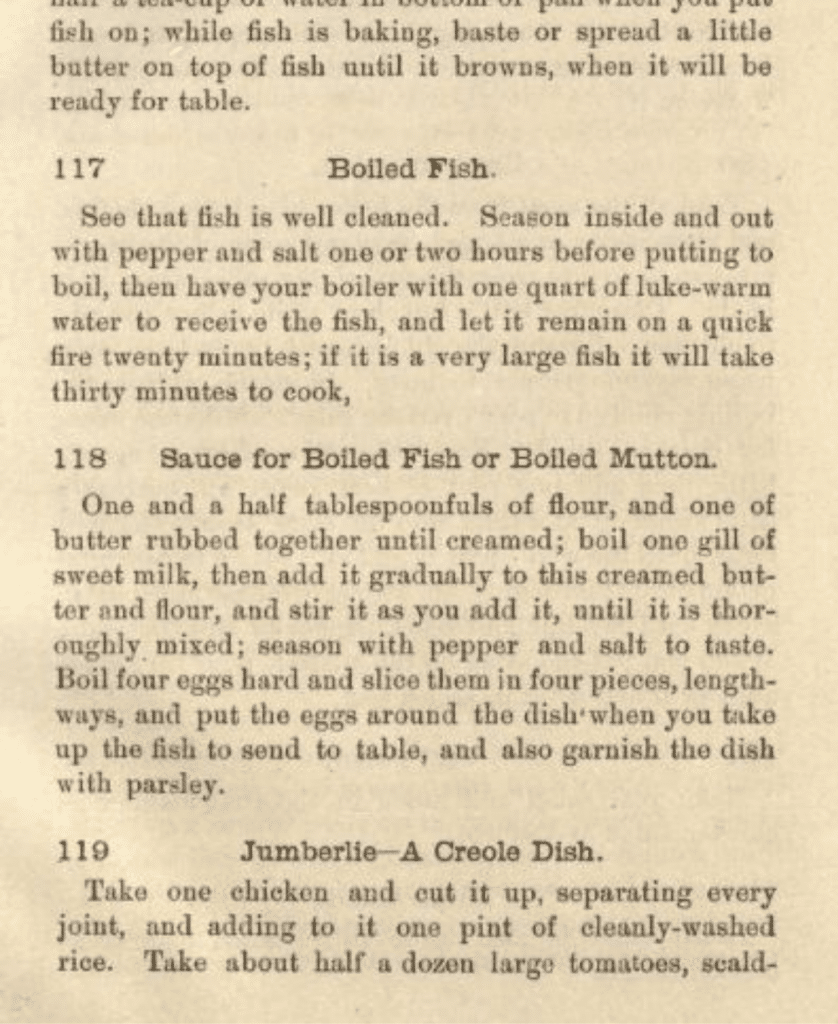

The dictation, however, was not without its flaws. Some of those assisting Fisher in writing and compiling her recipes either struggled with her Southern accent, or simply had never heard of the dishes. (Eight of her assistants were from San Francisco, one was based in Oakland.) As such, there are a few quirks in the text that stand as proof of the difficulty of the task Fisher and her transcribers faced. Succotash is referred to as “Circuit Hash.” Jambalaya is called “Jumberlie.” And mayonnaise is listed as “Milanese Sauce.”

Rae Alexandra, The Formerly Enslaved Cook Who Became a Celebrity Chef in San Francisco, February 25 (year not provided).

Because of the fire that followed the 1906 earthquake, most copies of the book were lost, making it extremely rare; a copy sold this year at a New York auction for $11,000. Imagine my surprise when I looked at a 19th-century census recently and discovered Fisher lived a block from my store, Omnivore Books on Food. The reality that she likely shopped at my store (a butcher shop back then) sent chills up my neck. Perhaps she even sold her preserves at the front of the shop, which was then a grocery store (and is now my pet supply store, Noe Valley Pet Company). The house looms large on the north side of the block, with many original Victorian details. In fact, a local resident recalls his mother leaning over the back fence and gossiping with Tillie, Abby Fisher’s youngest daughter, after she inherited the house from her parents.

Celia Sack, The Bookmongers Book Review: What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, Edible San Francisco, by Abby Fisher, July 22, 2017.

By the 1890s, Abby’s husband had become a porter, while she ran her pickle and preserve business solo. “According to the U.S. Census of 1900, the Fishers were both able to read and write. They also owned their home outright at 440 Twenty-Seventh Street west of San Francisco Bay in scenic foothills,” shares the Racing Nellie Bly website.

That’s the last we know of Abby Fisher and her family. we don’t know if they came out of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake okay. Many sources believe the earthquake and resulting fires are the reason why so few copies of her book remain. How amazing is it that we still have pieces of her life, thanks in no small part to the details she provides in an introductory paragraph?

Websites with Abby Fisher Recipes

- Disney Parks Blog – Historic Peach Cobbler Recipe Honors Black History Month at Epcot

- Half-Baked Harvest – Southern Double Crusted Cinnamon Sugar Peach Cobbler

- Historical Foodways – Mrs. Fisher’s “Plantation Corn Bread or Hoe Cake,” Or A Brief Introduction to a Real-Life Black Female Food Figure You Should Know About (Plantation Corn Bread or Hoe Cake)

- Linguina – Abby Fisher’s Sweet Potato Pie

- Marlene Dulery Food Stylist – Sweet potato pie from Abby Fisher, 1881

- NPR Kitchen Window – A Meal To Honor Early African-American Cookbook Authors (Abby Fisher’s Chow Chow)

- Okra Magazine – What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking: Crab Croquettes

- Parnell the Chef – Southern Sweet Potato Pie Recipe (Soul Food)

- PBs Parents Kitchen Explorers – Abby Fisher’s Corn Egg Bread

Pound Cakes in History

Isn’t it interesting how all of these different people, from different backgrounds, included at least one recipe for a pound cake? It didn’t matter if the writer were “a lady” or someone who couldn’t read or write, someone who came from wealth, or someone who kept starting from scratch. The love of a good pound cake is universal.

.

.

Leave a Reply